In 1989, Kent Nerburn decided to take a job as a cab driver. “What I didn’t count on when I took the job was that it was also a ministry. Because I drove the night shift, my cab became a rolling confessional,” Nerburn, now an award-winning author from Minnesota, wrote in a story from his book “Make Me an Instrument of Your Peace.”

“I encountered people whose lives amazed me, ennobled me, made me laugh, and made me weep. And none of those lives touched me more than that of a woman I picked up late on a warm August night.”

He arrived at the given address. “But no one came out. And I thought, ‘Well, I’d better decide, do I go up and knock on the door? Do I just wait here?' A lot of drivers would have just taken off,” Nerburn told The Epoch Times.

He decided to go knock. A woman came to the door. She appeared to be in her 80s.

The woman asked, “Would you help me carry my suitcase out to the car?”

“Sure,” he said. That’s when the woman told him: “I’m going to the hospice. The doctor said I have to go.”

She got in the cab, sat in the back, and asked: “Can we drive through the city? This will be the last time I‘ll see this. I’d like to pass by some of the places that were important in my life.”

“She took me by a dance hall in part of the city, and said this is where she and her husband first met. She took me by the houses where she lived. She took me by a hotel where she had been an elevator operator,” he said.

“We just drove through the city the whole night, and it was getting late and early in the morning, and she said, ‘OK, I’m tired. Let’s go now.’”

Nerburn drove her to the hospice. As she got out of the cab, she asked, “Well, how much do I owe you?”

“You don’t owe me anything,” Nerburn said.

“Oh, you have to make a living,” she said.

“There are other fares, don’t worry,” Nerburn replied.

Nerburn helped her get her bag out of the car, and the hospice staff were waiting for her with a wheelchair. She then went over, gave Nerburn a big hug, and said, “Thank you for doing this.”

“It was one of those moments that makes you think,” Nerburn said. “Maybe that is what I was put on earth to do at that particular moment—to help that woman.”

On the surface, being kind benefits the recipient, but by giving, you—the benefactor—also gain in meaningful and tangible ways. The effects of kindness manifest concretely in scientific data—and even in your DNA.

Kindness Changes Your Inner World

Kindness is part of human nature. Scientists have found that children as young as 18 months can demonstrate clear intentions to help others.

Acts of kindness usually begin with empathy. As we feel compassion for others’ suffering, we are inclined to free them from it, motivating acts of kindness.

In those moments, our brain’s “empathy circuit” lights up.

Building on decades of neuroscience research, we know that when mirror neurons activate, we feel or react in ways that reflect those whom we are observing. Our brains, to a certain extent, experience a degree of overlap between the experience of others and our own.

Moreover, kindness goes beyond the desire to free people from suffering and includes an intention to improve others’ well-being without expecting anything in return.

Yet when you give, something is inadvertently gained that engenders beauty in your own inner world.

In a 2023 study out of Australia, 671 participants set off on a two-week experiment in living well. The participants were randomly assigned into four groups: One group was asked to be kind to themselves; the second, to be more outgoing and sociable; the third, to engage in activities such as art or music appreciation; and the fourth, to engage in acts of kindness for others. Then, day by day, the researchers checked in about how these activities made the participants feel.

When it came to “eudaimonia”—a deep sense of purpose and fulfillment—helping others trumped all of the other activities. While self-care, socializing, and exploring art evoked positive feelings, they couldn’t compete with the warm afterglow that others experienced through engaging in acts of kindness.

(Illustration by The Epoch Times)

Naturally, kindness cultivates happiness. In a 2019 study published in The Journal of Social Psychology, researchers found that people who performed kind acts every day for seven days experienced a significant increase in happiness. Interestingly, whether people were kind to their family or to strangers, the more kind deeds they did or observed, the happier they were.

Furthermore, kindness affects more than emotions—it influences one’s DNA—shaping how the immune system works.

