NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman criticized Boeing and leaders in his own agency on Feb. 19 for their role in the near-failed crew flight of the Starliner spacecraft that left two astronauts on the International Space Station for more than 9 months.

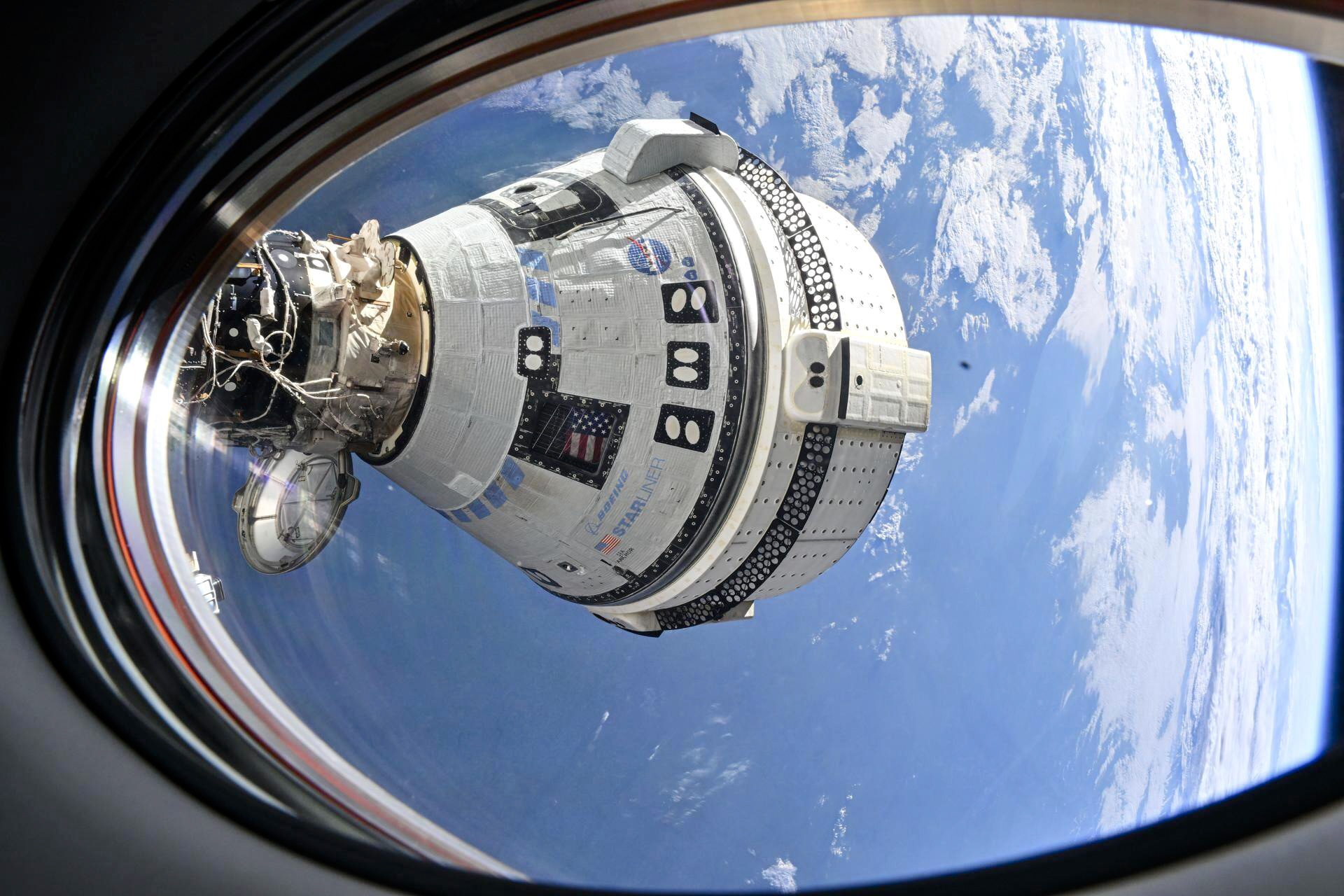

The Boeing CST-100 Starliner is one of several commercial crew and cargo spacecraft in development to further expand access to space. However, it has only flown three times, and only once with a crew on board, due to multiple instrumentation issues, including helium leaks that kept the crewed flight delayed, and thruster failures mid-flight.

