Something particular stood out about Timothy Matlack. Indeed, there were many things, like the fact he loved to gamble, engaged with the lower and ruffian classes, and brawled whenever necessary (and sometimes seemingly when it wasn’t), all while being a Quaker. Certainly these characteristics stood out, but it was actually his writing style that would ignite his rise to prominence. It wasn’t his rhetoric, though, but rather the “looping flourishes” and the elegant style of his penmanship.

Matlack (1736–1829) was born in Haddonfield, New Jersey, into a family of Quakers. His father made a living as a merchant and brewer. A decade after his birth, the family moved to Philadelphia, where this revolutionary firebrand would find his place among a hotbed of revolutionaries.

"Timothy Matlack," circa 1790, by Charles Wilson Peale. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. (Public Domain)

Rough Times

The young Quaker learned the business trade and earned money on the side, as well as a less than upstanding reputation by way of betting on horse races and cockfights. When he was 13, he signed his first contract as an apprentice for a local Quaker merchant. His signature demonstrated an elegance that was rather in opposition to his rough personality. Shortly after this contract was signed, however, his family experienced immense hardship. His father’s debts resulted in the family’s brewery and much of their household goods being seized by the courts. A legal agreement did salvage the use of the brewery, but it would not be Matlack’s father in charge; it would be his elder half-brother. The humiliation proved too much for his father, who subsequently drank himself to death.

As his half-brother continued with the brewery and his younger brothers were sent to a school for charity cases, Matlack continued his apprenticeship, completing it in 1758. That same year he married Ellen Yarnall, the daughter of a Quaker preacher. At this time, the Americans were in the middle of the French and Indian War. In 1759, Benjamin Franklin, who was arguably Philadelphia’s most famous citizen, printed the Pennsylvania Assembly’s petition to King George II about the Native Americans. Franklin, aware of Matlack’s writing ability, hired him to pen the petition. It would not be his last such project.

The following year, Matlack opened his own business selling fabrics and hardware. His affinity for gambling, however, led him to financial ruin. He was tossed into debtor’s prison but was redeemed by several wealthy Quakers. Despite this example of Christian charity, the Quakers viewed Matlack as a problem for the religious community. In 1765, Matlack was disowned by the Society of Friends.

Rebound and Revolution

In many ways, Matlack didn’t reflect the views of hi

s fellow Quakers. He also ridiculed Quakers who remained in the Society yet owned slaves—Quakers were known for their stance of antislavery. His sharp criticisms seems to have expedited his removal from the community.By this time, the French and Indian War had been over for two years, and Great Britain, and therefore its American subjects, had been under the rule of a new king, George III, for five years. When the war ended in 1763, the king and British Parliament in London believed it necessary to tax the Americans without their consent in order to pay off the immense war debts. Thus, the British enacted the Sugar Act of 1764. The slow, but steady political upheaval that led to the American Revolution put Philadelphia, as well as Matlack, at its center.

Timothy Matlack's careful hand at writing benefited him in more ways than one. (William Booth/Shutterstock)

While Matlack had earned a poor reputation among the Quakers, he had earned a favorable reputation among political radicals. He not only proved affable in their company, but also thoughtful in terms of American liberty.

Matlack spent time in Philadelphia’s alehouses and taverns consorting with fellow republicans. Additionally, his financial situation improved sometime after his removal from the Society of Friends. His half-brother had turned the family business into the city’s largest brewery, and Matlack built off this success with his own brewery and beer bottling operation.

Over the intervening years between 1765 and 1774, Matlack ran his business, continued his gambling and cockfighting, and delved deeper into the growing revolutionary cause. His involvement in each met with success, and his popularity in Philadelphia grew.

Petition and Commission

The Sugar Act of 1764 was just the first of a number of taxes and laws placed on the colonists, who viewed them unconstitutional. On Sept. 5, 1774, delegates from 12 of the 13 colonies assembled in Philadelphia at Carpenter’s Hall to discuss their problems with Parliament. At the time, they believed the king was the solution, not the source of the pr

oblem. By the end of the session, the Congress had written “The Petition of the Grand American Continental Congress, to the King’s Most Excellent Majesty,” in order “to obtain redress of grievances and relief.” Matlack was asked to create two copies of the petition, which he completed by the following day on Oct. 26. It also happened to be the last day of the First Continental Congress’s session. The copies were signed, and one was sent to Benjamin Franklin, who resided in London at the time. Franklin was charged with presenting the petition to Parliament. Parliament and the king duly ignored the petition.

With no redress, tensions increased, resulting in the “shot heard round the world” in April 1775. The American Revolution had begun in earnest and Matlack was fully behind it. By the time the Second Continental Congress assembled, he became an intricate part of it. He wasn’t a delegate, but a clerk for Charles Thomson, the secretary of the Second Continental Congress. His writing skill proved invaluable.

