Risk Factors

Anyone can contract Lyme disease, but certain factors increase the likelihood of infection. These include where you live, how much time you spend outdoors, and even lifestyle influences that affect immune health.

- Location: Living in or frequently visiting areas where Lyme disease is common. More than 90 percent of U.S. cases occur in the Northeast from Maine to Virginia, the upper Midwest (Wisconsin, Minnesota, Michigan), and the West Coast, mainly northern California and Oregon. Cases have also been reported across 49 U.S. states and parts of Europe and Asia.

- Time of year: Spending time outdoors between April and October, especially in tall grass, brush, shrubs, or wooded areas in tick-infested regions.

- Certain occupations: Working outdoors in jobs such as landscaping, farming, forestry, construction, railroad maintenance, oil field work, or park services.

- Mold exposure: Experiencing mold-related illness, which may weaken the immune system and make people more susceptible to Lyme disease.

- Pets: Owning pets or livestock that can bring ticks indoors

- Age: Children ages 5 to 14 and adults over 65 face the highest risk of contracting Lyme disease.

Bioweaponry Controversy

The origin of Lyme disease has been the subject of debate, with some claiming it may have ties to bioweapons research. This theory stems from an interview attributed to Willy Burgdorfer, the scientist who discovered the Lyme bacterium and had investigated an organism used in biological weapons programs during the same period as the Lyme outbreak. The claim was detailed in Kris Newby’s book, “Bitten: The Secret History of Lyme Disease and Biological Weapons.”

1. Early Localized Stage

In about 75 percent of cases, a red, raised spot called erythema migrans appears 3 to 30 days after a tick bite (on average, about seven days). It often develops on the thigh, buttock, trunk, or armpit and can expand up to 20 inches, sometimes clearing in the center. The rash may itch, feel warm, or cause no sensation at all. In some cases, it fades and then reappears weeks later. It may look different in different people, including:

- Bull’s-eye rash: Resembling a target or bull’s-eye pattern, this is considered the most characteristic sign of Lyme disease. However, it occurs in only about 19 percent of erythema migrans cases.

- Circular or oval-shaped rash: Gradually expanding around the site of the tick bite.

- Unnoticeable rash: Going unnoticed, particularly on dark skin or in areas of the body that are hard to see.

