The U.S. Supreme Court ruled 5–4 on March 4 that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) wastewater discharge permitting system violates federal law.

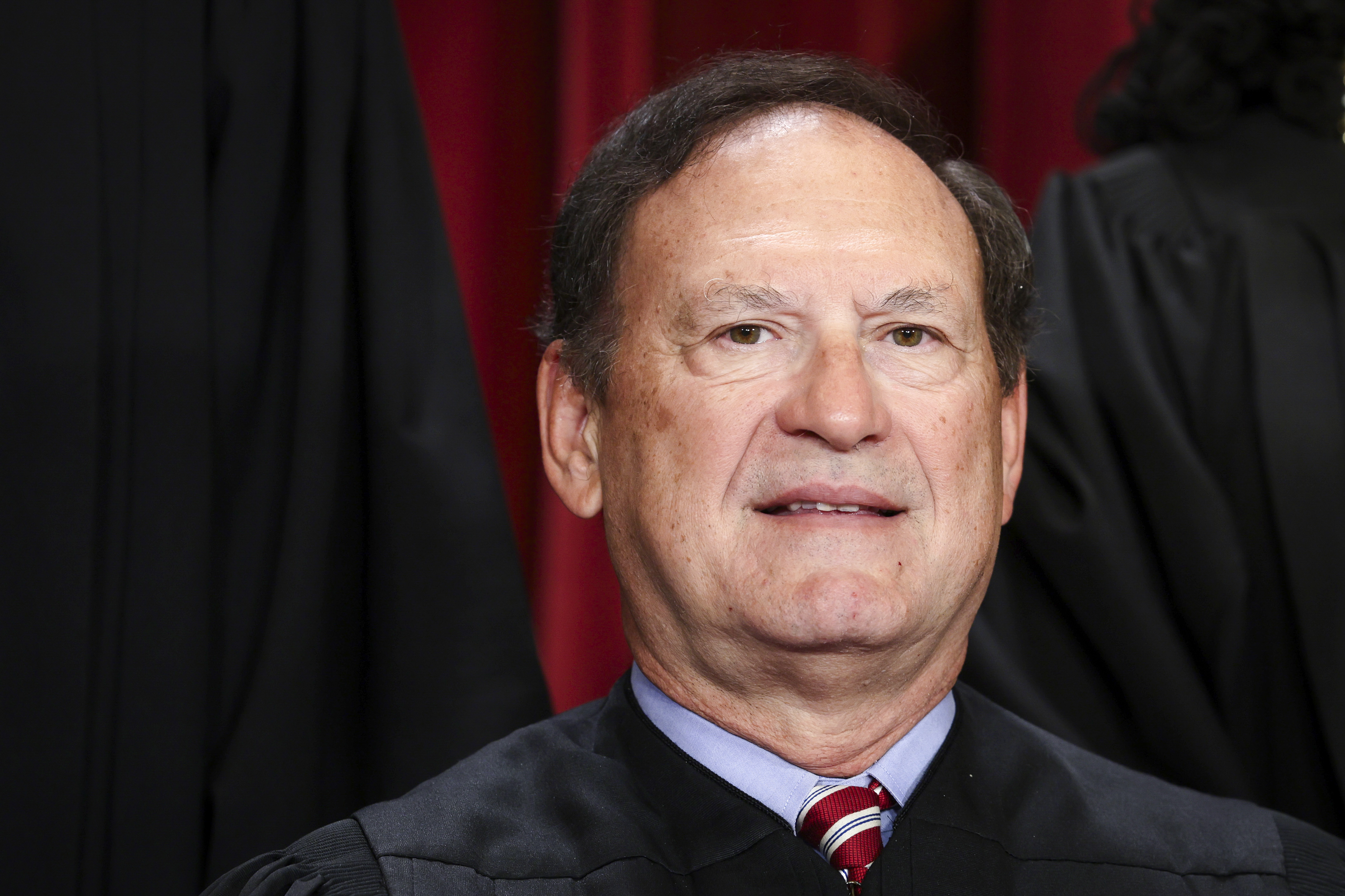

Justice Samuel Alito wrote the majority opinion in City and County of San Francisco v. EPA. The opinion was joined by Chief Justice John Roberts, along with Justices Clarence Thomas, Brett Kavanaugh, and Neil Gorsuch.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett wrote a dissenting opinion that was joined by Justices Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, and Ketanji Brown Jackson.

