Western wind, when will thou blow

The small rain down can rain?

Christ, if my love were in my arms

And I in my bed again!

This anonymous medieval poem, “

Western Wind,” is a brilliant bit of verse. It’s a prayer of petition, a lament, and a longing for home, all rolled into four short lines with only two words longer than a syllable. It also compounds three themes of medieval poetry: the weather, religious faith, and romantic love.

Perhaps most importantly, this little jewel has resonated down through the ages from “a world lit only by fire”—as historian William Manchester famously described the Middle Ages—to today, a world lit by screens.

Other poems from that pre-modern era invite our attention: first for their wisdom, beauty, and wit, then for their cultural landscapes and personalities, and finally for the mirror they create in which we, their judges, become the judged.

An illustration of scenes from a 1455 translation of "Memorable Deeds and Sayings" by Valerius Maxiumus. In the literary world, the medieval period was a time of vibrant color and preservation of ancient texts. Here, the sayings of Roman philosopher Valerius Maximus are depicted in a contemporary medieval environment. (Public Domain)

Adam’s Happy Fault

It was the Age of Faith, and therefore it was natural that writers penned songs, poems, and meditations on God, Christ, the Virgin Mary, and Scripture. Bede’s “Ecclesiastical History,” Chaucer’s “The Canterbury Tales,” and most works produced between the two reveal a culture imbued with Christian belief.

Written before 1400 by “Anonymous”—that most prolific of medieval writers—“Adam Lay Ibounden” is one such poem, providing a twist on the Genesis story of Adam and Eve.

Adam lay ibounden,

Bounden in a bond;

Four thousand winter

Thoght he not too long;

And all was for an appil,

An appil that he tok,

As clerkes finden

Wreten in here book.

Ne hadde the appil take ben,

The appil taken ben,

Ne hadde never our lady

A ben hevene quene.

Blessed be the time

That appil take was.

Therefore we moun singen

“Deo gracias.”

In this verse, which was also a carol, Adam spends 4,000 years in a special purgatory, all for the sake of an apple. The poet then adds the “felix culpa,” or happy fault, of Adam’s sin. Had he not taken a bite from that apple of knowledge, Mary would never have been heaven’s queen. “Therefore we may sing/ ‘Thanks be to God.’”

Here is wit at its best, turning on its head the usual interpretation of the Fall. The poem reminded listeners and readers then and now that sin, goodness that has been twisted, can be reshaped once again into a positive.

Death Without Blinders

In our day, death comes to many in hospitals and nursing homes. In the Middle Ages, however, death indiscriminately visited castle and cottage. Lord and liege, merchant and serf—all were well acquainted with the miseries of dying and the finality of the grave. Consequently, those who wrote of death were often far blunter in their language than we are today.

“When the Turf Is Thy Tower” serves as a memento mori, a written reminder of death as bareboned in its language as those skulls that some monks placed in their scriptorium. Here is the modern translation:

When the turf is thy tower,

And thy pit is thy bower,

Thy skin and thy white throat

Shall be food for worms.

What help to you then

(Is) all the worldly hope?

The poem reminds its readers that the goods of this world are useless as a counterweight of comfort to the certainty of death. The delivery of this message is brief and harsh; the reality, as the anonymous poet and his peers knew well, is assured.

"Death of King Louis IX at Tunis, 1270," 15th century. Medieval artists depicted mortality striking kings and peasants alike. (Public Domain)

Laughter and Love

The views of medieval men and women on love and sex ran the gamut from romance to ribaldry. By way of example, the Arthurian tales generally promoted the ideals of courtly love, while Chaucer explored the bawdy in “The Miller’s Tale.”

Politician, courtier, and lyric poet Sir Thomas Wyatt (1503–1542) had one foot in the Middle Ages and the other in the English Renaissance. With the wit that marked the times, in “Alas Madam Stealing a Kiss,” Wyatt urges a lady to retrieve the kiss he has taken from her and so protect herself in the future from his advances.

Alas, madam, for stealing of a kiss

Have I so much your mind there offended?

Have I then done so grievously amiss

That by no means it may be amended?Then revenge you, and the next way is this:

Another kiss shall have my life ended,

For to my mouth the first my heart did suck;

The next shall clean out of my breast it pluck.

By granting him the pleasure of another kiss, the poet assures the lady she will destroy his affections. It’s an amusing argument, which surely left some of its readers, as it may leave some of us, wondering whether to employ this means of seduction.

Our current age with its straitlaced sexuality bereft of affection has ruined such flirtation. Our so-called sexual liberation with its attendant and widespread pornography has diminished the rites of romance and courtship and shrouded the innocence and even humor that were their handmaids. We offer sex education with little “love education,” training mechanics rather than creating knights and ladies.

And yet even in this desert of affections, surely the best of marriages includes laughter shared in the bedroom.

The Essentials of the Good Life

Another writer who straddled the Age of Faith and the rebirth of the classics was Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey (circa 1517—1547). Accused of an affair with Henry VIII’s paramour and wife, Anne Boleyn, Thomas Wyatt spent time in prison before regaining the good graces of the king. Howard was less fortunate. An impulsive hothead, he was accused of planning a rebellion against the king and was, in due time, beheaded.

