WASHINGTON—Over and over, Amy Neville forces herself to tell people what happened to her 14-year-old son.

“I relive it ... I’m out there sharing the hardest thing that’s ever happened in my life,” she said. “It’s worth it, because I know we’re saving lives.”

Neville, 52, wiped away tears as she spoke those words during an interview with The Epoch Times on June 23. That day marked five years since her son, Alexander Neville, unknowingly ingested fentanyl and died—a tragedy that could easily befall any family, she said.

Through the nonprofit Alexander Neville Foundation, the grieving mother shares her personal pain with other parents. By her estimation, Amy Neville has given a couple hundred presentations in person and online; about 300,000 people have heard her warnings about the dangers that lurk on social media, leading to deaths such as Alex’s.

Neville also serves as the lead plaintiff in a groundbreaking court case that could affect the way Big Tech operates in the United States.

She believes that changes are needed to prevent many deaths among young people who, like Alex, flock to Snapchat and other online platforms.

Neville and her husband are among 63 fentanyl victims’ families suing Snapchat. They allege that the platform is a defective product and a public nuisance and that it should be held responsible for fentanyl overdose deaths, poisonings, and injuries.

Snap Inc., parent company of Snapchat, “vehemently denies” the allegations, a judge noted.

In the suit, the Social Media Victims Law Center represents dozens of families whose children “died of fentanyl poisoning from contaminated drugs purchased on Snapchat,” Matthew Bergman, the Seattle-based center’s founding attorney, told The Epoch Times.

Snap did not respond to a request for comment.

Life Changed ‘Like a Light Switch’

Five years ago, the Nevilles were living in Aliso Viejo, California, a tree-lined suburb of Irvine that ranks among the state’s safest communities.

Neville was running her own yoga studio; her husband, Aaron, was working as a website developer. They were both in their 40s, parenting their daughter Eden—a “brainiac” who loved school—and their son Alex, a “super smart” boy who hated homework but loved history, skateboarding, and gaming, according to Neville.

They were an “ordinary” middle-class family, she said.

The mother of two said she remembered thinking that the biggest threat to her asthmatic son was probably the COVID-19 respiratory virus that was then spreading.

Alexander Neville, 14, reclines with family pets in an undated photo. Alexander died of fentanyl poisoning in June 2020 at the age of 14. (Courtesy of Amy Neville)

But that was life during the period Neville calls “the Before”—the era before the day that changed everything instantly, “like a light switch” being flipped, she said.

On the morning of June 23, 2020, Neville went to awaken Alex for a dentist appointment. Her knock on his bedroom door yielded no response.

So she entered the room. She confronted a horrifying sight: Her son, reclining in his favorite red beanbag chair—seemingly asleep, except his skin had turned cyanotic blue.

Clearly, he was dead. But as a mother, Neville could not let go of hope. Maybe her firstborn could be revived, she thought.

Neville blocked Eden, then 12, from seeing her older brother in that condition. Then she called for her husband, who performed CPR while she spoke to a 911 operator via cellphone.

When medics arrived, they took over CPR, strapped Alex to a gurney, and took him to a hospital, where he was pronounced dead.

The Nevilles were gobsmacked. But a clue soon surfaced.

“There’s a pill left behind in the room,” an investigator told Neville. She had not noticed it.

The unidentified pill was turned over to the federal Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).

“That’s when we learned about the fentanyl,” she said. “The pill tested positive for fentanyl.”

About Fentanyl—and Snapchat

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid that can be prescribed for managing severe pain or for anesthesia. But it can also be risky because it is far more powerful than morphine, is highly addictive, can interfere with breathing, and can cause confusion, nausea, and drowsiness. Abusers may be drawn to it because it can create a sense of euphoria.

(Left) Police seize a new variety of fentanyl during a recent drug bust that had been molded into the shape of a gummy bear in Lethbridge, Canada. (Middle and Right) Customs and Border Protection seizes approximately 47,000 rainbow-colored fentanyl pills, 186,000 blue fentanyl pills, and 6.5 pounds of methamphetamine hidden in the floor compartment of a vehicle at the port of entry on the U.S.–Mexico border in Nogales, Ariz., on Sept. 3, 2022. (Lethbridge Police Service, U.S. Customs and Border Protection)

While doctors can currently continue prescribing fentanyl, a Schedule II Controlled Substance, under tight controls, Congress recently passed a bill that permanently classified “fentanyl-related substances” as Schedule I drugs with “no currently accepted medical value.” Offenses involving those substances carry strong criminal, civil, and administrative penalties.