The nation’s highest court ruled that the EPA must provide specific effluent limitations to wastewater facilities and the governmental bodies that operate them. Effluent is liquid waste or sewage released into a sea or river.

San Francisco argued in the appeal that the EPA imposed overly vague limitations on how much pollution may be present in wastewater discharged by water utilities. The city said the regulations made it difficult to know if its wastewater systems were in compliance.

The EPA grants permits to local governments and water management authorities under the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES), to limit the amount of pollution flowing into bodies of water.

In court documents, San Francisco said that the EPA directs cities not to pollute water bodies “too much” but does not provide a specific limitation, and this opens the door to uncertainty and makes it hard to comply.

Instead of telling the city “how much it needs to control its discharges to comply with the Act,” the EPA’s “generic prohibitions leave the City vulnerable to enforcement based on whether the Pacific Ocean meets state-adopted water quality standards,” according to the city.

San Francisco argued it was unfair to hold it responsible for polluted Pacific Ocean beaches near the city because the pollution may have come from outside sources.

The EPA said that the city’s wastewater system cannot cope with runoff during storms, leading to pollution being released into the ocean.

The city said it was facing potentially billions of dollars in fines for violating its permit.

After San Francisco challenged the permit, the EPA’s Environmental Appeals Board rejected the challenge in December 2020.

In July 2023, a divided U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit rejected San Francisco’s appeal and affirmed the EPA’s power to specify “general narrative prohibitions” on discharges under the Clean Water Act (CWA).

In oral arguments in October 2024, Frederick Liu of the U.S. Department of Justice said San Francisco was “wrong to argue that limitations like the ones challenged here are never okay.”

Under the Clean Water Act, the agency may issue limitations when it is uncertain that the effluent limitations in the permit are adequate to protect water quality, he said.

In the majority opinion, Alito wrote that “‘end-result’ requirements” in permits “make a permittee responsible for the quality of the water in the body of water into which the permittee discharges pollutants.”

“When a permit contains such requirements, a permittee that punctiliously follows every specific requirement in its permit may nevertheless face crushing penalties if the quality of the water in its receiving waters falls below the applicable standards.”

However, the effluent-limiting provisions of the Clean Water Act do not allow the EPA “to include ‘end-result’ provisions in NPDES permits.”

“Determining what steps a permittee must take to ensure that water quality standards are met is the EPA’s responsibility, and Congress has given it the tools needed to make that determination. If the EPA does what the CWA demands, water quality will not suffer,” Alito wrote.

The Supreme Court reversed the ruling of the Ninth Circuit.

Barrett, who dissented in part, wrote in her opinion that San Francisco’s argument that EPA lacks statutory authority to impose conditions on the discharge of pollutants into the ocean is “wrong.”

The Clean Water Act requires the EPA “to impose ‘any more stringent limitation’ that is ‘necessary to meet ... or required to implement any applicable water quality standard.’”

“Conditions that forbid the city to violate water quality standards are plainly ‘limitations’ on the city’s license to discharge,” Barrett wrote.

The new ruling is the EPA’s fourth loss at the Supreme Court since 2022.

In June 2024, the court temporarily blocked the agency’s “good neighbor” rule that cracks down on states whose industries are said to be contributing to smog. The case was Ohio v. EPA.

In May 2023, the court reined in the power of the EPA to regulate wetlands. The case was Sackett v. EPA.

In the June 2022 ruling in West Virginia v. EPA, the court held the Clean Air Act doesn’t give the EPA broad powers to regulate carbon dioxide emissions.