By now the statistics are familiar: Fentanyl is killing Americans at an unprecedented rate—around 73,000 annually.

For those aged 18 to 45, it is the leading cause of death.

And it’s everywhere—tainting counterfeit pills; poisoning children and adults, addicts and first-time users; and overwhelming any potential response. As a deluge of pills and powder flows across the southern border, authorities regularly seize enough fentanyl to kill everyone on the planet, several times over.

Into this carnage, a windfall.

Nationwide, more than $50 billion is expected to flow from legal settlements with opioid manufacturers and distributors over the next two decades—with California in line to receive about $4 billion, divvied up among the state and local governments.

This money will now largely go toward abating illicit fentanyl—the third wave in an opioid crisis that began with prescription pain medication in the 1990s.

In the first two years, California state programs have primarily used their share for “harm reduction” efforts—including opioid overdose reversal medication, needle exchange, and public education campaigns aimed at destigmatizing drug use.

Nationally, experts and progressive advocates are keeping a close eye on settlement spending, in an effort to avoid the mistakes of Big Tobacco settlements and ensure funds go to actual abatement, rather than to municipal budgets.

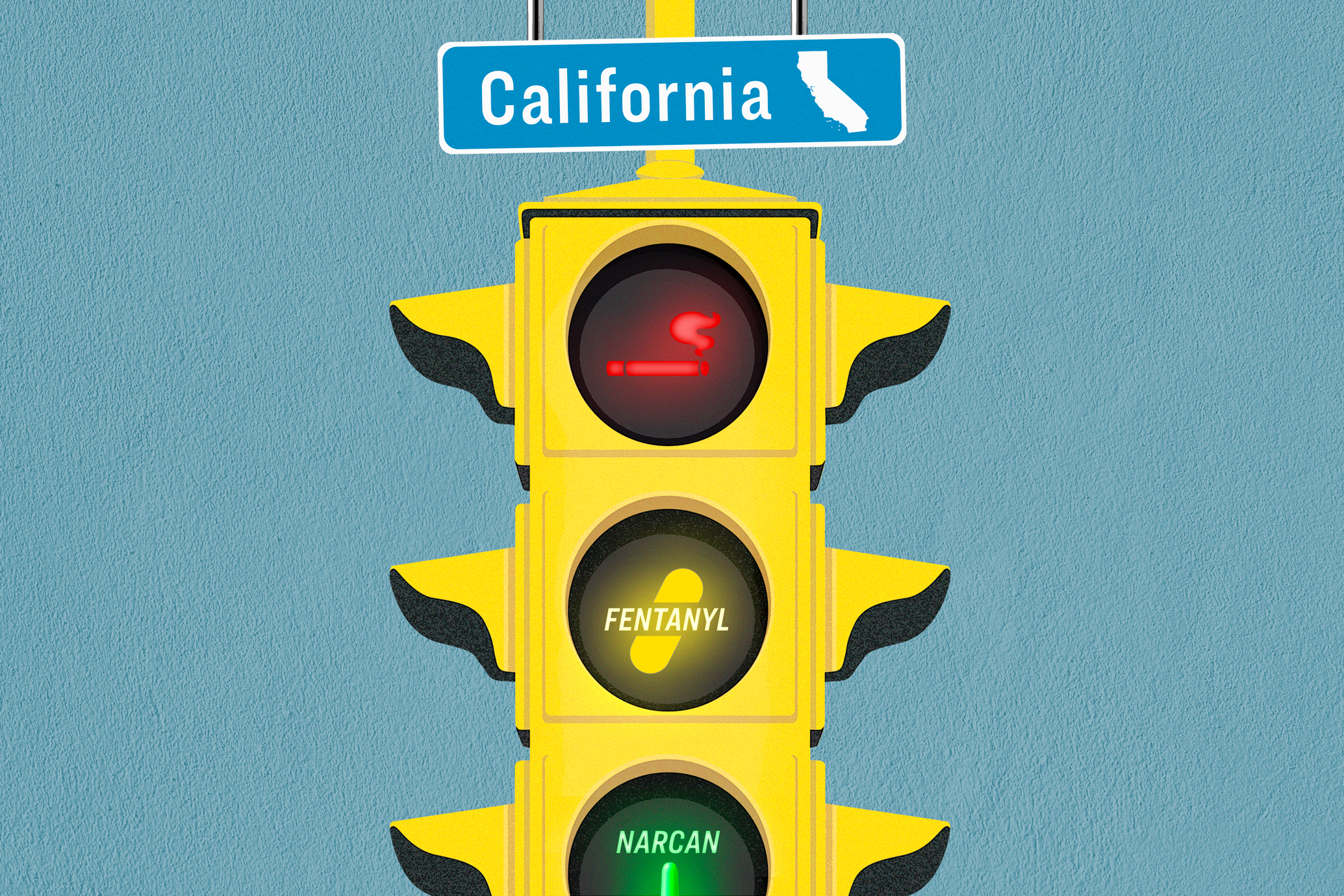

But some wonder if another obvious lesson from the fight against Big Tobacco—in which stigmatization, graphic warnings about the dangers of cigarettes, and enforcement led to a radical decrease in smoking—is missing from the state’s approach to the fentanyl crisis.

California’s Department of Public Health recently gave a San Francisco-based advertising agency $40 million in opioid settlement funds to produce a youth awareness campaign that aims to “meet people where they are” by reducing stigma around using fentanyl and other drugs and encouraging the use of naloxone.

According to state records, the department has also paid that same advertising company nearly $900 million to produce campaigns that expressly stigmatize tobacco use and encourage abstinence from it.

“In general, there is a strange contradiction between [California] Public Health trying hard to stigmatize tobacco smoking while destigmatizing fentanyl use,” Keith Humphreys, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University, told The Epoch Times.

By now, Humphreys said, the lessons from Big Tobacco are clear.

“Disapproving of smoking has been a life-saving thing,” he said. “And we should not be afraid to say to people that using fentanyl is incredibly dangerous and you shouldn’t do it.”