Good Deeds Change Your DNA

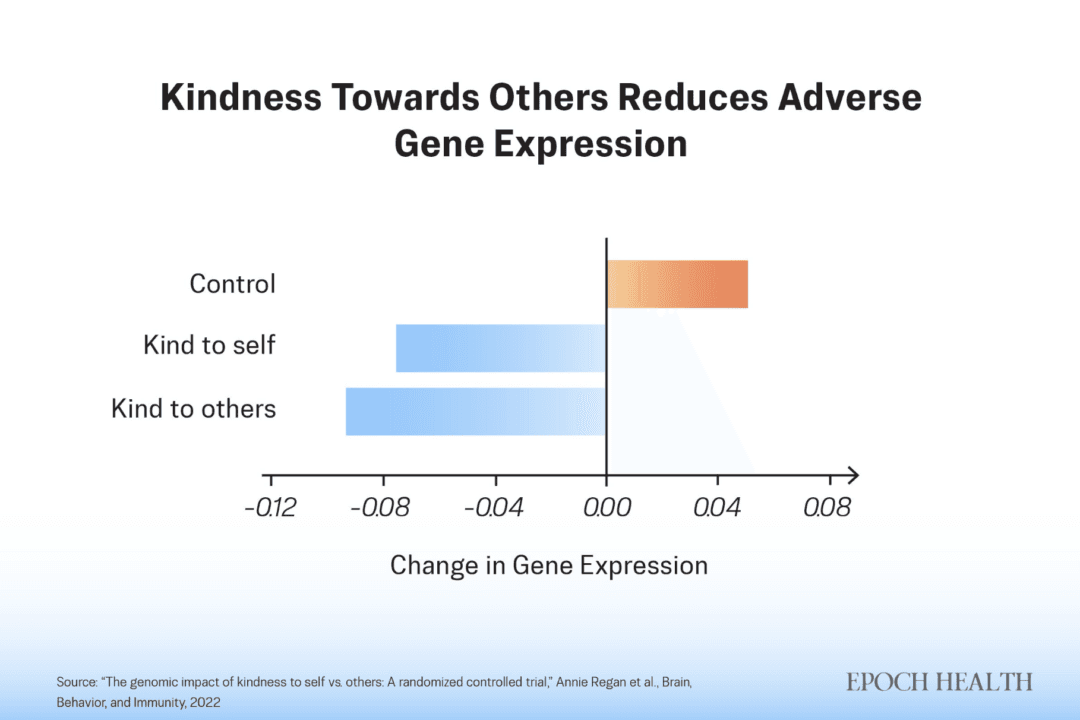

A group of scientists from the University of California set out to discover whether being kind to others changes our bodies at the genetic level.

To empirically test their query, researchers randomly assigned adults to three groups for four weeks: One group performed kind acts for specific people, another performed kind acts for themselves, and the last group performed a neutral activity as a control.

At the beginning and end of the study, the participants gave blood samples. The scientists looked for changes in a set of genes linked to inflammation and stress. Genes that, when overactive, are associated with a higher risk for diseases such as heart problems.

The findings were fascinating. The group that performed kind acts for other people showed the greatest healthy change in their gene activity in immune cells. The blood samples showed reduced expression of genes tied to inflammation and stress.

(Illustration by The Epoch Times)

Their finding corroborated one of their earlier 2017 studies, in which they concluded, “No costly, instructor-led, or labor-intensive activities were required; simply incorporating small acts of kindness toward others into daily routines was sufficient to alter leukocyte gene regulation.”

Ripple Effect of Kindness

“Most human behaviors, emotions, and traits are at least somewhat socially contagious,” Abigail Marsh, neuroscientist and empathy researcher at Georgetown University, told The Epoch Times.

Seeing other people doing kind deeds triggers the witness’s brain circuits to mirror kindness, priming them to be kinder themselves without conscious effort.

