News Analysis

The long-awaited U.S.–China meeting in South Korea on Oct. 30 ended with a truce that lowered tariffs and halted a spiraling trade war between the world’s two biggest economies.

China is now buying soybeans again after a months-long hiatus. The rare-earth minerals will flow out again. And the tit-for-tat port fees are on pause.

The two national leaders both hailed the meeting as highly positive. President Donald Trump rated it a 12 out of 10. Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leader Xi Jinping called it “a new start.”

Tune in to China Watch, a podcast on Chinese politics, technology, and business.

But behind the friendly banter, the question of how long the detente lasts—and whether the CCP will renege on its promises—is another matter.

“It’s a diplomatic painkiller,” Sun Kuo-hsiang, an international affairs professor at Taiwan’s Nanhua University, told The Epoch Times. “It alleviates the symptoms for the moment but leaves the root cause untouched.”

Chinese economy analyst Christopher Balding compared the situation to a “cease-fire.”

“Most cease-fires are very fragile,“ Balding, founder of New Kite Data Labs, an open-source intelligence entity that researches the Chinese economy, told The Epoch Times. ”They don’t last a long time.”

Everything Beijing has done so far, Sun said, smacks of a classic regime tactic: kicking the can down the road.

A Delay Game?

The landmark meeting on Oct. 30 was the first face-to-face encounter between Trump and Xi in more than six years.

After their talk, Trump said the two had “agreed on many things, with others, even of high importance, being very close to resolved.”

With the agreement came a rollback of threats and retaliatory measures from the preceding months. China’s reciprocal tariffs, imposed since March, will pause and its purchases of U.S. soybeans will resume. The sweeping rare-earth export controls imposed in October will stop for a year. Beijing also promised to crack down on the smuggling of fentanyl precursors in return for a 10 percent China tariff cut.

The U.S. Soybean Export Council booth at the eighth China International Import Expo in Shanghai on Nov. 5, 2025. China stated on Nov. 5 that it would extend for one year its suspension of additional tariffs on U.S. goods, formalizing an agreement reached the previous week between U.S. President Donald Trump and Chinese leader Xi Jinping. (Hector Retamal/AFP via Getty Images)

But absent from the deal are glaring issues that overshadow the bilateral relationship. Among them are the fate of Taiwan, human rights, China’s military aggression in the Indo-Pacific region, structural issues with China’s industrial policy, TikTok, and semiconductors.

“There’s a lot of issues that they just didn’t deal with,” Balding said.

Sooner or later, he said, these issues will come back and break the temporary calm.

Beijing has indicated that it will fight for core interests. Several days after coming to the deal, Chinese Ambassador Xie Feng brought up Taiwan and human rights as among Beijing’s “red lines” in a video address.

The U.S. side, he said, should “avoid crossing them and causing trouble.”

Even the existing pledges remain abstract and tentative, according to Sun. The trade deal is up for review yearly. So are China’s loosening of rare-earth restrictions and Washington’s suspension of duties on China-linked vessels. In a year, any geopolitical headwinds, from the Russia–China relationship to Taiwan Strait tensions, could cause priorities to shift, Sun said.

Adding to the uncertainties is a Supreme Court review that will test Trump’s authority to impose global tariffs. The president on Nov. 6 said he plans to develop a “game two plan” but acknowledged that the alternatives would be “slow by comparison.”

The lack of details in the agreement gives Beijing a loophole to exploit, according to Yeh Yao-yuan, chair of the International Studies Department at the University of St. Thomas.

“Talking one way and acting in another—this is typical of the Chinese Communist Party,” Yeh told The Epoch Times.

Because the U.S.–China pact is short on specific targets, he said, the regime can play the delay game and not deliver anything tangible.

News coverage of the meeting between U.S. President Donald Trump and Chinese leader Xi Jinping in South Korea is shown on a television outside a shopping mall in Beijing on Oct. 30, 2025. The two leaders agreed to pause China's reciprocal tariffs, resume Chinese purchases of U.S. soybeans, temporarily lift rare-earth export controls, and curb fentanyl precursor smuggling. (Adek Berry/AFP via Getty Images)

False Hopes

The gap between promises and reality is a constant concern in Washington’s dealings with China.

