Commentary

War films made during World War II are now often called propaganda films. It’s true that, for the duration of the war, Hollywood worked in conjunction with the war department to ensure that American movies were aiding the war effort, not hindering it. However, this negative label implies that the purpose of these films was simply to manipulate people. While some war movies did alter historical facts, the majority had no bigger purpose than to boost morale.

Today’s moment of movie wisdom is from “Destination, Tokyo” (1943). The scene takes place 59 minutes into this 135-minute film. The crew of an American submarine is mourning the death of a beloved shipmate. The captain (Cary Grant) recalls his deep friendship with the deceased and remembers seeing how proud he was to give his 5-year-old child a pair of roller-skates. He explains that the Japanese soldier who killed him was given a dagger at 5 years old. The crew is deeply moved by his conclusion that their friend would have been happy to die in the fight against a system which trains children to be killers.

In the film, Captain Cassidy (Grant) is commanding the submarine USS Copperfin on a secret mission during World War II. When he opens the sealed orders at sea, he learns that their job is to rendezvous with a PBY Catalina at the Aleutian Islands and pick up meteorologist Lt. Raymond (John Ridgely). After that, their destination is Tokyo Bay, where Raymond will help the American Armed Forces prepare for the Doolittle Raid by obtaining important weather information. Once they have picked up Raymond, the Copperfin is attacked by two Japanese seaplanes, and their attempt to rescue a survivor leads to the death of a crewmember.

Nearing Tokyo Bay, the Copperfin encounters many hazards, including anti-torpedo nets and minefields. The crew is a resourceful group of men and an interesting collection of characters. There’s Wolf (John Garfield), a cocky ladies’ man; Tin Can (Dane Clark), a Greek-American with a chip on his shoulder because of familial tragedy; Cookie (Alan Hale, Sr.), the jovial cook; Pills (William Prince), a pharmacist’s mate who has to perform surgery in an emergency; and of course the wise captain. These men have to band together to survive the trials they encounter during their difficult mission.