After President Donald Trump signed the bill on July 16, the Halt All Lethal Trafficking of Fentanyl Act became law.

Because fentanyl is cheap to produce, illicit drug dealers add it to other substances. They also substitute fentanyl for buyers’ requested drugs, despite how deadly it can be.

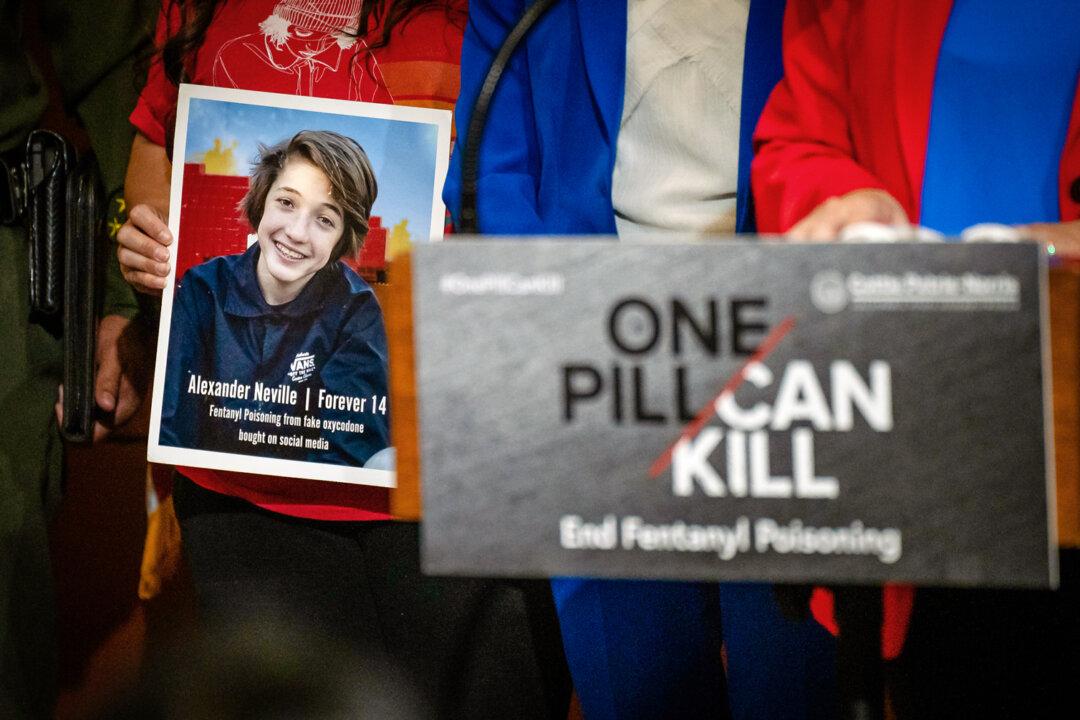

Even a pencil-tip-sized amount can prove fatal, as emphasized in the national “One Pill Can Kill” public awareness campaign. The DEA launched that program four years ago to combat dramatic increases in deaths related to counterfeit prescription painkillers; agents have been seizing millions of these fake pills each year. So far, that number exceeds 45.7 million, according to the agency’s website.

Fentanyl has been blamed for more deaths among teens and young adults than “COVID, car accidents, or even suicide,” according to the Snapchat lawsuit that Bergman filed along with C.A. Goldberg, a law firm in the New York City borough of Brooklyn that focuses on cases against tech companies.

The Neville suit argues that Snap contributed to an “epidemic” of fentanyl deaths.

“Social media platforms and Snapchat in particular ... allow drug dealers to ply their deadly trade at scale with relative anonymity, with relative legal immunity,” Bergman said.

He said stemming the fentanyl crisis at the national level requires not only cutting off the drug pipeline from foreign countries, but also “holding social media companies accountable, because they’re the primary vehicle” for the distribution of fentanyl-contaminated pills.

In 2023, more than 107,000 Americans died from drug overdoses, according to data from the DEA. Nearly 70 percent of those deaths were attributed to opioids such as fentanyl.

Fentanyl deaths of children aged 18 and younger surged more than 30-fold between 2013 and 2021, according to data published in JAMA Pediatrics in 2023.

More than 100 million Americans use Snapchat, including more than 20 million teenagers, Snap co-founder and CEO Evan Spiegel told Congress in 2024.