An anti-smoking poster issued by the California Department of Health Services adorns the back of a Los Angeles Metropolitan bus. (Hector Mata/AFP via Getty Images)

Harm Reduction Movement

Harm reduction is a social justice movement that seeks to reduce drug harms without judging, punishing, or even interfering in drug use. It is an explicit pendulum swing away from the War on Drugs of past decades, which state leaders continue to criticize as a “failed” approach.Many who are critical of the harm reduction movement in California, where it is orthodoxy—baked into the law—support harm reduction measures like naloxone distribution, medication-assisted treatment, and needle exchange.

What people tend to disagree on is whether hard drugs should be decriminalized and destigmatized; whether those using and selling them should be penalized when they break the law; and whether treatment can be coerced or, as many harm reduction advocates insist, can only happen when and if the person who uses drugs decides she is ready.

Humphreys supports harm reduction measures as part of a comprehensive, multi-pronged approach to the addiction crisis, and champions naloxone. As chair of the Stanford-Lancet Commission, he helped develop a national model for opioid response that recommends overdose rescue medications as “broadly the most lifesaving action policymakers can take.”

But he recognizes the limitations and has criticized the trend, prominent in blue cities, toward destigmatization of hard drugs.

“No one stops using drugs because of Narcan,” Humphreys said, citing recent research showing that those successfully treated with naloxone (the overdose reversal medicine sold under the brand Narcan) have a 13-fold increase in mortality compared to the general population.

“Twelve percent of people are likely to be dead from their addiction within 12 months of getting the Narcan,” he said.

Keith Humphreys, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University, poses for a photo in Stanford, Calif., on Aug. 29, 2016. (Marcio Jose Sanchez/AP Photo)

Further complicating the equation is the fact that non-opioids such as the “zombie drug” xylazine—which does not respond to naloxone—is showing up in nearly 30 percent of all fentanyl powder seizures. Moreover, there is no long-term research indicating how effective naloxone is after repeated use, or how the increasingly higher doses needed to reverse synthetic opioid overdoses affect people.

Meanwhile, naloxone has a shorter half-life than many powerful synthetic opioids—including nitazenes, an “emerging threat” in the U.S. drug supply—meaning people can overdose again after revival.