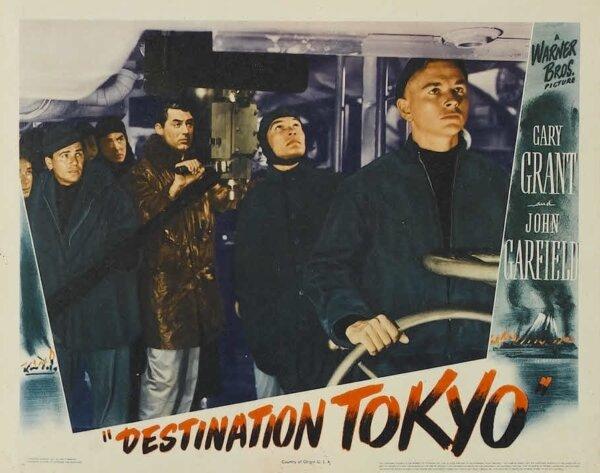

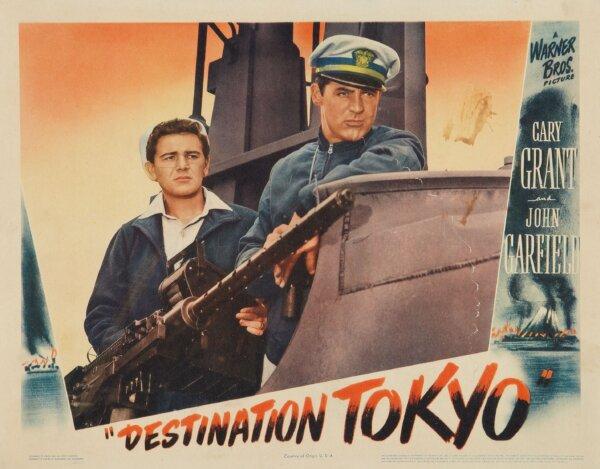

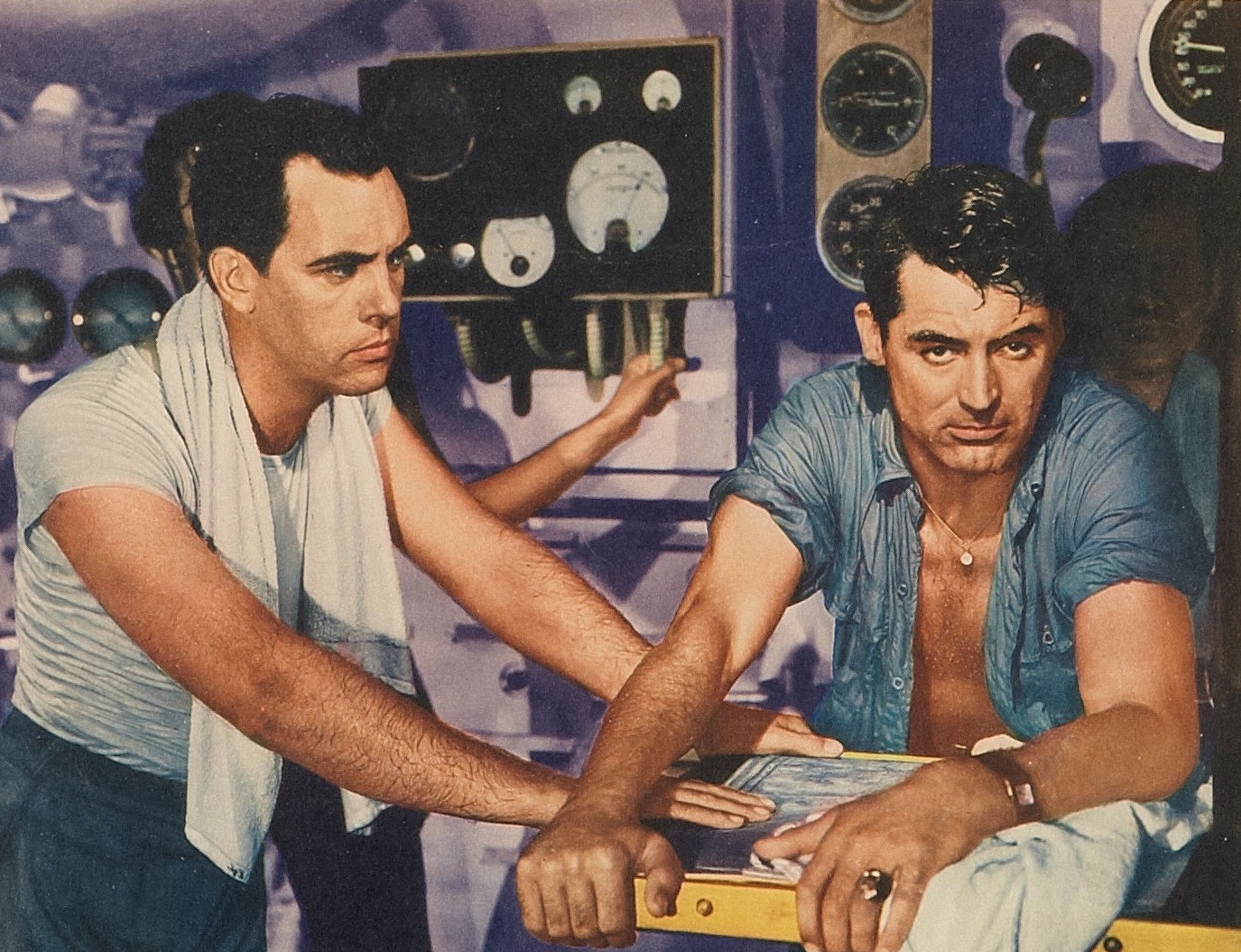

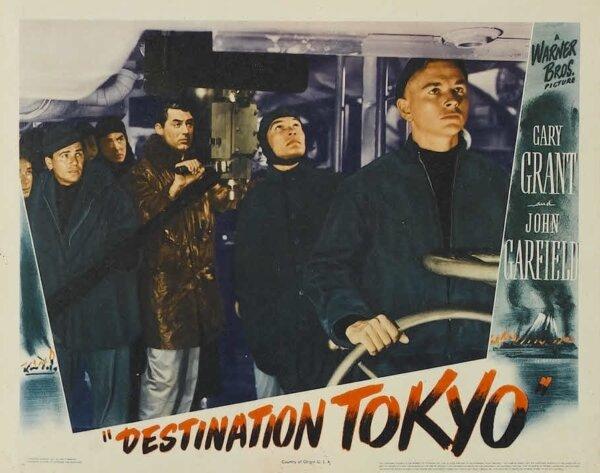

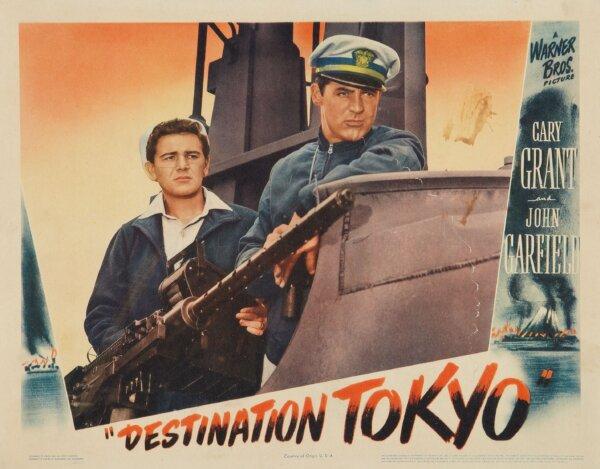

Lobby card from the 1943 film “Destination, Tokyo.” (MovieStillsDB)

The Scene

When the Copperfin is attacked by two Japanese planes, the American ship goes to pick up the enemy pilot who survived. Torpedo man Mike (Tom Tully) is stabbed to death when tries to pull the survivor aboard. The crew mourns his death as he is buried at sea. The other men wonder why Tin Can was absent from the funeral, and he explosively describes the murder of his uncle, explaining that he couldn’t bear the extra grief of attending Mike’s funeral too. Captain Cassidy walks into the impassioned scene and asks whether the men are “trying to figure out about Mike.” He says that the officers and crew of a submarine are closer than most other groups of men in the navy. Mike was with Captain Cassidy on his first patrol, and he was his good friend.

The captain goes on to say that he knew Mike’s family, his fine-hearted wife and his beloved children. He recalls the time Mike proudly purchased the finest roller-skates money could buy for his 5-year-old son. “Roller-skates for a 5-year-old,” he reiterates, and then adds, “Well, that Jap got a present, too, when he was 5, but it was a dagger. You see, his old man gave him a dagger so he’d know right off what he was supposed to be in life. ... There are lots of Mikes dying right now. And a lot more Mikes will die, until we wipe out a system that puts daggers in the hands of 5-year-old children.”

Its Significance

Mike’s death is one of the saddest moments in the film. It affects all the crew members deeply, and time is taken to show each man’s reaction to the tragedy. New recruit Tommy Adams (Robert Hutton) is especially devastated by Mike’s death because he believes he could have prevented it. He ended up shooting the man who stabbed Mike, but he feels responsible for not acting faster. After that, the Copperfin enters the most difficult part of its mission. The whole crew is deeply motivated to perform their job successfully so that Mike and all their other fallen Allied comrades won’t have died in vain.