Looking Back

Alex’s death “blindsided us,” Neville said, even though his tragic end, in hindsight, fit with a revelation the teen had made on Father’s Day, two days before he died.

Neville said she remembers her son confessing during a kitchen-table discussion: “I have got to tell you guys something. I wanted to experiment with Oxy. I got it from a dealer on Snapchat. It has a hold on me, and I don’t know why.”

Alex was referring to OxyContin—an addictive opioid. He admitted to using the street version of that drug on-and-off for a little more than a week.

Pain pills sit on a table outside Los Angeles on June 4, 2025. Alexander Neville died of a fentanyl overdose after taking what he believed was OxyContin, purchased from a dealer on Snapchat. (John Fredricks/The Epoch Times)

Right away, Alex’s parents thanked him for disclosing his problem. They contacted a treatment center where they intended to enroll him.

The next day, Neville took her son to get a haircut.

It would be his last.

Neville remembers admonishing her son that day.

“Please don’t take any pills tonight,” she said.

He promised that he would not.

By the next morning, he was dead—after apparently taking what he thought was OxyContin.

Neville said that back then, it never occurred to her that the pills could be laced with—or replaced with—a deadly drug.

“We didn’t know about fentanyl,” she said. “Nobody was talking about it at the time, and no one was talking about the depth of social media harms.”

Neville had “spot-checked” her son’s social media accounts for any hint of sexual predators or bullies. But she was unaware of the emojis that teens and drug dealers use to trade coded messages about drugs.

Now Neville includes that information in her messages to parents as she traverses the nation.

Amy Neville, whose 14-year-old son Alexander died from fentanyl poisoning after buying a pill on Snapchat, speaks during Social Media Victims Remembrance Day at Upper Senate Park on Capitol Hill in Washington on June 23, 2025. (Madalina Kilroy/The Epoch Times)

Snapchat Features Debated

On Snapchat, users exchange “Snaps”—texts, videos, and photos—that can vanish after a specified time.

That disappearing-message feature is intended to maintain privacy and allow people to “express whatever’s on [their] mind at the time—without automatically keeping a permanent record of everything [they have] ever said,” Snapchat’s website states.

That is a big reason Snapchat appeals to users, according to the company. That feature also distinguishes Snapchat from other platforms. Snapchat’s logo—a stylized ghost—represents the ephemeral nature of its messaging system.

This disappearing act allows drug dealers and other predators to evade law enforcement—while widely promoting illicit drugs, critics say.

“It’s like you put your drug ad up on a billboard at Times Square ... but the evidence disappears,” Bergman said.

The company’s website reads, “We work with law enforcement and governmental agencies to promote safety on our platform.”

The company also advises users that “some information may be retrieved by law enforcement through proper legal process.”

Snapchat has other features that are cause for concern, critics say.

Bergman alleged that Snapchat routinely connects “predatory drug dealers with vulnerable teenagers who are not seeking to purchase drugs.”

In its court filing, the company countered that it works hard to detect and intercept drug traffickers and responds rapidly to reported illegal activity.

In 2024, the company changed its Snap Map feature to improve safety. Now users’ locations are hidden by default—and parents can “see which friends their teen shares their location with,” the company stated.

Another point of contention is the allegedly addictive nature of social media platforms.

Some of the most brilliant U.S. minds formulate computer algorithms that analyze users’ actions and reactions. Then the system “feeds” people more content of the type that is likely to keep them mesmerized. The platforms also set up features designed to prolong usage. The longer a user stays on a platform, the more money-making advertising he or she is likely to see—boosting the company’s profits.

Snapchat, for example, rewards users with “Streaks,” scores based on repeat usage.

When parents take away teens’ phones, some have admitted to “literally crying on the floor ... because their ‘Streaks’ will be interrupted,” Bergman said.

Steve Filson (L), whose daughter Jessica died of fentanyl poisoning in 2020, and Amy Neville (R) join a march to protest outside Snap Inc. headquarters in Santa Monica, Calif., on June 4, 2021. The group called for stronger parental controls on the Snapchat app, better tools to block illegal drug sales, and greater cooperation with law enforcement. (Patrick T. Fallon/AFP via Getty Images)

Moving Forward

Now living near Tucson, Arizona, Neville fields phone calls from distressed parents and teens alike, providing information and connecting them with others who can help—not only with online drug trafficking issues, but also with other social media harms.

Her role as an advocate has given her an inside look at social media.