To gain entry to the World Trade Organization, China agreed to open up its markets, eliminate trade barriers, and protect intellectual property rights. Years later, the assurances have largely proved empty. Chinese firms, under lavish state subsidies, flood markets with impossibly low-priced products. On counterfeits, China dominates the world.

In his first term, Trump sought to address Beijing’s unfair trade practices and the massive U.S.–China trade deficit by launching a trade war.

Rounds of tariff fights culminated in the phase one trade deal in January 2020. U.S. officials had hoped that it could rebalance the trade relationship. It did not; Beijing ended up falling far short of buying the $200 billion in U.S. goods and services it had committed to, blaming the COVID-19 pandemic for disrupting the plan.

During the Biden administration, a four-hour meeting in 2023 also led China to agree to a fentanyl crackdown. Despite the talks and rounds of bilateral working group meetings, the same fentanyl problem continue to plague the United States.

“The Chinese Communist Party doesn’t have a very good history on keeping promises,” Lucia Dunn, professor emeritus of economics at Ohio State University, told The Epoch Times.

Yeh called it doublespeak.

“Anything that doesn’t go in its favor, the [CCP] just won’t do it,” he said. “It will keep pushing them off.”

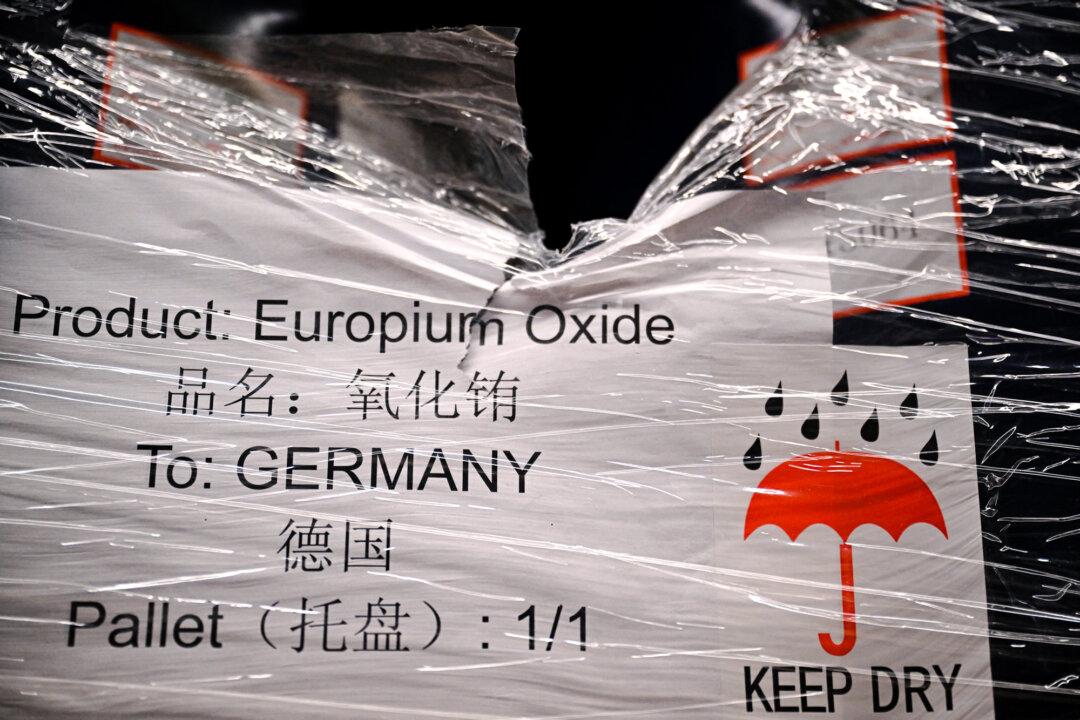

Decades of market manipulation, strategic state support, and aggressive investment have allowed China to capture rare earths and effectively hold the world to ransom. The recent export curbs are now spurring a reckoning.

