CODORA, Calif.—After facing four years of drought and state-imposed water restrictions, Bruce and Christopher Lopes struggled to save their organic rice farm in northern California’s Sacramento Valley.

The father-and-son duo set out on a mission to reinvent their operations by using new methods to farm rice and milling and selling their own rice for the first time in the farm’s more than century-old history.

They are among the few organic rice farmers in North America trying the Japanese integrated duck–rice farming method to control weeds, conserve water, and fertilize their rice fields without using synthetic nitrogen fertilizers, chemical pesticides, and herbicides.

The Lopeses endured severe drought from 2019 to 2023 and feared that the farm would be lost if the drought dragged into a fifth year.

During the drought, the aquifer and irrigation canal at the farm ran dry.

“We thought we’re going out of business because there was no water for four years, and the insurance was starting to run out. It was terrifying. We thought it was the end of the world,” Christopher Lopes said. “If we would have got one more drought year—game over for half the farms on this side of the valley.”

Bruce Lopes, 68, fell into a deep depression.

With the state’s warnings of perpetual drought and no water allocations for the west side of the Sacramento River in 2020, the duo decided to dig in and drill new wells.

“My bank canceled out on me. My other bank struggled, but we finally got our line of credit,” Bruce said.

Fortunately, they had the last two well permits in the county. They borrowed enough money to pay about $150,000 apiece for the wells and install a new pump and irrigation system for a total cost of nearly $400,000.

They were able to get one of the new wells pumping to avert disaster, and the drought ended the next year. But they knew that they needed to find a new business model if the farm was to survive the next drought.

Christopher, 37, is no stranger to that worry.

“I was told growing up that the farm wouldn’t be here when I was older because we were going to be out of business. My dad said, ‘Go do anything but farming,’” he said.

But Christopher had other ideas. He wanted to save the family farm and since high school has tried to figure out a way to transition the farm so that he can thrive on 60 acres, the amount of land he will inherit.

He said he never told his father of his plan to find a career with flexible hours to support his passion for farming. He became an X-ray and CT scan technician, earning about $80,000 a year at a hospital in Chico.

“I’m doing this for him,” Christopher said, glancing over at his dad, “and all the generations that came before. I want to continue it—not let it die with me.”

Organic rice farmers Bruce Lopes (L) and his son Christopher Lopes (R) load bags of rice into trucks outside Willows, Calif., on Sept. 4, 2025. The Lopes family began experimenting with duck–rice farming in 2021, after years of drought and state-imposed water restrictions nearly forced them to shut down. (John Fredricks/The Epoch Times)

Christopher learned about duck–rice farming about 10 years ago; it was a “light bulb moment” that gave him hope.

He fondly remembers rising with the sun each morning so the 2-day-old ducklings that arrived by mail from the hatchery could imprint on him and then guiding them on the perilous 100-yard journey to the rice fields from the duck shack and pond that the duo had built for them.

Integrated duck–rice farming is based on the symbiotic relationship between ducks and rice paddies. Ducklings, as young as 2 days old, are released into rice fields to eat weeds, insects, and invertebrates that can threaten the crop. The ducklings don’t eat rice plant leaves because they naturally contain silica, giving them an abrasive texture that irritates duck bills.

Chinese farmers raised ducks in irrigated rice paddies to fertilize the soil and control weeds centuries before the advent of synthetic nitrogen fertilizer and chemicals for weed and pest control.

With consumer buying trends moving toward organic foods, some farmers have returned to the methods of old, including integrated duck–rice farming, with a few modern twists.

The aigamo method, used in ancient China and modernized by Japanese farmer Takao Furuno in the 1980s, takes a more modern approach to the ancient ways by using artificially hatched ducklings and modern enclosure systems. Aigamo ducklings are a crossbreed between wild and domestic ducks. They’re used for natural and organic pest control, fertilizer, and weed suppression.

Ducks used by farmers in organic rice production graze together in a pond near crops outside of Willows, Calif., on Sept. 4, 2025. Integrated duck–rice farming relies on the symbiotic relationship between ducks and paddies, helping farmers conserve water, control weeds, and fertilize soil without synthetic chemicals. (John Freddicks/The Epoch Times)

Erik Andrus, a Vermont wheat-and-barley farmer who learned from Furuno in Japan—and in 2010 was one of the first to experiment with duck–rice farming in the United States—became the Lopeses’ mentor, Christopher said.