“When I started talking to kiddos about the drug stuff, and I asked what they’re seeing on social media, it led to conversations about other harms,“ Neville said. ”And so that’s when I was like, ‘This is bigger than just fentanyl drugs being sold.’ There’s the bullying; there’s this extortion; there’s this exploitation. ... And I’m like, ‘It doesn’t have to be that way. We don’t have to accept this.’”

Neville said she knows that her work is saving lives, although she has no way to count how many.

“When I go into schools, I give kids my personal contact information,“ she said. ”Like I always tell them, ‘You can reach out to me with anything—no questions asked, unless you’re in danger, then that changes the dynamic of what we’re talking about.'”

After one recent call from a girl who was talking about killing herself, the girl’s school principal blew off her threats of suicide as the words of “a drama queen,” Neville said.

But Neville said she believed that the young lady was at imminent risk of suicide.

“She had the means,“ she said. ”She had the [suicide] letter. She was ready to go ... but she felt comfortable telling me.”

She connected the teen with professionals.

Amy Neville speaks at a town hall meeting on fentanyl in Laguna Niguel, Calif., on April 12, 2023. (John Fredricks/The Epoch Times)

Big Tech Cases Exert Big Impact

Bergman calls it “the most important work” he has ever done in more than 30 years as a lawyer.

That is largely because of the effects on victims’ families, he said, but it is also because the cases are making legal history.

Currently, the lawsuit against Snap involves 63 fentanyl victims’ families from multiple states, including the Nevilles.

Bergman said a half-dozen bellwether cases are likely to be selected to chart the case’s direction at a hearing set for Aug. 25.

More families could be added to the lawsuit later. More than 160 families whose children suffered fentanyl poisonings have asked the center for legal representation, Bergman said. The victims were aged 14 to 22. All but two died; those survivors suffered lasting effects.

Pending since 2022, Neville v. Snapchat has already cleared key legal hurdles.

It is proceeding in California—where the Nevilles lived at the time of Alex’s death in 2020 and where Snap is headquartered.

The case centers on an emerging area of law that has yet to be tested by the U.S. Supreme Court, Bergman said, so “every decision that is rendered by any court is noteworthy.”

In court, Snapchat’s lawyers argued that a section of federal law has long shielded social media companies from liability for content that users generate.

But that law—Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996—has faced increasing court challenges. Critics say it is outdated and should not apply to the way social media companies now operate, as algorithms are used to influence users’ interactions with the platforms.

In the Neville case, Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Lawrence Riff ruled that “the alleged attributes and features of Snapchat cross the line into ‘content.’”

A photo of 14-year-old Alexander Neville, who died after accidentally taking fentanyl, sits on display in Irvine, Calif., on April 28, 2023. (John Fredricks/The Epoch Times)

Other courts have made similar findings, the judge noted in his January 2024 decision to deny Snap’s motion to dismiss, overruling nearly all of the company’s challenges to the legal sufficiency of the lawsuit’s claims.

Late in 2024, a California court of appeals upheld Riff’s ruling, allowing the lawsuit to move forward.

As a result, the plaintiffs’ lawyers are gathering information from Snap’s internal documents and sworn testimony from the company’s employees.

“[The goal is] to learn what the company knew about the sale of fentanyl-contaminated drugs on Snapchat, when the company knew about it, and why Snap allows these deadly sales to continue,” Bergman wrote on the law center’s website.

Company Defends Its Practices

Spiegel was among several Big Tech leaders whom the Senate Judiciary Committee summoned to testify early in 2024.

Senators explored mounting concerns over unregulated, unaccountable social media companies exposing young people to sexual predators, drug traffickers, cyberbullies, and content that glorifies risky behaviors, suicide, or violence.

In written testimony to the Senate committee, he said, “We want Snapchat to be safe for everyone, and we offer extra protections for minors to help prevent unwanted contact and provide an age-appropriate experience.”

The platform has also alerted its users about “the risks of fentanyl poisoning and counterfeit prescription drugs,” Spiegel said.

Bergman contends that the measures taken thus far are insufficient.

“Snapchat has not materially changed to protect children,” he said.

Bergman feels an urgent obligation to force Snap to improve its age-verification, parental-control, and danger-reporting systems.

“It really is a life-and-death situation,” he said. “Teenagers make bad decisions. They don’t deserve to die for them.”

Evan Spiegel (L), CEO of Snap Inc., arrives for a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing in Washington on Jan. 31, 2024. Big tech leaders testified on child sexual exploitation, drug trafficking, cyberbullying, and harmful content on social media. (Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images)

Memories of Alex

Happy memories of Alex still bring smiles to his mother’s face.

