U.S. forces stormed into Venezuela before dawn on Jan. 3 and captured Venezuelan leader Nicolás Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores, in a lightning operation that punched in and out of Caracas before its air defenses could mount an effective response.

The operation resulted in no U.S. fatalities and no loss of U.S. military equipment, U.S. officials said.

The U.S. mission—code-named Operation Absolute Resolve—has quickly become more than a political shockwave. Analysts have said it was also a real-world test of U.S. military power against a country that has spent years buying Chinese- and Russian-made air-defense systems and showcasing them as proof that it could deter Washington.

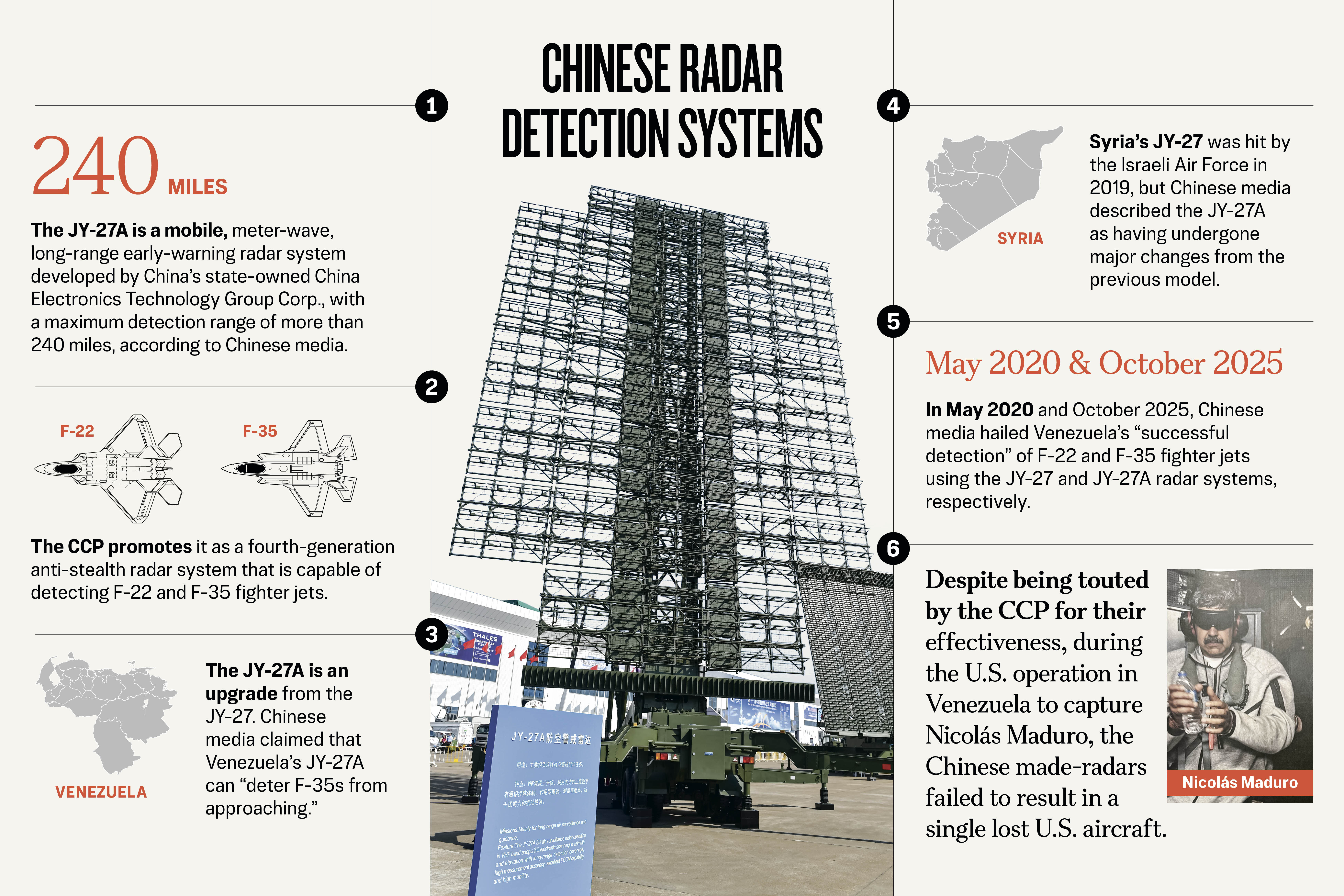

The raid raised uncomfortable questions for Beijing about the limits of the Chinese-supplied systems that Venezuela has leaned on—especially “anti-stealth” radar that China advertised as capable of spotting and stopping U.S. stealth aircraft, a military analyst said.