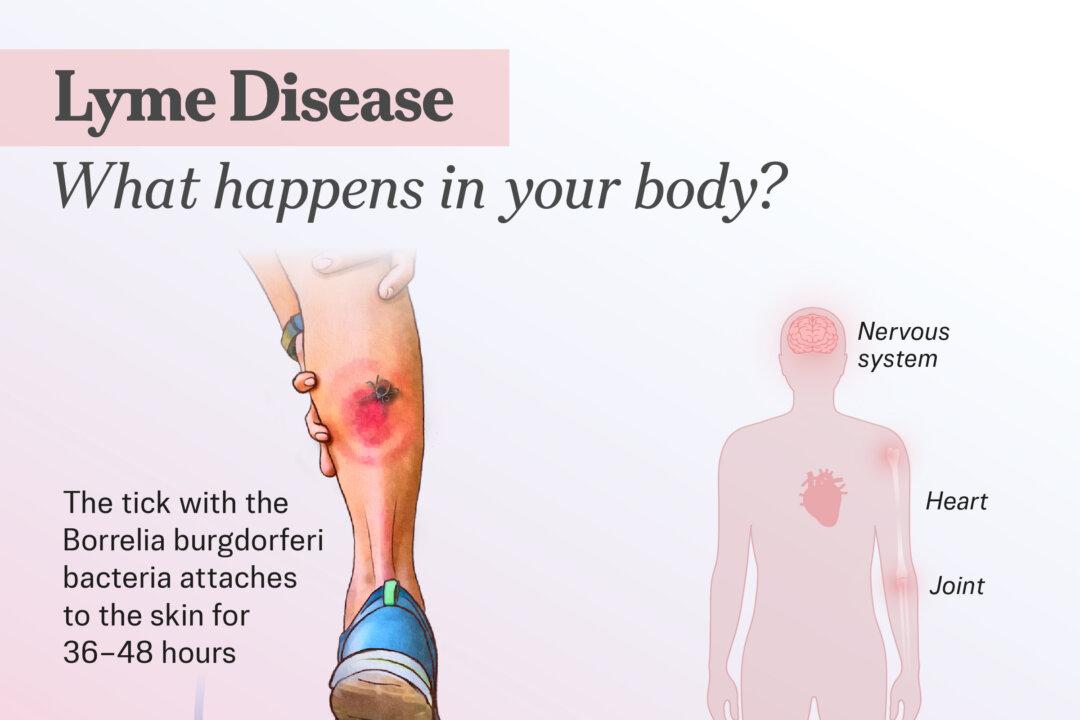

2. Disseminated Stage

This stage begins days to weeks after the initial rash, as the bacteria spread throughout the body. Symptoms may include:

- Flu-like symptoms: Fever, chills, fatigue, headache, muscle aches, and stiff neck.

- Other early signs: Swollen lymph nodes, sore throat, and general discomfort.

- Additional rashes: In nearly 50 percent of untreated cases, more—usually smaller—erythema migrans spots may appear elsewhere on the body.

- Neurological or heart issues: About 15 percent of people with Lyme disease experience nervous system issues, such as meningitis, Bell’s palsy (temporary weakness or paralysis of facial muscles), nerve pain, or limb weakness. Up to 8 percent develop heart problems, such as heart block, myocarditis (inflammation of the heart muscle), pericarditis (inflammation of the lining around the heart), and arrhythmia (irregular heartbeat).

3. Late Stage

If left untreated, the infection can lead to complications months to years later, such as:

- Blood tests: The most common method uses a two-step blood process. An ELISA test detects antibodies against Lyme disease, but can produce false negatives. If needed, a second ELISA or a Western blot (a test that identifies specific proteins) confirms the diagnosis, especially in later stages.

- ImmunoBlot: The IGeneX Lyme ImmunoBlot detects antibodies to several types of Lyme-causing bacteria.

- Lumbar puncture: A spinal tap may be used to obtain cerebrospinal fluid (which surrounds the brain and spinal cord) or joint fluid if the infection has spread.

- PCR testing: Polymerase chain reaction testing identifies fragments of Borrelia burgdorferi’s genetic material for a quicker diagnosis.

- Neuroimaging tests: PET scans (which measure brain activity using a radioactive tracer), functional MRI (which maps brain activity by measuring blood flow), and diffusion tensor imaging (which shows connections between brain cells) may detect brain fog, a common neurological symptom of Lyme disease.

Immediate Response to Tick Bite

If you are bitten by a tick, remove it immediately using clean tweezers or a tick removal tool. Grasp the head close to the skin and pull upward gently, without twisting or crushing the tick. Avoid using irritants like petroleum jelly or heat, which can increase the risk of infection.