“It wasn’t the [United States] versus China,” Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent said on CNN’s “State of the Union” on Nov. 2. “It’s China versus the world. They have shown themselves to be an unreliable partner in many areas.”

A container of europium oxide imported from China sits in the storage room of Tradium, a rare-earths trading firm, in Frankfurt, Germany, on Nov. 4, 2025. Decades of market manipulation, state backing, and aggressive investment have made China the world’s dominant supplier of rare-earth elements. (Kirill Kudryavtsev/AFP via Getty Images)

Forced Concessions

China has come to the negotiating table with a crisis brewing on the homefront.

Housing, once a pillar in the Chinese economy, has sunk into perpetual gloom, with even the top developers struggling to stay afloat. Sluggish overseas orders have shrunk China’s service growth to a three-month low. Youth struggle to find jobs. Millions of restaurants have shuttered.

In Kangle, a once-thriving garment hub in southeastern China, people crowd around hunting for odd work. With jobs drying up, migrant workers in several cities have packed up early to go home; one major textile factory sent its entire workforce on a four-month vacation, citing dwindling orders.

Weighed down by such economic pressure, China is seeking breathing room, according to analysts.

“Xi has to make concessions—only ... they are half-hearted concessions,” Yeh said.

Still, both sides appear eager to disentangle from each other.

Beijing, in laying out its plan for the next five years, envisioned a China with greater self-reliance, from technology to consumption. Warning of “high winds and rough waves,” the regime vowed to boost household consumption and accelerate manufacturing while forging a “national security shield.”

As Washington wrangles back rare-earth access from China, it is also racing to build a broad coalition to secure supply chain independence. Before meeting Xi, Trump allied with Australia, Japan, and four Southeast Asian nations on critical minerals. On Nov. 6, the president hosted leaders from five Central Asian countries rich in precious metals, stressing that he intends to make their partnerships “stronger than ever before.”

Bessent said, “We’re going to go at warp speed over the next one, two years, and we’re going to get out from under the sword that the Chinese have over us—and they have it over the whole world.”

On artificial intelligence, Trump has ruled out selling Nvidia’s cutting-edge chips to China, while Beijing has barred foreign semiconductors from state-funded data centers. An investigation into China’s compliance with the phase one trade deal, launched in late October, has continued despite the trade truce, potentially opening the door to new trade enforcement actions against China.

Technicians work on chip-processing equipment at a semiconductor plant in Suqian, Jiangsu Province, China, on Oct. 20, 2025. Trump has ruled out selling Nvidia’s most advanced chips to China, while Beijing has barred foreign semiconductors from state-funded data centers. (STR/AFP via Getty Images)

The ‘New Norm’

Bessent said the United States is looking to “de-risk” rather than decouple. But Balding said those are just buzzwords.

“I think you'd be hard-pressed to find clear definitions of those,” he said. “I’m not stuck on a word.”

In the long term, decoupling seems to be the inevitable trend, according to Wang Guo-chen, a research fellow at the Chung-Hua Institution for Economic Research.

“Both are preparing to decouple, it’s just that for now, neither is ready for the costs,” Wang told The Epoch Times.

The new dynamic marks a shift from the “mutual dependence and mutual benefit” that China has long promoted, according to political economist Davy J. Wong.

“Security and autonomy is the new norm,” he told The Epoch Times.

This makes any cooperation fleeting by nature, according to Yeh.

“When you are partners, everything is easy, but now the relationship has changed from partnership to competition, and not just any type of competition—it’s a life and death battle,” he told The Epoch Times.

On a deeper level, the split between Washington and Beijing is ideological, according to analysts.

The Chinese word for China translates to “the Middle Kingdom” in English. Balding said that although people in the West often understand the word “middle” to mean “between,” the Chinese term is closer to “center,” as in, “the planets revolve around the sun in the middle.”

“That’s how China thinks of itself,” he said. “It thinks it’s returning to the place it belongs, as the center of the world, as the center of the universe around which all other states and issues revolve.

“That puts it in very much fundamental disagreement with the United States to start off with, but a lot of other countries from there as well.”

Luo Ya, Yi Ru, and Fei Chen contributed to this report.