For months, the U.S.–China tariff fight has looked quieter on the surface—fewer headlines, more talk of “stabilizing” ties. However, the pressure on China’s trade model has only widened.

More governments are tightening trade defenses against China in ways that are broader, more coordinated, and more focused on the structure of supply chains.

Instead of focusing on finished goods, nations are increasingly targeting intermediate goods and pathways that enable Chinese products to reach their markets via third countries, experts told The Epoch Times.

They say a structural trend is taking shape—one aimed at containing China’s overcapacity and trade imbalance—and it could do lasting damage to China’s export-led economy.

“I don’t see anything that Beijing can do to reverse this trend,” U.S.-based economist Davy J. Wong told The Epoch Times.

“Beijing’s usual tactics, such as retaliatory measures, can generate short-term leverage but often accelerate de-risking and decoupling efforts by trading partners, limiting their long-term effectiveness.”

Mexico’s actions are the clearest sign yet that the perimeter is expanding beyond the United States, Wong said.

Reducing Workarounds

Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum’s administration earlier this month legislated new tariffs of up to 50 percent on more than 1,400 imports from countries without a free trade agreement with Mexico, including South Korea, India, Vietnam, Thailand, and, particularly, China.

Mexican lawmakers approved the measures on Dec. 10 across sectors such as textiles, steel, iron, automotive parts, and plastics. The tariffs are set to take effect in 2026.

Beijing criticized the move as running against globalization. Sheinbaum framed it as industrial policy—supporting domestic industries such as autos and textiles—while saying Mexico is not seeking a trade war.

Mexico is the largest U.S. trading partner, and its factories have become a key route for companies seeking access to the U.S. market while reducing direct exposure to U.S.–China tariffs.

Mexico’s decision threatens to narrow that workaround as U.S. restrictions tighten, said Frank Tian Xie, a business professor at the University of South Carolina–Aiken.

He told The Epoch Times that the United States and its partners are moving away from one-off duties on finished goods toward “a layered system” that targets subsidies, overcapacity, and—most crucially—the intermediate goods and rules of origin.

That shift is where China’s export model faces its toughest test, Xie said.

Xie attributed Mexico’s latest tariff move to significant pressure from the Trump administration and the upcoming review of the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA) in July 2026.

Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney (L) and Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum hold a joint news conference at the National Palace in Mexico City, Mexico, on Sept. 18, 2025. U.S. Trade Representative Jamieson Greer has said Mexico and Canada should not serve as export hubs for Chinese and other Asian goods. (Yuri Cortez/AFP via Getty Images)

Wong said Mexico has incentives to move early to avoid harsher U.S. demands later. He noted that, as the second-largest U.S. trading partner, Canada may soon face similar pressure to tighten controls tied to China.

U.S. officials have been explicit about the goal.

On Dec. 4, U.S. Trade Representative Jamieson Greer said Mexico and Canada should not act as export hubs for products from China and other Asian countries, tying the issue to USMCA enforcement.

Wong said the 2026 USMCA review gives Washington significant leverage because Mexico and Canada rely on the agreement to preserve access to large parts of the U.S. market.

He said U.S. demands fall into three categories: tighter rules of origin, including higher regional content thresholds and narrower definitions of core components; stronger enforcement, with more frequent audits and tougher penalties; and limits targeting “countries of concern,” restricting how inputs from non-market economies can count toward regional content in sensitive sectors.

Canada, EU Also Tighten Rules

Canada has so far avoided imposing an across-the-board tariff wall on Chinese goods but has taken action in key strategic sectors.

Ottawa had already imposed a 100 percent surtax on Chinese-made electric vehicles and a 25 percent surtax on Chinese steel and aluminum starting in October 2024. It added steel tariff-rate quotas that trigger a 50 percent surtax above quota levels in July.

Wong said the effect is to make origin claims harder to game.

Europe has taken a similarly layered approach.

China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi (R) walks behind French President Emmanuel Macron to his vehicle at Capital International Airport in Beijing on Dec. 3, 2025. Macron said earlier this month that Europe could be forced to take “strong measures,” including tariffs, if Beijing does not address the EU’s widening trade imbalance with China. (Ludovic Marin-Pool/Getty Images)

In October 2024, the European Union imposed definitive additional duties on Chinese battery-electric vehicles following an anti-subsidy probe, raising the combined tariff burden in some cases to roughly 45 percent when added to the EU’s standard car tariff.

The EU is also tightening low-value import channels, a move that mirrors U.S. actions.

EU member states this month agreed to a three-euro ($3.52) customs duty on e-commerce parcels valued at less than 150 euros ($175.82), effective on July 1, 2026, after imports surged in 2024 to 4.6 billion parcels—about 90 percent from China.

French President Emmanuel Macron told business outlet Les Echos on Dec. 7 that Europe could be forced to take “strong measures,” including tariffs, if Beijing does not address the EU’s widening trade imbalance with China. The EU had a trade deficit of 300 billion euros ($335 billion) with China in 2024.