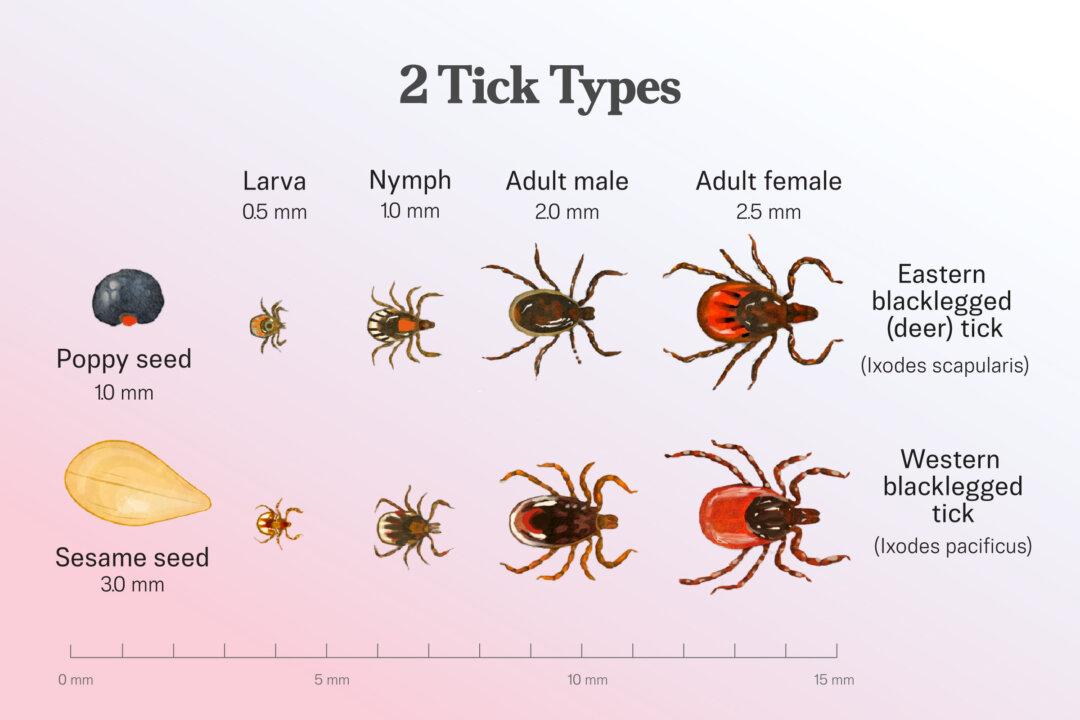

1. Asymptomatic Patients With Tick Exposure

A single dose of the antibiotic doxycycline may be given as a preventive measure to both children and adults who have been bitten by a tick. This is recommended if the tick is a species capable of carrying Lyme disease, was attached for at least 36 hours, and can be removed within 72 hours of starting treatment.

2. Erythema Migrans Rash

Patients who develop one or more classic erythema migrans rashes in an area where Lyme disease is common should begin treatment without further diagnostic testing. Recommended treatment includes a 10-day course of doxycycline or a 14-day course of amoxicillin or cefuroxime axetil. For patients who are allergic or intolerant to these medications, a 5- to 10-day course of azithromycin may be used as a second-line option.

3. Neurologic Manifestations

For patients with neurologic symptoms, intravenous antibiotics such as ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, or penicillin G are recommended. In some cases, oral doxycycline may also be an option. The recommended duration of treatment is 14 to 21 days.

4. Cardiac Manifestations

In cases of Lyme-associated heart problems with mild symptoms, oral doxycycline may be sufficient. However, patients with more severe cardiac symptoms, such as symptomatic heart block, may require hospitalization. In these cases, intravenous ceftriaxone is the preferred treatment, and a temporary pacemaker may be used instead of a permanent one, as Lyme-related heart block is usually reversible with antibiotics. Once the patient’s condition improves, treatment can be transitioned from intravenous to oral antibiotics for a total duration of 14 to 21 days.

Alternative Treatments

While antibiotics remain the standard treatment for Lyme disease, some people explore alternative or complementary therapies to relieve lingering symptoms or improve quality of life.

- Variable frequency electromagnetic energy (VFEM) therapy: A 2024 study reported that after 10 VFEM treatments, all eight patients with post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome showed improvement and were able to resume work or daily activities with better functional capacity.

- Acupuncture: Acupuncture treatment may help alleviate Lyme-related symptoms such as migraines and joint pain.

- Ozone therapy: Ozone therapy, which uses a form of oxygen in gas or liquid form, is commonly administered intravenously to treat infections and disinfect wounds. It is considered versatile and may target pathogens such as Borrelia burgdorferi. It may be used alone or alongside other treatments. Some reports suggest highly favorable responses, including one case study in which a patient fully recovered after receiving ozone therapy without antibiotics. However, more research is needed to confirm its effectiveness.

- Apitherapy: A small study published in February suggested that bee-sting therapy—one to 15 stings every other day, totaling 102 stings—reduced or eliminated spine and joint pain in patients with Lyme arthritis, a late-stage complication of Lyme disease. The study also reported possible antibacterial benefits lasting up to two years. However, the findings were limited, and apitherapy carries serious risks, including severe allergic reactions such as life-threatening anaphylaxis. It is not a safe at-home treatment and should not be attempted without medical supervision.

1. Nutritional Supplements

Key supplements include magnesium for energy and immune support, N-acetylcysteine to boost glutathione production, and sulforaphane from cruciferous vegetables to help reduce brain inflammation. Vitamin B12 and DHA omega-3 fatty acids may also aid neurological healing and cognitive function.