California’s current fentanyl awareness campaigns elide the ugly realities of using fentanyl—or meth, which killed nearly as many people in Los Angeles County last year—in favor of a message that works “in alliance with people who use drugs for safer and managed drug use.”

There are no photos of children who died from a single dose, no acknowledgement of the people suffering what amounts to a living death on the streets, no testimony from people who have recovered from their addiction.

“I don’t see one ad in here that says anything about treatment,” noted Gina McDonald, co-founder of Mothers against Drug Addiction and Deaths (MADAAD), a San Francisco-based nonprofit critical of California’s permissive approach to fentanyl.

“I eradicated my risk of overdose by stopping doing drugs—it’s the only foolproof way to prevent overdose,” McDonald, a former addict, said. “You would think that would be in at least one ad.”

According to 2024 statistics published by Mental Health America, a national nonprofit, nearly 83 percent of Californians with a substance use disorder, around 5 million people, did not receive needed treatment.

Narcan nasal spray sits in a vending machine by the DuPage County Health Department at the Kurzawa Community Center in Wheaton, Ill., on Sept. 1, 2022. (Scott Olson/Getty Images)

Nationally, only Illinois has a higher rate of untreated substance use disorder than California.

McDonald co-founded MADAAD with other mothers who have lost children to the streets—mothers with children currently addicted to fentanyl in places like San Francisco’s Tenderloin and Los Angeles’s Skid Row.

Their children are the intended targets of the state’s advertising campaigns—and the presumed beneficiaries of funds from a prescription opioid crisis that seeded subsequent heroin and fentanyl epidemics.

McDonald, like most everyone, wants to see Narcan everywhere—in every school and workplace and store—and knows what the shame of addiction feels like.

“I’m not saying we need to stigmatize drug users,” she said. “But how many times are people going to be Narcan-ed and go back to die another day? It’s usually what happens.

“I don’t know too many people who’ve been Narcan-ed on the street and went into treatment after being resurrected. ... Narcan isn’t dealing with any root cause of why people are using drugs.”

Representatives from influential policy organizations that advocate harm reduction and opiate decriminalization—including the National Harm Reduction Coalition and OpioidSettlementTracker.com—did not respond to inquiries.

Gina McDonald holds a poster of herself and her daughter at a protest in front of the Tenderloin Linkage Center in San Francisco on Feb. 5, 2022. (Cynthia Cai/The Epoch Times)

An Empathetic Conversation

Robert Marbut, the former executive director of the U.S. Interagency on Homelessness and producer of the forthcoming documentary “Fentanyl: Death Incorporated,” said the government is underreacting to an existential and continually evolving threat.“We absolutely have to get into drug education and prevention at a level that we did with cigarettes,” he told The Epoch Times, pointing to the nearly 75 percent reduction in smoking since 1965. Back then, nearly half of Americans smoked; now, around 12 percent do.

“[Those campaigns] said cigarette smoking is not cool—it’s dirty, it’s ugly, it’s awful,” Marbut said. “If you go look at the PSAs, they didn’t go into a sort of kinder, gentler thing. It was hard. It was direct. It was: ‘This is nasty. It’s horrible.’ And governments backed it up with real fines.”

Generally, harm reduction advocates say a softer, empathetic approach is needed to avoid the stigmatization and punitive tones of the War on Drugs. They argue that shaming or scaring people who use drugs will prevent them from seeking help.

Representatives of Duncan Channon, the ad agency behind California’s “Facts Fight Fentanyl” campaign, said they avoid the “fear and tragedy” of traditional PSAs in favor of an “approachable and empowering” way to talk about the fentanyl crisis and get people comfortable using naloxone.

“The last thing we are going to do is wag a finger at anybody or follow the failed tactics of ‘Just Say No,’ which has never really worked,” Duncan Channon’s CEO Andy Berkenfield told AdAge last year.

“The state strongly believes—and we are very much in line with them—that our job is to engage in empathetic conversation and ultimately reduce harm,” he told the industry publication.

Fentanyl destigmatization campaigns are common across the United States, and California’s opioid-settlement-funded “Unshame CA” campaign reports “measurable changes” in moving the needle on public perception of substance use disorder as a medical condition and naloxone as an everyday resource.