In traditional organic farming as it is practiced today, rice fields are seeded by aircraft, but that method requires about 300 pounds of seed per acre, a total of about $150 an acre at $50 per 100-pound sack. Instead, the Lopeses transplant rice seedlings, which cuts the amount of seed to 30 pounds per acre and the cost to $15 an acre, Christopher said.

The ducklings can’t maneuver through rice fields that have been planted by aerial seeding, he said.

Instead, the Lopeses learned the Japanese method of growing the rice plants in trays and attaching the transplanter to a tractor to plant the rice seedlings precisely in a grid pattern that creates channels, allowing the ducklings to move freely between rows.

The rice is grown in a 4,000-square-foot area in inch-deep trays; about 100 trays per acre are needed. This year, the Lopeses planted 25 acres of duck rice.

“With the transplanter, we’re able to basically give the ducks more room in the field, because it plants about 10 inches in between each plant and a foot in between each row,” Christopher said.

That allows the ducks to get close to the plants and eat the weeds and insects that could harm the rice crop.

(Top) Ducklings eat the weeds in the organic rice fields at Lopes Family Farms in California’s Sacramento Valley. (Bottom) Rice is planted in trays to be transplanted into the organic duck–rice fields at the Lopes Family Farms near Codora, Calif. (Courtesy Lopes Family Farms)

“We use 10 times less seed to do the same amount of acreage,” Christopher said.

Transplanting also results in healthier plant growth and higher yields per plant, Bruce said.

Because rice plants are resilient to flooding, in traditional organic rice farming, fields are flooded with water to drown out weeds and eliminate labor-intensive manual weeding.

But in duck–rice farming, the ducklings do the weeding and cut water usage by about two-thirds, Christopher said.

“We normally have 10 inches of water in this field,” Bruce said. “If those weeds make it through at the same time the rice does, it’s over.”

When the ducklings are released, they treat the rice as their habitat instead of their food, and the plants help shelter them from predatory birds, he said.

The ducks’ activity in the rice paddies aerates the water, creating more dissolved oxygen and disrupting photosynthesis as they muddy the water, which blocks the sunlight to prevent weed growth. The ducks eat the weeds that have already surfaced and bugs, snails, and worms that are destructive to the rice crop, and their manure puts nitrates back into the soil.

“They just take care of everything,” Bruce said.

This year, the Lopeses released about 700 Muscovy ducklings, but they’ve learned that Muscovy ducks are harder to train and don’t seem to have the same foraging instincts as Pekin ducks, which they had used in the past.

The Muscovy ducks, Christopher said, are more of a wood duck and are less apt to be in the water than Pekins.

(Top) Organic rice farmer Christopher Lopes prepares to enter crop areas in Willows, Calif., on Sept. 4, 2025. (Bottom Left) Rice crops sit in pools of water in Willows, Calif., on Sept. 4, 2025. (Bottom Right) Ducks used by farmers in organic rice production graze together near crops outside of Willows, Calif., on Sept. 4, 2025. (John Fredricks/The Epoch Times)

By the time the rice goes to seed, the ducks are removed from the rice fields—usually at about eight to nine weeks—so they don’t destroy the rice crop, Christopher said.

“So they’re not eating the rice,” he said. “They don’t see the rice seed ever.”

Larger mature ducks can wreak havoc on a rice crop, turning from hero to villain if left too long in the fields. They will not only eat the rice but will also fly, land on the plants, and trample them, Christopher said.

In addition, the ducks must be removed from the rice fields 90 days before harvest for food safety reasons to comply with Department of Agriculture regulations, he said.

The ethically raised free-range ducks then become a secondary crop that goes to restaurants, Christopher said.

A Labor of Love

The Lopeses began their experiment with duck–rice farming in 2021.

The first batch of 180 ducklings arrived at the farm that May, about two months before the transplanting equipment they had ordered from China. By then, it was too late in the season to plant, so they raised the ducks and donated them to relief kitchens for firefighters and people displaced by wildfires.

It wasn’t until 2022 that the Lopeses had their first successful crop of rice farmed with the new method.