2. Anti-Inflammatory Diet

Anti-inflammatory nutrition forms the foundation of natural Lyme management. Whole foods rich in antioxidants—such as wild-caught fish, colorful vegetables, berries, and healthy fats—should be emphasized, while processed foods, refined sugars, and unhealthy oils are best avoided.

3. Gut Health Support

Supporting gut health is also crucial, as much of the immune system is rooted in the gastrointestinal tract, where nutrient absorption and microbiome balance play key roles in overall immunity. A 2020 study found that people with chronic Lyme disease had a distinct gut microbiome, marked by increased Blautia and decreased Bacteroides. While similar changes may also occur with antibiotic use and other conditions, these findings suggest that addressing the microbiome may be an important part of care.

4. Detoxification Support

Environmental toxins such as heavy metals, plastics, volatile organic compounds, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, pesticides, mold, and formaldehyde can impair the immune and nervous systems, potentially worsening Lyme disease symptoms.

5. Moderate Exercise

Moderate exercise may benefit people with Lyme disease by stimulating muscles, nerves, circulation, and lymph flow. It may also help move hidden bacteria into the bloodstream, where the immune system can target them. However, overexertion should be avoided.

1. Avoid Tick Exposure

Reducing your time in tick-prone areas and taking precautions outdoors can lower the risk of tick bites.

- Avoid wooded areas, tall grass, leaf piles, and brush.

- Stay in the center of trails and avoid sitting on the ground or stone walls.

- Maintain your yard by trimming trees and shrubs to increase sunlight, since ticks prefer shade. Create a yard-wide barrier of wood chips, mulch, or gravel between your lawn and wooded areas to prevent tick migration. Seal openings in stone walls to keep out tick-carrying animals, and place outdoor living spaces in sunny, mulched areas where ticks are less likely to survive.

- Wear protective clothing, such as long sleeves, long pants tucked into socks, enclosed shoes, and light-colored fabrics that make ticks easier to spot.

- Keep long hair tied back, and use protective netting on strollers and playpens.

- Check your skin, clothes, and pets for ticks after being outdoors.

2. Repel Ticks

Using repellents correctly is another important way to reduce the risk of infection.

- Use DEET in concentrations of 10 percent to 30 percent, but apply cautiously in children. Avoid concentrations above 30 percent.

- Apply permethrin to clothing and gear, not skin; it kills and repels ticks even after several washes.

- Use oil of lemon eucalyptus, which requires frequent reapplication due to quick dissipation.

- Consider picaridin, a nearly odorless and effective skin-safe alternative.

- Ask a veterinarian about safe tick repellents for pets.

- Use the Environmental Protection Agency’s online tool to find the right repellent for your needs.

3. Post-Outdoor Tick Safety

Taking quick action after being outdoors can help prevent tick attachment and reduce infection risk.

- Inspect yourself, children, and pets thoroughly for ticks, especially in hidden spots such as under the arms, behind the ears, inside the belly button, behind the knees, along the scalp, around the groin, and at the waistline.

- Bathe or shower within two hours of coming indoors to reduce the chance of tick attachment.

- Tumble-dry clothes on high heat to kill ticks, since washing alone may not remove them.

- Persistent fatigue: Experiencing ongoing tiredness, even after treatment.

- Inflammation and arthritis: Developing joint pain and swelling, especially in the knees, elbows, shoulders, wrists, ankles, or hips.

- Nerve damage: Experiencing weakness, pain, numbness, or tingling in various parts of the body due to nerve injury.

- Post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome (PTLDS): Developing ongoing symptoms such as fatigue, pain, or cognitive issues despite completing antibiotic treatment. About 10 percent to 20 percent of patients are affected. Further antibiotic therapy has not been shown to provide benefits when no active infection is present.

- Lyme arthritis: Experiencing persistent joint inflammation that does not improve after one or more courses of antibiotics. About 10 percent of patients with Lyme arthritis are affected. When no active infection is found, this condition is called postinfectious Lyme arthritis.

- Lyme carditis: Developing a rare but serious complication that affects the heart’s electrical system. This occurs in about 1 percent of cases.

- Neuropsychiatric complications: Experiencing intrusive thoughts, disturbing memories, or mood changes. Research suggests that about 34 percent of people with Lyme-associated illness may be affected, with some reporting suicidal or even homicidal thoughts.