Executive Producer Robert G. Marbut Jr. attends the “Americans With No Address” Red Carpet Premiere at Harmony Gold in Los Angeles on Oct. 3, 2024. (Araya Doheny/Getty Images for Robert Craig Films)

Mixed Messages

But when does destigmatization become de facto normalization of extremely addictive drug use?Humphreys said he recalls a series of “Know Overdose” signs and billboards by the National Harm Reduction Coalition that appeared across San Francisco a few years ago, some of which showed fentanyl users as “attractive, successful, fun people—they were trying to say, ‘don’t feel bad about using fentanyl, it’s terrific, just do it with your pals and it will be safer.’”

While the state’s new fentanyl awareness campaign omits the billboards’ encouragements to “change it up” and “try smoking and snorting” instead of injecting, or “do it with friends,” it shares a tone and aesthetic lineage with these advertisements.

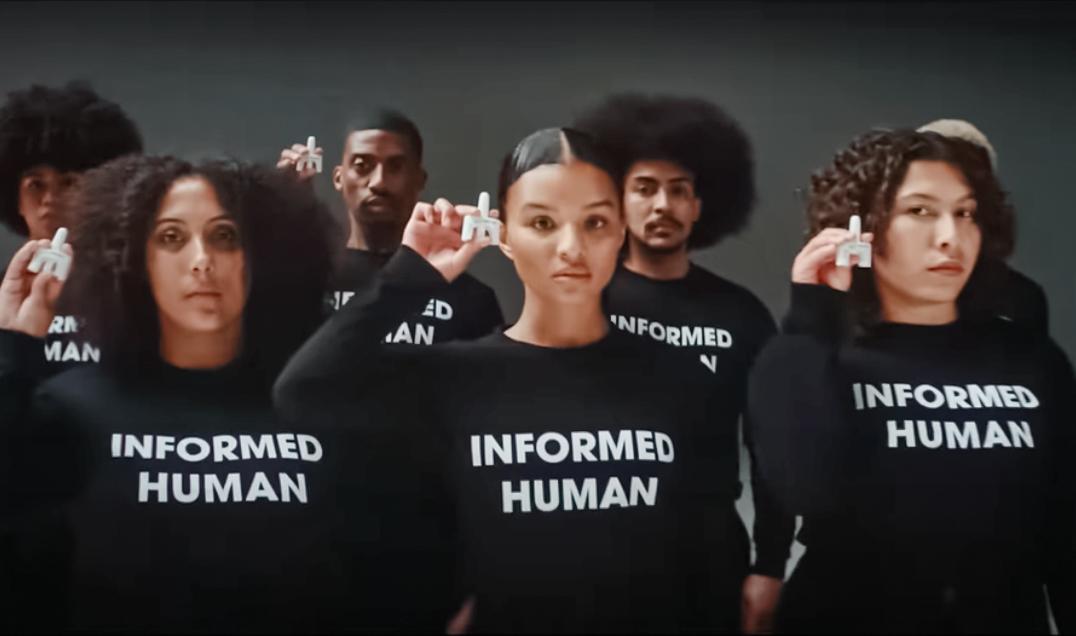

“Facts Fight Fentanyl” and “Informed Humans” use attractive actors in abstracted skits to deploy the message that fentanyl can show up in counterfeit pills and naloxone can save lives—all with an ethos of disaffected resignation.

In one spot, fentanyl is cast as the friend that wasn’t invited to the party. “Won’t be long until their friend, Overdose, shows up,” a voice says in the ad.

This is a stark contrast to the foreboding tenor and embrace of abstinence in California’s ongoing anti-tobacco campaign.

In the latter, a spot that takes inspiration from contemporary horror films, a voiceover narration tells you, “In Big Tobacco’s fantasy land, the deadliest industry is your friend.” Vaping won’t lead to smoking, it says, “if you ignore the research that says otherwise.”

Its other anti-tobacco ads are more direct, with slogans like, “Wake up,” and “Nicotine = Brain Poison.”

California acknowledges it has a problem getting minorities to fully accept its enthusiasm for a harm reduction approach to hard drugs, which the fentanyl awareness ads are meant to correct.