Designing the duck pond, irrigation system, and rice fields, and building levees hasn’t been easy, nor has learning how to use new equipment and train the ducklings.

They have learned by trial and error, have had to find creative solutions to problems along the way, and have never given up on their dream.

One season, they lost 100 ducks to coyotes.

“There is no quitting. You just figure it out on the fly all day long,” Christopher said.

He calls it “failing forward” toward success.

For both father and son, farming is a labor of love.

Bruce said he earns about $25,000 a year in profits from the farm.

“I make about $5 an hour,” he said. “I love feeding the people, so I just keep on going. It’s the only thing I know.”

Bruce said he’s proud of Christopher’s research, hard work, and stick-to-itiveness, which have helped breathe new life into the farm to make it more sustainable.

The new method is innovative and exciting and has given him a renewed zest for life, he said.

“I’ve been growing organic rice for 24 years and selling it for pennies on the dollar, and then he came up with the duck–rice method. It just changed my entire life,” Bruce said. “There are no words for it. I’m just a whole new person.”

Organic rice farmer Bruce Lopes looks at samples of his crops in Willows, Calif., on Sept. 4, 2025. (John Freddicks/The Epoch Times)

Christopher, too, said duck–rice farming has changed his relationship with the land.

“You change as a human being,” he said.

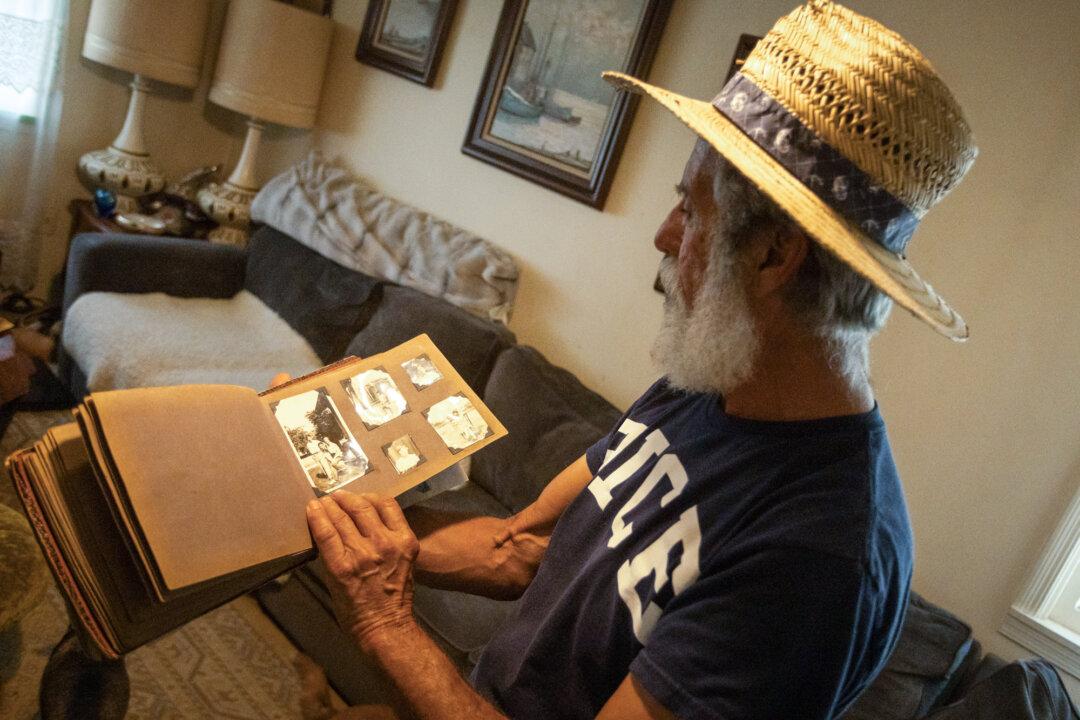

Deep Roots in Farming

The Lopes family has been growing rice for four generations at the farm, which is located on a natural floodplain. The farmhouse was built on stilts before the construction of levees on the Sacramento River was completed.