Isaacman released the findings of an investigative report, ordered in February 2025 and completed in November 2025, on Starliner during his address. While several functional issues were noted, the administrator and the report called out an institutional and organizational failure on behalf of both NASA and Boeing.

Boeing failed to produce a product that met NASA’s qualifications and crew safety margins, while NASA failed to provide proper oversight of the Starliner development and certification, according to the report. NASA was also not hands-on enough to have proper insight that would have allowed the space agency to understand the problem Boeing was facing, the report stated.

In a letter to NASA employees, Isaacman said that the post-mission investigations after the unmanned flights “did not drive to, or take sufficient action on, the root causes of major anomalies.”

Isaacman also said there was an overwhelming push within NASA to maintain two crew transportation systems that had an influence on the discussions surrounding the operational risks of flying the Starliner.

“Programmatic advocacy exceeded reasonable bounds and placed the mission, the crew, and America’s space program at risk in ways that were not fully understood at the time decisions were being contemplated. This created a culture of mistrust that can never happen again, and there will be leadership accountability,” he said.

Isaacman said he believed the issues were present on every level of the space agency, including up to his predecessor. He did not go into detail about how accountability would be implemented.

Isaacman outlined Starliner’s faulty history and the near-disaster of the crewed mission. He pointed out that thruster failures on the command module—the crew capsule—and the service module were recorded on both unmanned launches of the Starliner, and yet the crewed flight was given the go-ahead.

During that crewed flight, astronauts Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams lost thrusters and had to wait for ground teams to troubleshoot the problem and recover five of the six thrusters to dock. When the capsule returned alone, the thrusters used for reentry were also lost.

“Had different decisions been made, had thrusters not been recovered, or had docking been unsuccessful, the outcome of this mission could have been very, very different,” he said during the press conference.

“NASA will not fly another crew on Starliner until technical causes are understood and corrected, the propulsion system is fully qualified, and appropriate investigation recommendations are implemented,” he added.

Isaacman retroactively declared the situation a “Type A Mishap,” which designates problems that cost more than $2 million, and ensures that it receives the attention of the administrator. It was pointed out by members of the press that the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster in 1986 and the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster in 2003 were also Type A Mishaps credited to missteps made by the leadership and culture at the time.

Isaacman credited the misguided advocacy for Boeing for why the designation was not already in place and said that NASA would succeed through transparency, extreme ownership, decisive action, and competence.

“Transparency is not a weakness, it is a strength,” he said. “We will release the investigation in full, redacted only where legally required, or as directed by our commercial partner. Pretending unpleasant situations did not occur teaches the wrong lessons. Failure to learn invites failure again and suggests that in human spaceflight, failure is an option. It is not.”

Meanwhile, Boeing released its own statement, saying that work on improving Starliner has been ongoing over the past 18 months since the test flight. It was grateful for NASA, stating the report will help strengthen its work in support of mission and crew safety. Boeing emphasized that crew safety is its highest priority.

Now, the clock is ticking for Boeing’s crew capsule to fulfill missions to and from the International Space Station, which is set for decommissioning in 2030. But Isaacman said the spacecraft will be needed by NASA and the growing orbital economy long after the space station.

“At NASA, we see near-endless demand for crew and cargo access to low Earth orbit, well beyond the life of the International Space Station,” he said.

“America is not giving up its presence in low Earth orbit,” he added. “We have an unbelievable, internationally assembled orbiting laboratory right now that’s enabled continuous heartbeat in space for more than a quarter of a century. That will not end with the International Space Station. There will be other space stations, I guarantee it, and they are going to require crew and cargo access to and from low Earth orbit. And I think the nation and the world benefit when you have multiple providers that

are capable of doing that.”