The audacious theft of priceless jewels from the Louvre in Paris on Oct. 19 has been called “the heist of the century” by several local newspapers, and commentators have quickly drawn parallels to similar headline-grabbing crimes over the years.

Questions about security arrangements at the world’s most visited museum, which attracts close to 9 million visitors per year, have been raised in the aftermath of the broad-daylight theft, along with speculation about who could be behind the crime.

As special investigators scramble to catch those involved, here’s what to know about how the heist was pulled off in mere minutes, what was stolen, and why experts fear the jewels may never be recovered.

How It Happened

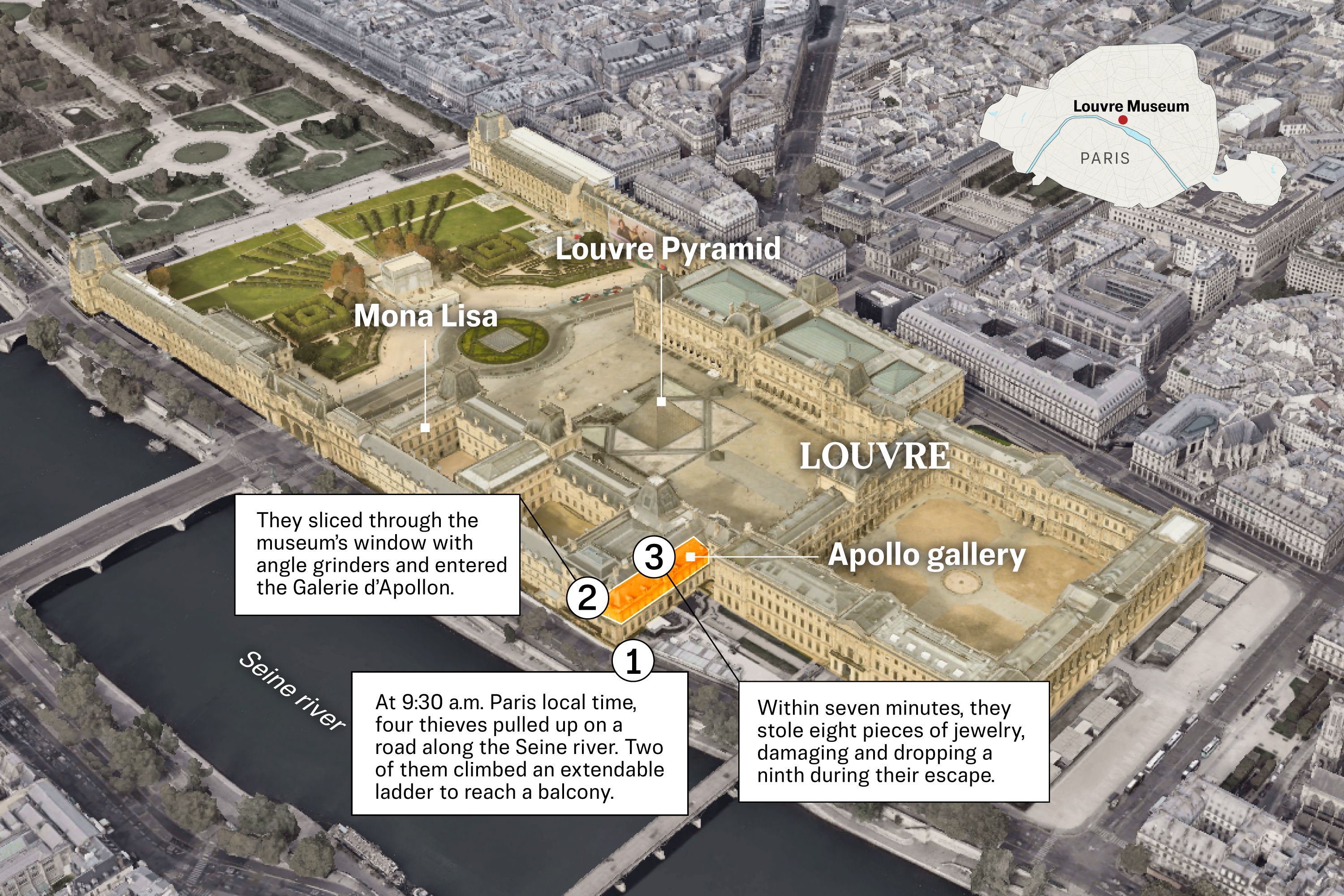

Thieves wearing balaclavas broke into an upstairs gallery on the morning of Oct. 19 using a truck-mounted basket lift known as a “cherry picker” to access an upstairs window before looting precious objects from an area that houses the French crown jewels.