Bruce’s grandfather, John Sylvester Lopes, founded the rice farm in 1914. He emigrated from the Azores island of São Jorge, Portugal, in 1899 with the clothes on his back, two loaves of bread, and very little money. When he disembarked from the ship at the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor, he couldn’t speak English but managed to find work and earn enough money to travel by wagon train to the foothills of Winnemucca, Nevada, where he met his wife, Mary, also an immigrant from São Jorge.

Lopes raised sheep, but they were stolen by other ranchers in the area, his grandson said. And although he went to court and won the lawsuit, the judge warned him that the other ranchers were looking for trouble and suggested that he leave Winnemucca, Bruce said.

The couple journeyed across Donner Pass, eventually arriving at the Point Reyes peninsula in Northern California, where Mary had relatives. There, they worked until they’d saved enough money and settled in nearby Codora in 1910 to start rice farming.

John and Mary’s son Charles inherited the farmhouse and 203 acres of land. He formed a partnership with his sons Richard, Larry, and Bruce in 1967. In 2001, the farm was certified organic.

Bruce said he is thankful that he was blessed with grandparents who enjoyed a simple life of hard work and built the rice farm, a big change from sheep herding but a success.

He said his father, Charles, and his mother, Rose, provided their children with a comfortable upbringing, good food, and a clean set of clothes for Sundays. They taught him to “give when you can, help when you can, and always leave people feeling better than when they arrived.”

Organic rice farmer Bruce Lopes reviews old photographs in Willows, Calif., on Sept. 4, 2025. (John Freddicks/The Epoch Times)

A Heritage of Hospitality

The family was known for its generosity and hospitality during the Great Depression. The Dirty Thirties brought many destitute people without jobs—or “hobos,” as they were known—from drought-stricken farms in the U.S. Midwest and big cities in the East after the stock market crashed on Oct. 28, 1929.

Mary Lopes, known affectionately as Vovó—Portuguese for grandma—served meals to the hobos who rode the rails to California in search of work. She would look out the window and see them approaching the farm, Bruce said.

Word of such hospitality spread fast, and the engineers would stop the train on the tracks near the farm.

“Hospitality started with grandma, with Vovó. She loved to cook and help people,” Bruce said.

She would ask Bruce’s mother to get a chicken from the barn, and by the time the hungry dinner guests arrived, Rose had it plucked and ready to roast.

But many of the hobos were too proud to accept a free meal without earning it, so Vovó would give them a few chores, such as chopping firewood or weeding the garden, to do before dinner.

“They weren’t looking for a handout. They wanted to work,” he said. “The meal was just part of it. We would pay them and then send them off on their way.”

Bruce carried on the tradition of offering home-cooked meals to those in need. And sometimes, those who needed a little extra help would end up back at the farm.

A photograph of Mary Lopes, grandmother of Bruce Lopes, overlooks organic rice fields in Willows, Calif., on Sept. 4, 2025. Immigrants from São Jorge, Portugal, Mary and her husband, John Sylvester Lopes, founded the farm in 1914. (John Fredricks/The Epoch Times)

“I’d be in town. I’d bring them back,” he said.

“I believe everybody that’s in your life is there for a reason. I’d bring people over that couldn’t hold jobs, didn’t have food—just people that I’d met in Chico or in Willows, or even my friends back when we were younger.”

In line with that philosophy, Lopes Family Farms continues to give back to the community, donating rice for community fundraisers and to fire victims in Los Angeles. The family is well-known at the local farmers market, where Bruce welcomes hugs from his customers.

Christopher arranged to sell rice farmed with the duck–rice method to California schools through the state’s Farm to School program.

“That’s everything for me,” Bruce said, holding back tears.

Children, he said, need the protein and carbohydrates that rice provides to grow up strong and healthy.

“I want to feed the kids of California duck rice because it’s the best rice ever,” Bruce said.

Last year, foreign exchange students in the Future Leaders Exchange program, sponsored by the State Department, began tours of Lopes Family Farms.

The Lopeses said they are grateful for the Chico community, including local restaurants that put their ducks and rice on their menus, and people who have advised them and helped them market their Ducks N’ Rice products.

Sawtelle Sake, a sake brewery in Los Angeles, sources all of its sake rice from the Sacramento Valley. It recently partnered with Lopes Family Farms for its organically grown duck rice. Sawtelle describes the process as “a truly radical and mindful approach to rice cultivation” that produces “exceptional” rice.