The analyst told The Epoch Times that the most damaging takeaway for China isn’t the failure of a single piece of equipment—it’s what the operation suggested about deeper weaknesses: corruption in China’s defense industry and lack of reliability of the technology and command structure meant to tie those systems together.

“A system built to look modern on paper and intimidating in propaganda falls apart under the demands of real combat,” said Yu Tsung-chi, a retired major general from Taiwan and former president of the Political Warfare College at Taiwan’s National Defense University.

He said Beijing’s performance claims often lean more on messaging than combat validation.

China condemned the capture of Maduro and accused Washington of acting as a “world judge,” in a blunt response that underscored how closely Beijing saw the fallout tied to its influence and credibility in Latin America.

Operation Measured in Hours

President Donald Trump ordered the operation at 10:46 p.m. ET on Jan. 2, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Dan Caine said.

Aircraft launched from about 20 land and sea bases across the Western Hemisphere, and the helicopter force approached Venezuela at roughly 100 feet above the water to maintain the element of surprise.

Within five hours, by 3:29 a.m. ET, U.S. forces had Maduro and Flores aboard the USS Iwo Jima, an amphibious assault ship. They were then flown to the United States.

This illustration depicts Caracas and the states in which the Venezuelan regime said U.S. military strikes occurred before the capture of Venezuelan leader Nicolás Maduro and his wife on Jan. 3, 2025. (Anika Arora Seth, Phil Holm via AP)

(Left) The Fuerte Tiuna neighborhood of Caracas, Venezuela, on Dec. 22, 2025. (Right) The same neighborhood after U.S. strikes on Jan. 3, 2026. U.S. forces carried out a pre-dawn raid in Caracas, capturing Venezuelan leader Nicolás Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores, and flying them to the United States to face federal charges. (©2026 Vantor via AP)

U.S. officials said the operation involved more than 150 aircraft along with integrated electronic attack and nonkinetic effects from U.S. Cyber Command, Space Command, and other assets to suppress Venezuelan defenses and clear a path for the helicopters.

Briefings described a layered effects approach: bombers, fighters, surveillance and reconnaissance aircraft, electronic warfare jets, and drones overhead; space and cyber support to disrupt Venezuelan systems; and strikes intended to dismantle and disable air defenses as helicopters closed on Caracas.

According to officials, aircraft used in the operation included B-1B bombers, F-22 Raptors, F-35 Lightning II fighters, EA-18G Growler electronic attack jets, E-2 Hawkeye early warning aircraft, and numerous drones alongside transport and helicopter assets.

(Top Left) A B-1B Lancer flies over the Pacific Ocean during a Bomber Task Force mission on June 20, 2022. (Top Right) Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) F-35A Lightning IIs receive fuel from a RAAF KC-30A Multi-Role Tanker Transport over Australia during Talisman Sabre 23 on July 23, 2023. (Bottom Left) An RAAF EA-18G Growler takes off from Amberley, Australia, for a mission during Red Flag 23-1 at Nellis Air Force Base, Nev., on Jan. 24, 2023. (Bottom Right) An E-2C Hawkeye assigned to the Greyhawks of Carrier Airborne Early Warning Squadron (VAW) 120 flies over Jacksonville, Fla., in this file image. (Master Sgt. Nicholas Priest/U.S. Air Force; Tech. Sgt. Eric Summers Jr./CC-PD-Mark; William R. Lewis/U.S. Air Force/Public Domain; Lt. j.g. John A. Ivancic/U.S. Navy)

China’s Systems

For years, Venezuela has spent heavily on Chinese and Russian equipment while claiming that it was building one of the region’s most modern defense systems.

In recent months, reports have highlighted Venezuela’s installation of Chinese-made JY-27A radar units, marketed as able to detect “low-observable” aircraft—exactly the kind of system meant to complicate U.S. operations involving stealth platforms.

That promise did not hold on Jan. 3.

Yu said neither Chinese nor Russian air-defense systems “made the slightest bit of difference” once the United States brought real-time intelligence, electronic warfare, and precision weapons to bear.