The robbers struck at 9.30 a.m. local time, just half an hour after the museum opened its doors to the public, Paris prosecutor Laure Beccuau told French TV.

They pulled up on a road along the Seine River, climbed an extendable ladder on the cherry picker and broke in through a window of the Galerie d'Apollon building. Although the thieves didn’t carry conventional weapons, they threatened the museum’s guards with the angle grinders they used to slice through the museum’s window, according to Beccuau.

Le Monde and other French media outlets reported that there were four thieves, two of whom wore reflective yellow vests intended to make them look like construction workers. Two rode in the truck, while two were on scooters.

The gang tried unsuccessfully to set fire to the crane as they fled the scene of the crime on motorbikes.

The museum was evacuated as the alarm sounded following the smash and grab, and remained closed through Oct. 20.

French police officers stand next to an extendable ladder used by the thieves to enter the Louvre museum in Paris on Oct. 19, 2025. (Dimitar Dilkoff/AFP via Getty Images)

What Was Stolen?

While nine objects were targeted, eight were successfully stolen. The thieves dropped the ninth, the crown of Napoleon III’s wife, Empress Eugénie, during their escape, the prosecutor said. The piece is adorned with 1,354 diamonds and 56 emeralds, according to the museum’s

website.

Drouot auction house President Alexandre Giquello told Reuters that the auction house would value the crown at “several tens of millions of euros,” noting that in his opinion, it was “not the most important item” in the targeted haul.

The Culture Ministry said the eight stolen items include:

- A tiara from a sapphire jewelry set belonging to Queen Marie‑Amélie and Queen Hortense

- A necklace from the same sapphire set

- A single earring (one half of a pair) from that sapphire set

- An emerald necklace from the jewelry set of Empress Marie‑Louise (Napoleon I’s second wife)

- A pair of emerald earrings from the Marie-Louise set

- A brooch known as the “reliquary brooch”

- A tiara belonging to Empress Eugénie (wife of Napoleon III)

- A large bodice-knot brooch (corsage bow brooch) belonging to Empress Eugénie

Mystery surrounds why the thieves did not also steal the Regent diamond, which is housed in the Galerie d'Apollon and has an estimated value of more than $60 million, according to Sotheby’s.

(Clockwise From Top L) A tiara, a necklace, and a single earring from the sapphire jewelery set of Queen Marie‑Amélie and Queen Hortense. An emerald necklace and a pair of emerald earrings from the jewelry set of Empress Marie‑Louise. A brooch known as the “reliquary brooch.” A large bodice-knot brooch of Empress Eugénie. A tiara of Empress Eugénie. The crown of Napoleon III’s wife, Empress Eugenie. (Stéphane Maréchalle/Musée du Louvre)

Who Could Be Behind It?

Beccuau said in the immediate aftermath of the crime that nothing was being ruled out and that all lines of inquiry were open—although foreign interference was not among investigators’ main hypotheses.

She said it was likely that the robbery was either commissioned by a collector—in which case there was a chance of recovering the pieces in a good state—or carried out by thieves interested only in the monetary value of the jewels and precious metals.

“We’re looking at the hypothesis of organized crime,” the prosecutor said, noting that the culprits could be thieves working on spec for a buyer or seeking jewels that could be used to launder criminal proceeds.

“Nowadays, anything can be linked to drug trafficking, given the significant sums of money obtained from [this crime].”

The probe is being led by a specialized police unit with a high success rate in solving high-profile robberies, according to French Interior Minister Laurent Nuñez.