“Any creative and communications approach must meet people where they are at and reflect a nuanced understanding of their lives and cultural realities,” Robin Christensen, head of substance and addiction prevention at the California Department of Public Health, said in a statement last year on behalf of the fentanyl awareness campaign, which was designed for “Latine, Black/African and Asian Pacific Islander” audiences.

Screenshots of advertisement videos that raise awareness of overdose prevention medication. (California Department of Public Health/YouTube screenshot via The Epoch Times)

The “culturally relevant” messaging, she suggested, is meant to increase receptivity to harm reduction strategies among these populations.

Duncan Channon declined to comment about the fentanyl awareness and anti-tobacco campaigns designed for the Department of Public Health. Since 2014, California has paid the boutique advertising agency $876 million for anti-tobacco messaging, $76 million for COVID-19 vaccine public service announcements, and $40 million for opioid awareness campaigns, according to records reviewed by The Epoch Times.

Records of the state’s contracts are normally available for public view on its procurement portal.

In an email, the department said it had been billed $446.5 million during this time by the agency, its subcontractors, and associated vendors for media and production services related to anti-tobacco work. It said 83 percent was spent on media placement and 17 percent on “production, billable hours and other services,” and 95 percent of it was funded by tobacco taxes.

The department said California Tobacco Prevention Program media campaigns have contributed to a significant decline in the state’s tobacco prevalence, with youth tobacco use falling 46 percent and adult use declining 37 percent over the past decade.

A Double Standard?

The same harm reduction principles that dominate drug policy in California are vilified in relation to tobacco use.For instance, the state’s anti-tobacco campaign says it’s now battling Big Tobacco’s rebranding of itself with a focus on smokeless products. In a recent blog post, the Stanford School of Medicine highlighted the work of one of its professors, an expert in tobacco advertising.

“They’ve done something that is truly outrageous,” Dr. Robert Jackler, a professor emeritus of otolaryngology, told the blog about Big Tobacco’s infiltration of continuing medical education courses. One, titled “Harm Reduction from Tobacco,” taught that the health goal of all smokers should be “smoke-free, not tobacco/nicotine abstinent.”

“Only purveyors of tobacco products would assert that sustaining a nicotine addiction should be the primary goal in optimizing health—addiction is not wellness,” Jackler said.

A sign advertises cigarettes outside a shop in Los Angeles on April 28, 2022. (Mario Tama/Getty Images)

In the absence of an obvious villain like Big Tobacco, the same logic—that “addiction is not wellness”—does not seem to apply to hard drug use.

The dissonance is further illustrated in West Coast cities, where the government will give you a ticket for smoking a cigarette within a few yards of an office building while subsidizing fentanyl use through the distribution of paraphernalia, according to Marbut.

“Call it what it is—it’s promotion of fentanyl use when you provide all the supporting materials that are way more expensive than the active ingredient,” he said, referring to government-funded harm reduction programs that distribute syringes, foil, and pipes to addicts on the street.

“Why in the world would we use opioid settlement money that’s supposed to correct the mistakes of the past to fund the mistakes of the future?” he said. “We’re going to use [that] money to keep consumption going? You can’t put lipstick on this pig.”

The Department of Public Health did not respond to specific questions about its different approaches to tobacco and opioid messaging. In an emailed statement, the department said its public education campaigns are designed using “research-driven, multi-layered approaches” to address “unique and complex” issues like tobacco use and opioid overdose.

“While our goals with each effort may vary, we universally engage community-based organizations, health care providers and other partners to provide education, resources and prevention information that helps empower Californians to make informed decisions,” the department said.

“This in turn helps improve awareness, reduce stigma, and prevent harm, injuries, and deaths—and provides a gateway to more detailed information and resources provided by the state and its partners.”

Men are passed out after using drugs in Los Angeles on April 10, 2024. (John Fredricks/The Epoch Times)

‘The Last Mile’

Sam Chapman has spent years researching how to stop fentanyl from killing American children.His son, Sammy, was fatally poisoned after a dealer who found him on Snapchat delivered the drug to him at home, “like a pizza,” when his parents were sleeping.

Chapman’s advocacy work has largely focused on legislative reform, including Sammy’s Law, which, if passed, would require platforms such as Snapchat and TikTok to let parents use third-party software that would alert them when dangerous content is shared on their children’s social media accounts.