As most war movies show, the hectic violence of wartime can become a mindless business of killing. However, moments of death and tragedy like this remind everyone of our individual humanity. After losing their friend when trying to be merciful to an enemy soldier, all the men are silently questioning why they are fighting the war at all. To remind his crew of the importance of the fight, the captain concludes, “You know, if Mike were here to put it into words right now, that’s just about what he died for: more roller-skates in this world, including some for the next generation of Japanese kids. Because that’s the kind of a man Mike was.” Americans back home who were missing and mourning their loved ones in the military appreciated this message about why we were fighting as much as servicemen, if not more.

Lobby card from the 1943 film “Destination, Tokyo.” (MovieStillsDB)

Training for Patriotism

“Destination Tokyo” was based on many real-life military events. The production used Captain Dudley Walker Morton and crewmember Andy Lennox of the USS Wahoo as technical advisors, and the cast spent time at the Mare Island Naval Shipyard to familiarize themselves with submarine operations. The submarine set used for the Copperfin was modeled on a real submarine. To keep the film from being helpful to the enemy, however, they equipped it with apparatus from multiple types of subs. However, the finished film was still accurate enough that the Navy was able to use the film as a training tool for submariners.

War films would sometimes dehumanize the enemy to make it easier to justify their killing. This was especially common with the Japanese, since they often seemed so much more foreign to the average American than the Germans. However, this scene in “Destination Tokyo” was a stirring reminder that our enemies were also human and not individually evil; at the time, they may have been trained for violence since a young age. We could become slaves to a similar evil plan if we blindly follow a human leader without questioning his actions against a higher standard of right and wrong.