She laughs when asked to think back to the day he was born, May 4, 2006; it seemed to portend a rocky road.

“I always joke that Alex was moody from the second he was conceived,” Neville said.

While pregnant with him, she constantly felt sick and suffered blackouts.

“I couldn’t drive anymore after he was born, and he was colicky for four months,“ she said. ”That was hard. Then he had night terrors. ... It was a roller coaster, but we got through it. We were there for him.”

Alex, a former Cub Scout who once dreamed of directing the Smithsonian Institution, was a caring, introspective young man who “courageously fought his impulsiveness,” his obituary reads.

Alex’s parents always sensed that with that type of personality, Alex—like many teens—might go through “an experimental phase,” his mother said.

That is what happened.

Frustrated with an inability to measure up to his own expectations to excel at everything he did, “Alex began to hurt inside, and he got tired of trying so hard,” the obituary reads.

He turned to marijuana to “self-medicate,” then to counterfeit OxyContin, unaware that he would instead encounter a fatal fentanyl dose.

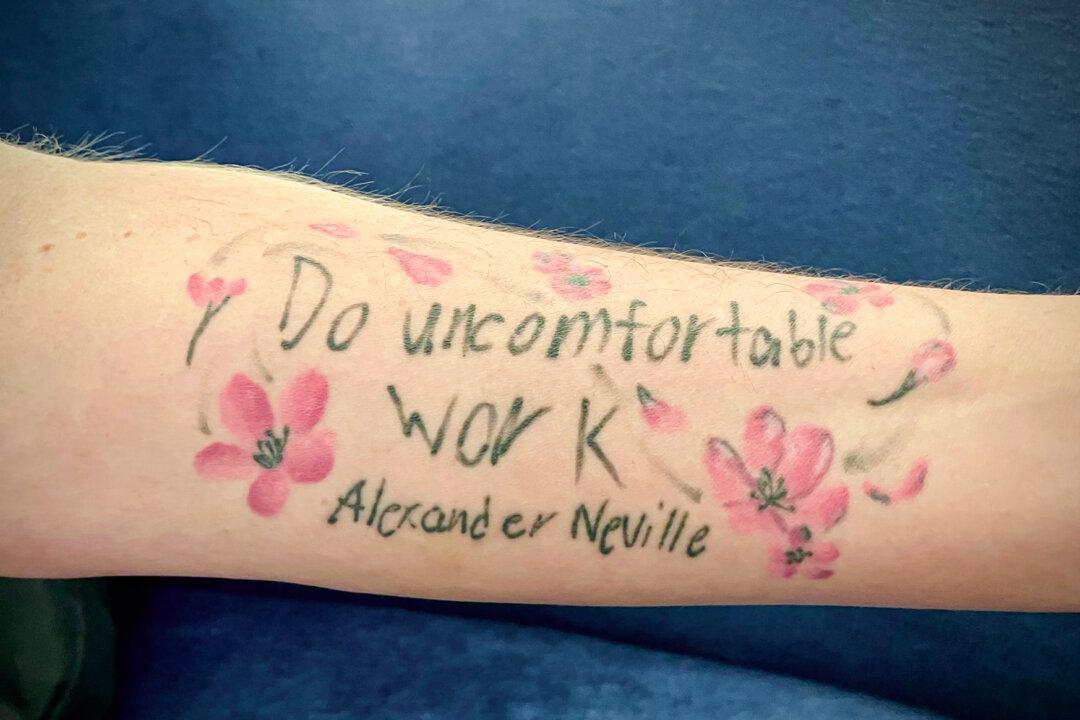

After her son’s passing, Neville struggled to recall the wording of an inspirational statement her son had scrawled on a piece of paper affixed to his bedroom wall.

One day, an image of that paper surfaced among photos on her husband’s cellphone. It reads, in part, “do uncomfortable work.”

Those words, replicated in her son’s handwriting, are now permanently tattooed inside Neville’s left forearm.

Amy Neville displays a tattoo on her left forearm reading “do uncomfortable work” in her late son Alexander’s handwriting, on the five-year anniversary of his death from fentanyl, in Washington on June 23, 2025. (Janice Hisle/The Epoch Times)

That saying has become her “mantra,” Neville said, inspiring her quest to help others—in honor of her son.

“Every day you have to live without your kid is hard, right?” she said. “But it would be harder to not do anything about it.”