He has launched his own awareness campaigns, which include billboards with images of his son. Regarding the state’s approach, he said, “levity is hardly the answer.”

But even with great messaging, there are limits to education and awareness.

“This thing is so addictive—it’s not about education, it’s about stopping the delivery mechanisms,” he said. “It’s about taking social media out of the equation. The last mile.”

Social media platforms help dealers and traffickers reach young customers, and a new wave of bills is chipping away at the issue.

Chapman testified in favor of California’s Senate Bill 918, which will require platforms to comply with a search warrant within 72 hours. The American Civil Liberties Union opposed the bill, citing “unnecessary pressure on fundamental protections,” but it ultimately passed, and Gov. Gavin Newsom recently signed it into law.

But Chapman also said he thinks opioid settlement money—of which there is plenty, sitting collecting interest—should be used to staunch the flow of fentanyl.

“You want to warn parents about the dangers of social media and get them to limit its use,” he said. “Use the money to break the chain. Texas is doing the right thing if they use the opioid money to close up the border. California the same.

“We need to stop the chemicals coming in from China,” he said of the flow of precursor chemicals, subsidized by the Chinese Communist Party, that is fueling cartel-made illicit drugs.

Bill Bodner, former special agent in charge of the Los Angeles Field Division for the Drug Enforcement Administration, noted that street drugs are an evolving threat that change according to the whims and wiles of the cartels that produce them.

A U.S. Customs and Border Protection agent checks documentation at the San Ysidro Port of Entry in San Ysidro, Calif., on Oct. 2, 2019. (Sandy Huffaker/AFP via Getty Images)

“People get violently angry with me when I say this—but supply reduction is actually the most statistically supported form of harm reduction there is,” he said, pointing to CDC data showing harms from prescription opioids increasing or decreasing with availability.

“Supply reduction is harm reduction when you’re talking about all that mountain of synthetic drugs.”

Authorities can seize drugs, but prosecution is necessary to stop the cycle, he said, and California’s Prop. 47 has reduced or eliminated penalties for many drug-related crimes.

Bodner gave the example of a case in which a drug dealer sold drugs that caused seven overdoses and three deaths over a single weekend. What happens when the dealer is released? “More deaths,” he said. “We have to decide as a society, are we OK with that?”

Imagine if prescription drugs were tainted with poison, he said. “Why don’t we have that response on the law enforcement side?”

A Perfect Storm

In California and in the United States, data show the rate of increase in drug overdose deaths finally beginning to subside. Meanwhile, those who work with addicts on the streets in San Francisco say a combination of interdiction and a weakened fentanyl supply is having a remarkable effect.“We’ve been seeing a big drop in potency here, and the cost of a gram on the street right now is $80 as compared to $5 to $10 last year at this time,” McDonald said. According to her, the expensive, degraded high is pushing more people to seek treatment.

This could also be the result of increased pressures on China’s precursor market, the crackdown on cartel trafficking, or any number of other factors affecting the availability and quality of supply. McDonald said she is interested less in why it’s happening than in what can be done before it shifts again.

“All I know is, in California we are completely unprepared for the perfect opportunity that has come from all of that to move people into treatment,” she said. “There are no beds. “We get calls all the time saying, ‘Can you help my kid?’”

Like state programs, counties and cities in California have largely prioritized harm reduction projects with the first arrival of opioid settlement money. A few, including Los Angeles, have allocated funds for treatment infrastructure.

People use drugs in the Tenderloin District of San Francisco on May 16, 2024. (John Fredricks/The Epoch Times)

All municipalities were required to submit updated expenditure reports for this fiscal year at the end of September, which the Department of Health Care Services has said it will eventually make public.

According to the most recent polling, an overwhelming majority—71 percent—of likely voters in California say they will vote for Prop. 36 in November, which would roll back some of the more controversial changes introduced by Prop. 47—including the infamous $950 retail theft threshold.

Prop. 36 would increase penalties for fentanyl and give those caught with the drug a choice between treatment and prison.

“That would be a start,” Chapman said. “Why not direct opioid settlement funds to those beds?

“That’s restorative justice.”