Across Asia, countries such as South Korea, Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, and India have also imposed product-specific anti-dumping duties on certain Chinese steel and steel-related imports.

Wong said China’s “export escape route” is narrowing on three fronts: direct exports face higher barriers; indirect routes are being more tightly policed as Washington pressures Mexico and Canada not to serve as a back door; and low-value consumer channels are tightening because of tougher U.S. enforcement and new EU fees on small parcels.

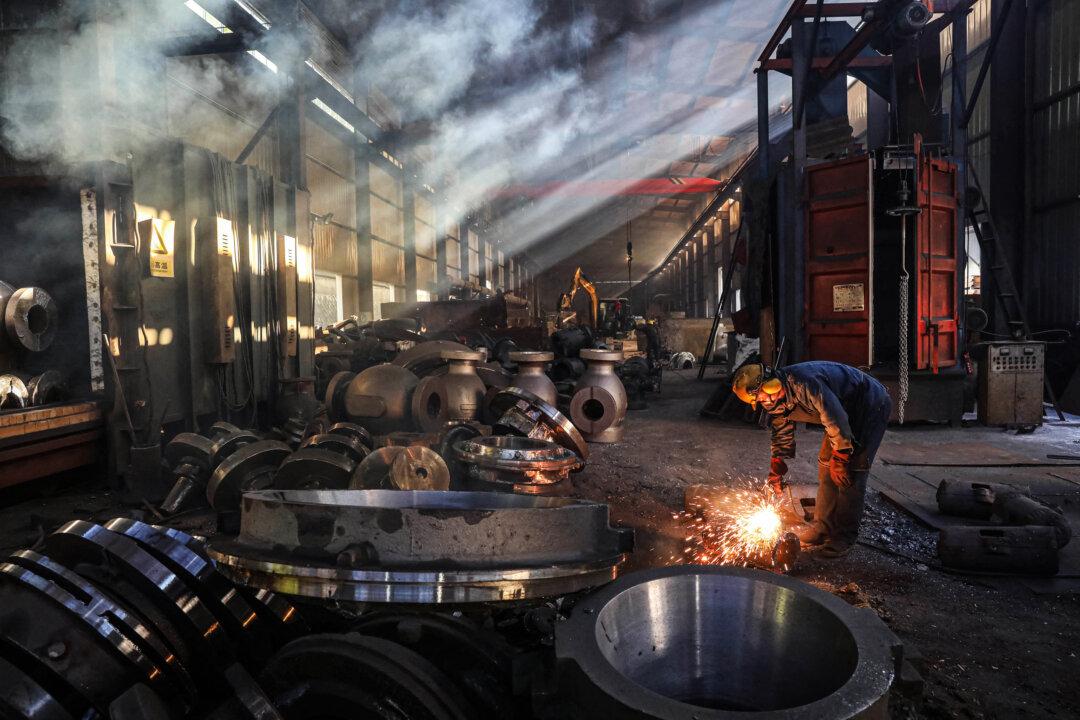

An employee works at a steel machinery factory in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, China, on June 6, 2025. (STR/AFP via Getty Images)

Intermediate Goods the Real Battleground

Wong said many people picture tariff evasion as illegal relabeling, but that is not always the most valuable channel—and it may be less common than people assume.

The deeper issue, he said, is Chinese intermediate goods—inputs that can be “legal, structural, and harder to police.”

Intermediate goods are the inputs used in production: circuit boards, motors, wiring harnesses, battery chemicals, steel coils, fasteners, castings, textiles and fabric, plastic resins, and thousands of other components.

Wong said that policymakers, such as those in Mexico, are increasingly focusing on these inputs, as they help define what counts as “North American” production.

A recent Brookings Institution analysis found that even as direct U.S. imports from China fell by 37.6 percent from 2018 to 2024, China’s intermediate-goods exports to Mexico roughly doubled between 2020 and 2022, and Chinese intermediate-goods exports to Canada rose by 80 percent over the same period.

The report also estimates that about half of trade within North America consists of intermediate products.

“This matters because origin rules focus on where transformation happens, not where every screw and circuit board comes from,” Wong said.

Under trade agreements, a product assembled in Mexico or Canada can enter the United States on preferential terms if it meets the rules of origin—often based on regional value content, tariff classification changes, and tracing requirements, especially in autos.

That is why, according to Wong, an “export hub” pattern often looks like this: Chinese suppliers ship subassemblies and materials—such as electronics modules, wiring harnesses, battery inputs, auto parts, steel inputs, and textiles—to Mexico or Canada.

A factory then completes final assembly or adds a meaningful processing step, he said, and the finished product enters the United States as a Mexican or Canadian export—sometimes fully compliant, sometimes supported by thin paperwork, and sometimes shielded by opaque supply chains.

Measured direct transshipment through Mexico has likely not exceeded about 1.5 percent of Mexican exports to the United States since the tariff implementation in 2018, according to a January study published by the University of California–San Diego.

In plain terms, Wong said, even if the final product is legally “made in Mexico,” a meaningful slice of the value—and a large share of key components—can still originate in China.