A famous parable tells of how a storm left thousands of dying starfish stranded on the beach. A man watched as crowds gathered but did nothing. Then a child began picking up the starfish one by one, throwing them back into the sea. “Son,” the man said, “don’t you realize there are miles and miles of beach and hundreds of starfish? You can’t make a difference!” The child smiled, picked up another starfish, threw it into the ocean, and replied, “I made a difference to that one!” The man was moved. He joined in, then one by one, the whole crowd joined.

As data suggest, single acts of kindness may spread farther than you think.

Research by Adam Grant, a professor at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, corroborates the contagious element of kindness in what he calls “upstream reciprocity.” In controlled experiments, participants who witnessed someone helping another person were 26 percent more likely to help a random stranger later.

Social scientists James Fowler and Nicholas Christakis conducted a landmark study showing that generous behavior spreads through social networks up to three degrees of separation. Their study, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a top-ranked journal, found that when one person acts generously, it inspires others to act generously toward a wide range of different people, creating a chain of kind acts.

When one person acts selflessly, they found, it inspires their friends and even their friends’ friends to be more generous as well. The ripple continues up to a third layer, moving like a wave through human networks.

One person's generous behavior spreads to three people removed from them—a friend of a friend of a friend—and each affected person continues to act generously in future interactions. (Illustration by The Epoch Times)

How far can kindness realistically travel?

In the 1960s, American psychologist Stanley Milgram conducted an experiment that found people could reach any stranger through an average of 5.2 intermediaries. This is the so-called small world problem, that is, we are far more connected than we realize. With technology, the world has become even smaller—reduced to 3.57 intermediaries, according to research conducted by Meta.

Even now, Nerburn’s story of helping the older woman 40 years ago continues to make a ripple. Nerburn shared that after his story appeared on the internet, he received countless emails, especially from young people, who were deeply inspired by the story. The tale has motivated many of them to act more kindly in their own lives, believing that a simple act of kindness can make a meaningful difference.

Developing Kindness

In a study published in Psychological Science, researchers recruited volunteers and randomly assigned them to either an eight-week mindfulness training or a control activity.

At the end of the experiment, participants believed they were reporting for an unrelated task in a waiting room. There, an actor on crutches passed by. “The sufferer [actor], who visibly winced while walking, stopped just as she arrived at the chairs. She then looked at her cell phone, audibly sighed in discomfort, and leaned back against a wall,” the authors wrote.

What happened next was quite telling. Fifty percent of the meditation-trained group quickly gave up their chair, while only 15 percent of the control group did the same.

The authors noted that “meditation resulted in such a large effect—increasing the odds of acting to relieve another person’s pain by more than 5 times.”

Follow-up experiments confirmed that even shorter meditation interventions of three weeks nurture significant empathy.

Another way to develop kindness is by feeling that you are part of something larger than yourself. One approach is to go out and experience awe. In a 2015 study published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, a portion of the participants stood facing tall eucalyptus trees and gazed up at them for one minute, while other participants looked away from the trees, staring straight at a modern science building. The tree-gazing participants were more likely to later help someone and reported lower levels of self-importance.

Nerburn said that in his life, ever since the unforgettable car ride, he has found a few ways to incorporate intentional kindness.

“A simple model is [to ask], ‘Will doing the good thing mean more to the other person than it will inconvenience me?’” Nerburn said, “And when that’s the case ... do the right thing.”

Acts of intentional kindness can start small. Marsh suggests a formula: When X happens, then I will Y—with as much detail as possible. “Whenever I go through a door, I will pay attention to whether anyone is approaching and hold it open for them. ... When I see trash on the ground, I will pick it up,” she said.

“At first, it’s effortful and then it becomes habit.”

Nerburn concluded that moments of kindness—such as his cab ride—are unexpected, yet they come to people every day. When you notice them, “take the moment and be kind.”

“In the long run, your life is going to be a whole lot better,” he said.