A French forensics officer examines the broken window on the balcony of the crime scene at the Louvre in Paris on Oct. 19, 2025. (Kiran Ridley/Getty Images)

Why Wasn’t Security Tighter?

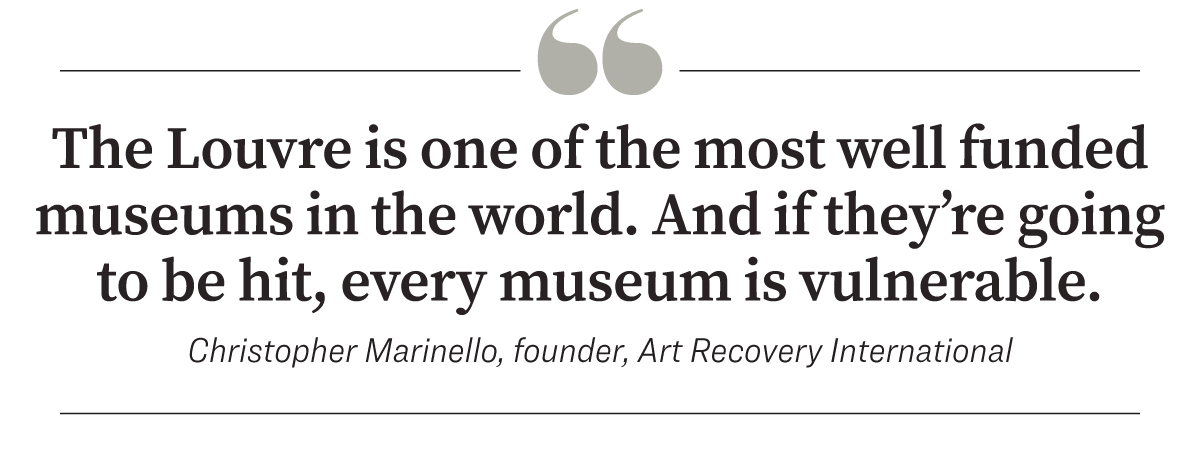

The heist has reignited a debate around funding for museums, which are far less secure than banks, despite being increasingly targeted by thieves.

Earlier this year, officials at the Louvre urgently requested funding from the French government to restore and renovate the museum’s aging exhibition halls and better protect its countless works of art.

French President Emmanuel Macron said on X that a new government plan for the Louvre announced in January “provides for strengthened security.” Despite the French president’s promise of a 700 million euro refurbishment, museum staff went on strike in June over what they said was dangerous overcrowding.

Culture Minister Rachida Dati said on a visit on Oct. 20 to the scene of the crime that the issue of museum security is not new.

“For 40 years, there was little focus on securing these major museums, and two years ago, the president of the Louvre requested a security audit from the police prefect. Why? Because museums must adapt to new forms of crime,” she said. “Today, it’s organized crime—professionals.”

People visit the Galerie d'Apollon at the Louvre in Paris on Oct. 14, 2020. The famous Parisian museum has been targeted by thieves many times in history. (Ludovic Marin/AFP via Getty Images)

Justice Minister Gérald Darmanin said the crime cast France in a “deplorable” light. Opposition politicians criticized the government for what they branded a national humiliation at a time when the country is already deep in political crisis.

Christopher Marinello, founder of Art Recovery International, an organization that specializes in recovering stolen art, said, “The Louvre is one of the most well funded museums in the world. And if they’re going to be hit, every museum is vulnerable.”

France will review the protection of cultural sites across the country and beef up security if needed, officials said on Oct. 20.

Does the Theft Surpass Previous Heists?

This is far from the first theft from the famous Parisian museum, which has been targeted many times, with some of those headline-hitting heists being made into films.