The real contest, he said, wasn’t just radar range or missile specs, but a fast chain of detection, communications, decision-making, and joint execution—exactly where weaker militaries tend to break.

Beyond radar, Venezuela has also displayed and fielded Chinese-made ground systems that Beijing has marketed abroad—from VN-16 amphibious assault vehicles and VN-18 infantry fighting vehicles to Chinese rocket artillery systems.

Venezuelan parades in recent years have showcased those platforms as symbols of a growing partnership and a tougher military posture.

But Yu said glossy displays don’t matter much if the wider network—sensors, communications, command, training, and logistics—can’t hold up under pressure.

A view of telecommunications antennas in El Volcan in Caracas, Venezuela, on Jan. 5, 2026. El Volcan was one of the first points of attack during the Jan. 3 capture of Venezuelan leader Nicolás Maduro by U.S. forces. (Carlos Becerra/Getty Images)

Parades Versus Combat Reality

Yu said the U.S. raid on Caracas exposed the limits of China’s propaganda-first military culture—one that rewards polished demonstrations more than hard, repeated combat validation.

He said the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has not fought a major war since 1979, and it studies foreign conflicts in part because it lacks large-scale, recent battlefield feedback of its own.

“You can look perfectly aligned and advanced on a parade ground,” Yu said, “but without real combat to back it up, it’s all just stage effects.”

The U.S. operation in Venezuela, he said, hit Beijing especially hard because the communist regime has spent years promoting its weapons and integrated combat systems as “world-leading,” using high-profile showcases—such as the much-hyped military parade in September 2025—to project confidence at home and deterrence abroad.

In that vein, Yu said, “anti-stealth” detection is a headline capability meant to signal that China can threaten U.S. airpower. But what happened in Caracas cut straight through that messaging.

Yu also pointed to reports that a Chinese delegation visited Venezuela just hours before Maduro’s capture, further spotlighting how closely Beijing and Caracas have aligned.

Radars are displayed during a military parade marking the 80th anniversary of victory over Japan and the end of World War II, at Tiananmen Square in Beijing on Sept. 3, 2025. For years, Venezuela has spent heavily on Chinese and Russian equipment while claiming that it was building one of the region’s most modern defense systems. (Pedro Pardo/AFP via Getty Images)

Corruption, Command Liabilities

Yu said corruption and “black-box” decision-making have weakened Chinese military readiness, partly because bad news gets filtered upward and procurement incentives reward appearances.

He pointed to recent corruption probes in China’s military-industrial complex and scandals that have raised questions about quality control and readiness.

In a closed system, he said, procurement decisions often happen behind doors, with limited independent oversight and strong incentives to hide failure.

Beijing’s “military-civil fusion” model can intensify those risks, Yu said. Profit-driven contractors pay bribes to obtain contracts, substitute inferior components, and still meet paperwork requirements as long as money moves and reporting looks clean.

Even if individual platforms are capable, he said, the system around them—maintenance, training realism, logistics honesty—can be hollowed out.

He contrasted that with what he described as Washington’s preference for letting battlefield results speak louder than slogans.

Yu also said integration and command speed often decide outcomes faster than platform specs.

The U.S. advantage, he said, is not just technology—it’s integration and delegation. Once a mission is approved, U.S. operations are designed to push authority downward, giving frontline commanders room to adjust in seconds.

President Donald Trump (2nd R) looks on as Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Dan Caine (2nd L) speaks to the press following U.S. military actions in Venezuela, at Mar-a-Lago in Palm Beach, Fla., on Jan. 3, 2026. (Jim Watson/AFP via Getty Images)

China’s command system, he said, is the opposite: rigidly centralized and politically constrained.

“No matter how advanced the equipment,” Yu said, “it still has to wait for orders from the highest authority.”

Centralization is a built-in lag, he said, which is costly in a fight in which delays are punished instantly.

Yu said he believes that Washington’s decision to capture Maduro was meant to send a message well beyond Caracas: to Beijing, to pro-China and anti-U.S. governments, such as Cuba and Iran, and to other Latin American capitals weighing closer ties with China.

He framed the move as a hard-edged application of the Monroe Doctrine under Trump’s second-term national security approach—prioritizing U.S. security in the Western Hemisphere and working to block Beijing-aligned influence from taking root further in Central and South America.

“Venezuela may only be the first domino,” Yu said. “Pro-Beijing regimes across Latin America will face growing pressure to choose sides.”

Cheng Mulan and Luo Ya contributed to this report.