On June 15, 1775, Congress chose George Washington to become commander in chief of the Continental Army. It fell to Matlack to write the formalized version of the commission.

"The Shot Heard Round the World," 2009, by Domenick D'Andrea. (Public Domain)

Penning the Declaration

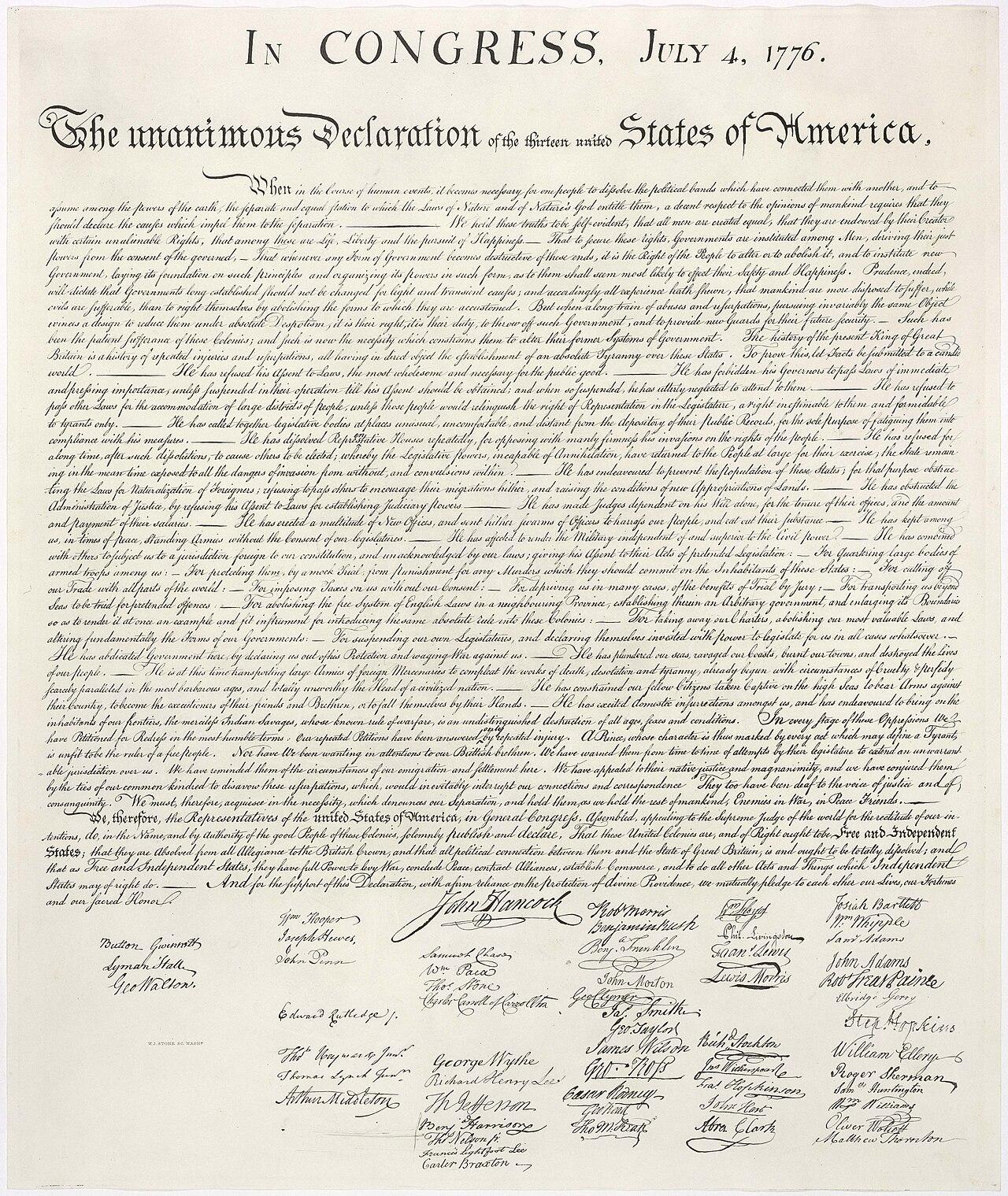

His greatest printing achievement remained a year away, when the delegates of Congress chose to declare their independence from Great Britain. Thomas Jefferson had written the Declaration of Independence and it was edited by

a committee of five—Franklin, John Adams, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston. Members of Congress edited it further, but Matlack created

the version with which the

world would become most familiar.On July 19, 10 days after New York agreed to independence, Congress commissioned Matlack to create an official version of the declaration that every member of Congress could sign.