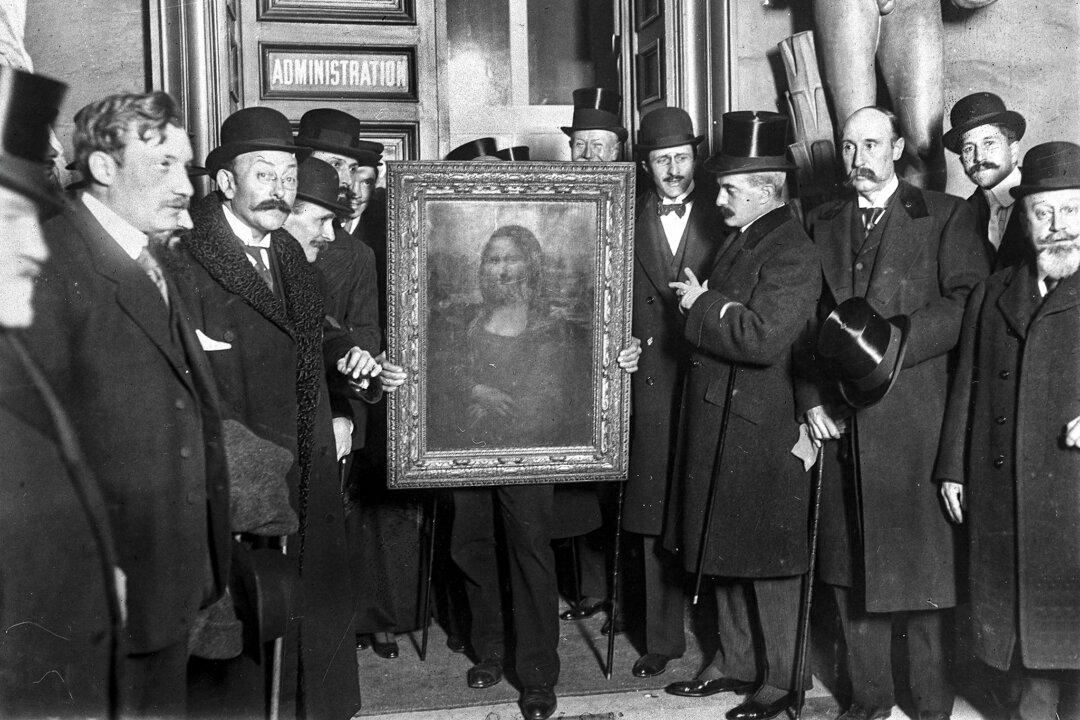

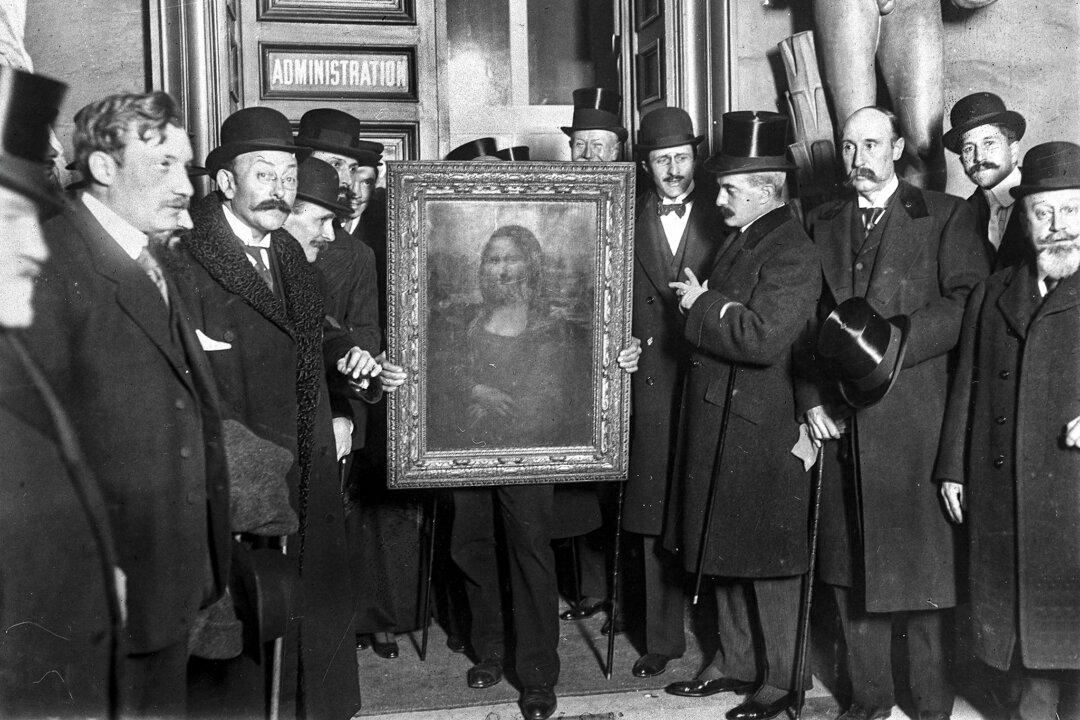

In one of the most famous and daring art thefts in history, the Mona Lisa was stolen from the museum in a 1911 theft carried out by a former employee who had knowledge of the layout and security of the building.

Italian house painter Vincenzo Peruggia dressed as a museum worker to enter the museum and hid in a cupboard overnight, managing to remove the da Vinci masterpiece and sneak out. He kept the artwork in his Paris apartment for two years but was caught and arrested when he tried to sell it.

Peruggia served only seven months in jail after the court judged that he was ideologically rather than financially motivated, believing that the painting rightfully belonged to Italy.

The returned Mona Lisa after it was stolen in 1911, at the Louvre in Paris on Jan. 4, 1914. (Public Domain)

The Oct. 19 heist was the first known theft from the Louvre since 1998, when a painting by French landscape and portrait painter Camille Corot was stolen. That painting is still unrecovered.

Just last month, criminals broke into Paris’s Natural History Museum, making off with gold samples worth $700,000. Also in September, criminals stole a vase and two dishes from a museum in the central city of Limoges, France, with the items valued at $7.6 million

The biggest art heist in U.S. history involved the theft of 13 works from Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. That crime remains unsolved after 35 years.

In the early hours of March 18, 1990, two men disguised as police officers talked their way into the Boston museum before overpowering security guards, tying them up, and going on an 81-minute stealing spree of paintings, including masterpieces by Manet, Rembrandt, Vermeer, and Degas.

Vjeran Tomic, the so-called French Spiderman, stole five never-recovered masterpieces from the Musee D’Art Moderne in 2010 and referred to his crime as “an act of imagination” in an interview with The New Yorker.