Fascinated by some of the ancient writers, Howard was particularly drawn to the works of Marcus Valerius Martialis, also known as Martial. “The Means to Attain a Happy Life” is his loose and creative translation of one of that Roman poet’s epigrams, a poem that stands in ironic counterpoint to Howard’s wild life:

Martial, the things that do attain

The happy life, be these, I find:—

The richesse left, not got with pain;

The fruitful ground, the quiet mind:The equal friend; no grudge, no strife;

No charge of rule, nor governance;

Without disease, the healthful life;

The household of continuance;

The mean diet, no delicate fare;

True wisdom join'd with simpleness;

The night discharged of all care,

Where wine the wit may not oppress.

The faithful wife, without debate;

Such sleeps as may beguile the night:

Contented with thine own estate

Ne wish for death, ne fear his might.

Readers of this Howard–Martial collaboration can readily discern that the markers for a good life in ancient Rome and Renaissance England loosely match those recommended by today’s therapists and life coaches. A healthy diet, true friends, a loving and loyal partner, and contentment with what we own and who we are remain as pertinent today to our happiness as ever.

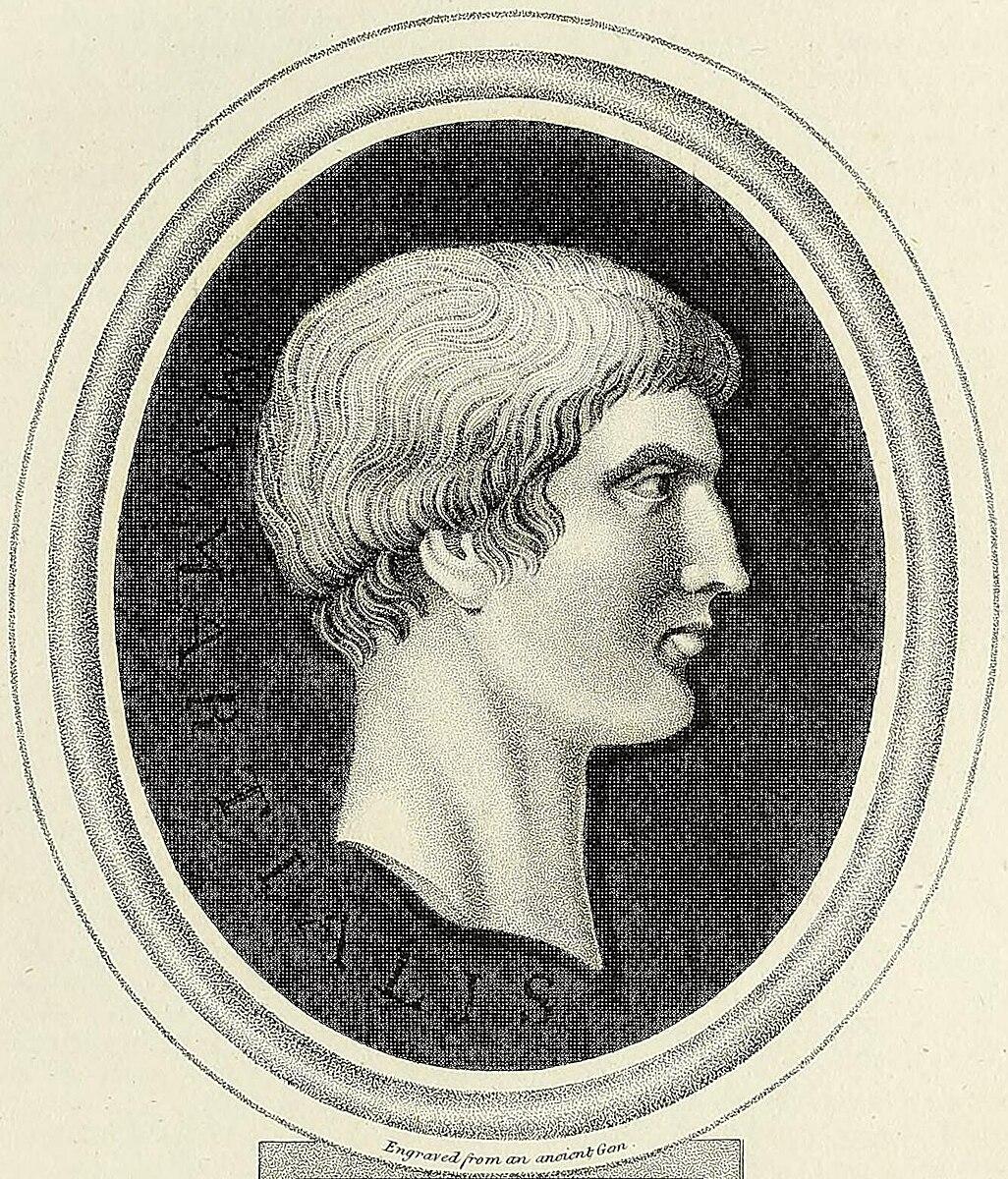

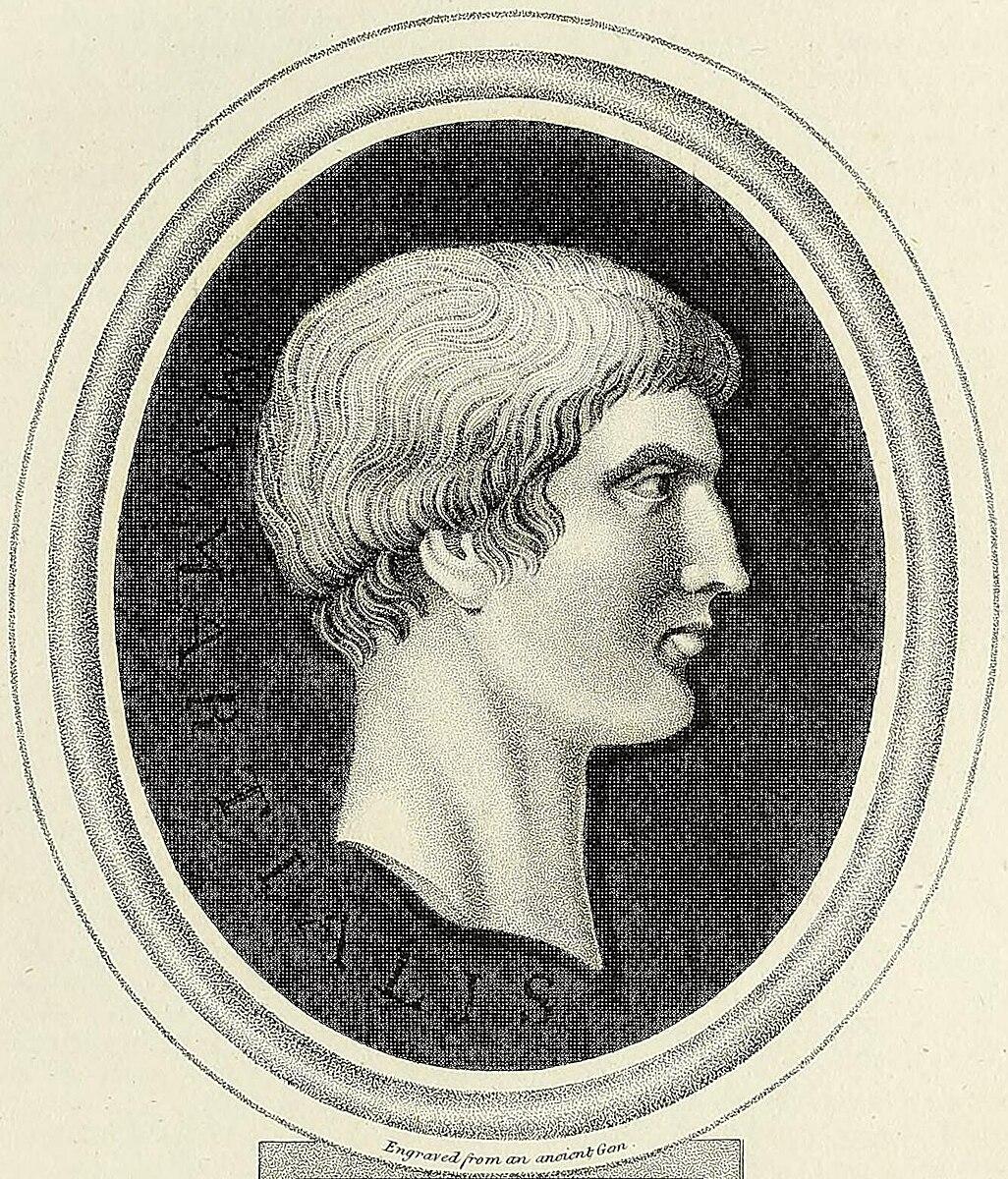

Martial, engraved from an ancient gem, 1816, from the "Encyclopaedia Londinensis: Volume XIV" edited by John Wilkes. (Public Domain)

The Mirror That Works Both Ways

A reader judges a book or a poem, but the wise know that books and verse can also judge the reader.

So it is with history. Many today are quick to pass judgment on people of the past—the ancient Greeks and Romans, the Crusaders, the European explorers, and the Founding Fathers. They mock the men and women of the Middle Ages, for instance, as being ignorant, mired in primitive religious beliefs and superstitions, and ensnared in the chains of an oppressive culture.

Yet in their writings, the men and women of that same bygone epoch implicitly condemn and find laughable some of our modernist views and prejudices: our relativism, our policies regarding abortion, our twisting of language and restrictions on thought, the inability of some among us to define a woman, and an educational system that teaches science, history, literature, and more but forbids mention of a deity.

"Incipit Vita Nova," 1903, by Cesare Saccaggi. This painting depicts Dante and Beatrice together. (Public Domain)

If we read and learn from the poets of the past, we have at hand an antidote to our current plague of presentism. This medicine can make us more fully human in the bargain.

What arts and culture topics would you like us to cover? Please email ideas or feedback to features@epochtimes.nyc