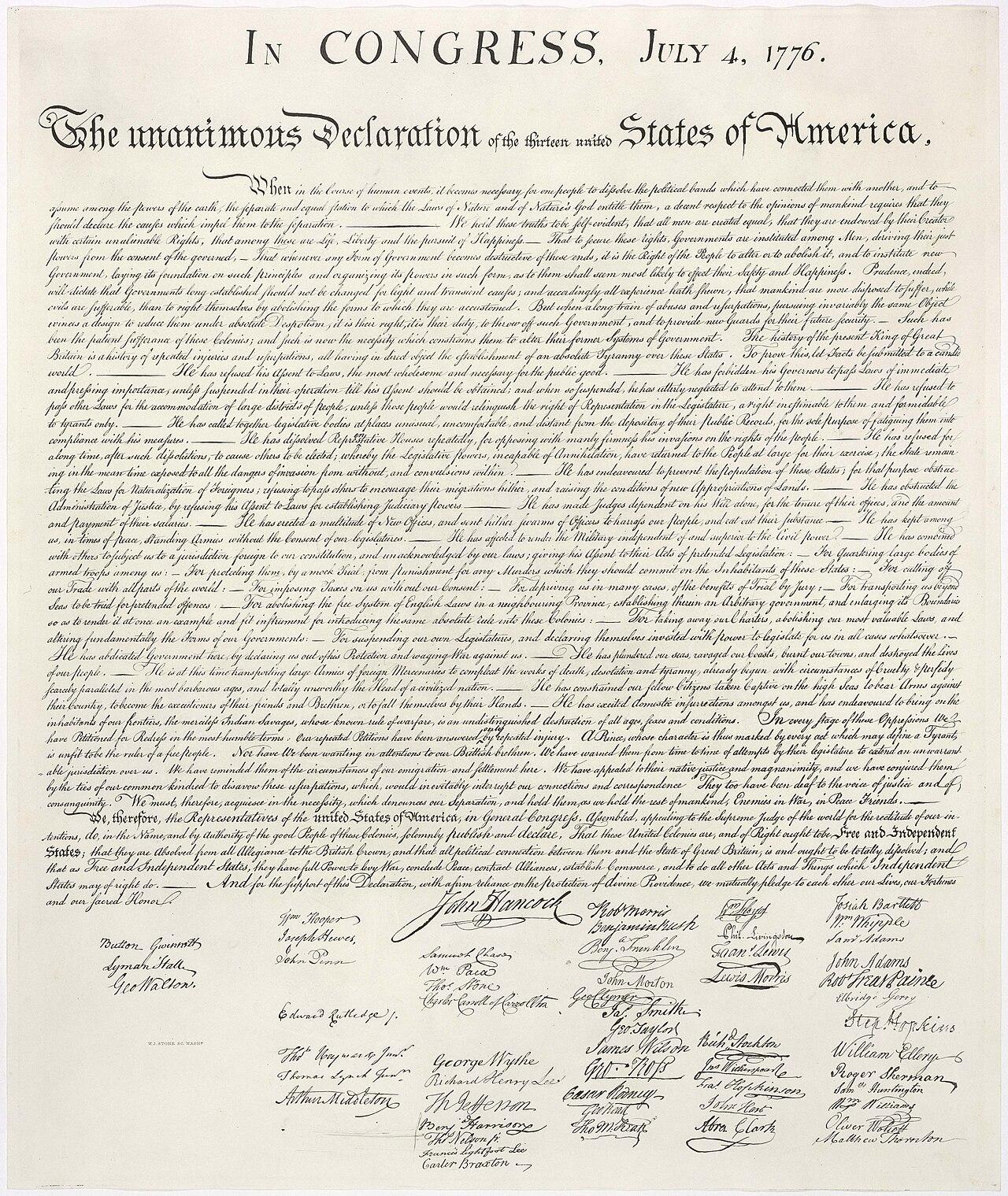

Utilizing the “looping flourishes” and elegant penmanship he had become known for, Matlack penned the Declaration of Independence, and included a new title to it, which read, “The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America.” It is Matlack’s version that has long resided in the rotunda of the Capitol building in Washington where approximately 1 million people come to visit each year.

Although this image is of an 1823 copy of the Declaration of Independence, Matlack's penmanship was preserved. (Public Domain)

Matlack enjoyed a long career in the Revolution as a militia commander, a member of Pennsylvania’s committee of inspection, secretary to Pennsylvania’s Supreme Executive Council, a director of the Bank of North America from 1781–1782, a trustee of the University of Pennsylvania in 1779, a delegate to the Second Continental Congress in 1780, and, interestingly, a founding member of the Society of Free Quakers in 1781. But it was his ability with the pen that cemented his most lasting legacy.

What arts and culture topics would you like us to cover? Please email ideas or feedback to features@epochtimes.nyc