A worker checks a machine at a factory producing silk cloth in Fuyang, Anhui Province, China, on April 16, 2025. Economist Davy J. Wong said the deeper issue in China’s tariff evasion involves Chinese intermediate goods used in production in a third country—inputs he described as “legal, structural, and harder to police.” (STR/AFP via Getty Images)

Can Enforcement Work at Scale?

Both Wong and Xie said enforcement represents the stage at which policy objectives face practical constraints.

Wong said the most effective way to increase scalability is to strengthen accountability in the United States, rather than attempting to monitor thousands of factories overseas.

Importer-of-record liability matters, he said, because importers operate under U.S. law. That makes it easier to impose fines, retroactive duties, and reputational damage than to chase foreign suppliers.

Xie said broad factory inspections and end-to-end supply-chain verification are often too costly and difficult at scale, especially when supply chains span many countries.

He said the more realistic deterrent is “retrospective enforcement,” including regular audits that flag abnormal trade patterns—such as sudden surges or unusually large surpluses in specific product categories—followed by retroactive investigations and stiffer penalties when circumvention is found.

Market May Split

Xie said tighter trade defenses will increasingly land on the entire production chain, not just the final product.

Even when assembly shifts abroad, he said, Chinese companies can still lose volume if the upstream input pipeline is targeted. Buyers may also demand non-China sourcing to reduce compliance risk, potentially compressing margins for suppliers tied to China-linked components.

Over time, Xie said, the incentive is to move more production—and more upstream stages—offshore, not just final assembly.

If Mexico’s move is part of a broader wave, Wong said the outcome is unlikely to be a clean “decoupling,” but a two-track system.

On one track—North America, Europe, and countries tightly linked to their supply chains—Chinese goods may still enter but under tougher conditions, including greater compliance requirements, stricter origin checks, fewer loopholes, and higher barriers in strategic sectors.

On the other track—much of the developing world, such as Latin America, Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and Africa—Chinese goods could become more dominant through competitive pricing, and many governments will hesitate to cut off low-cost supply.

Wong noted that this can export deflation into more open markets and squeeze local producers.

Workers load goods for export into a container at a logistics hub in Yiwu, Zhejiang Province, China, on April 29, 2025. (Kevin Frayer/Getty Images)

China’s Likely Response

Wong said the Chinese regime’s retaliation tends to be selective—targeting politically sensitive sectors while leaving room for negotiation.

Europe provides a recent example. In response to the EU’s electric vehicle measures, Beijing leaned on trade-remedy tools, including probes and duties on products such as brandy, pork, and now dairy.

China’s latest move—to impose provisional duties of up to 42.7 percent on certain EU dairy products—has been widely viewed as part of that retaliation cycle.

For Mexico, Xie said Beijing’s levers are narrower because Mexico sells far more to the United States than to China. In his view, China’s most realistic tools may be investigations, World Trade Organization litigation, and administrative friction, none of which will pose an immediate threat.

Wong said Beijing’s options for slowing the broader trend are limited and come with significant trade-offs.

Cutting subsidies or curbing excess capacity would address accusations of state support and overproduction, but he said those steps are politically and economically difficult amid slower growth in China.

Boosting domestic consumption would reduce reliance on exports, but Wong said it would require deeper reforms in income distribution, social security, and housing—and would take time.

Retaliation, he said, can generate short-term leverage but often accelerates de-risking and decoupling by trading partners.

“There is no good solution for Beijing to reverse this trend,” Wong said.

China Exposed

China can redirect exports to other regions, and it already has.

A December Reuters investigation described how Chinese automakers—facing weakening domestic demand for gasoline cars as the electric vehicle transition accelerates—have pushed more vehicles into emerging markets, extending competitive pressure outward even as Western barriers rise.

However, Xie said China’s domestic constraints mean those markets can only absorb so much, limiting how far exporters can offset tighter access to advanced economies.

China has struggled for years to increase household consumption.

Rhodium Group has estimated that China’s household consumption remains around 39 percent of gross domestic product—well below the 54 percent average among Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development countries—making it harder to replace external demand with domestic spending.

An aerial view of apartment buildings developed by the China Evergrande Group in Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China, on Aug. 13, 2025. Rhodium Group has estimated that China’s household consumption percentage of GDP remains well below OECD countries—making it harder for China to replace reduced external demand with domestic spending. (STR/AFP via Getty Images)

Wong said China’s widening property slump has also weighed on consumer confidence and spending.

“Imagine your property value suddenly fell by 50 percent—would you still feel confident spending?” he said, describing what he sees as the psychological hit many households have felt since China’s housing downturn began in mid-2021.

With weak domestic confidence, Wong said China faces a tighter squeeze than a consumption-led economy would.

Amid the current trend, he noted that Chinese exporters may be forced to accept thinner margins, shift more production offshore to meet origin and input rules, or redirect sales to emerging markets that cannot easily replace demand from the United States and Europe.

Gu Xiaohua contributed to this report.