Police officers investigate at the Paris' Musee d'Art Moderne, where five works including paintings by Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso have been stolen, on May 20, 2010. The pieces were never recovered. (Bertrand Guay/AFP via Getty Images)

What Will Happen to the Items?

Less than 10 percent of stolen artworks are ever recovered, according to various international estimates.

The artworks have been described by experts as “completely unsellable” in their present form—meaning that they may be broken up and completely reconstructed to make it less risky to put them on the jewels and metal market.

“Ideally, the perpetrators would realise the gravity of their crime and the dimension they’ve entered into, and return the items, since the jewels are completely unsellable,” Giquello told Reuters.

Tobias Kormind, managing director of 77 Diamonds, told The Associated Press: “It’s unlikely these jewels will ever be seen again. Professional crews often break down and re-cut large, recognizable stones to evade detection, effectively erasing their provenance.”

There has been speculation that cryptocurrency could play a part in the crime. British private detective John Eastham said that art-crime investigators are seeing a sharp pivot from cash-based laundering to crypto-based liquidity when stolen goods are difficult to sell openly.

“When a theft involves extraordinary value—particularly heritage items—the real question isn’t just what was taken, it’s how will it be monetized? You can’t simply walk into a bank with millions in notes or diamonds. Crypto offers speed, anonymity, and international reach in a way cash no longer can,” Eastham said in an emailed statement.

“It’s highly likely that whoever is behind the Louvre theft already had a digital exit plan—either melting down components and selling through private networks or using high-value NFTs (Non-Fungible Tokens) or stablecoins to launder the funds.”

Macron, in a post on X, vowed to recover the jewels and bring the perpetrators to justice. He called the theft “an attack on a heritage that we cherish because it is our History.”

Reuters and The Associated Press contributed to this article.