Labels for popular weight-loss drugs no longer need to warn that they may increase the risk of suicide, federal regulators said in a Jan. 13 update.

The Food and Drug Administration said that it informed companies that manufacture Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists that labels for the drugs no longer need to mention suicidal behavior and ideation.

The labels currently say that people who received GLP-1 drugs in clinical trials have experienced suicidal thoughts and that doctors should monitor patients “for the emergence or worsening of depression, suicidal thoughts or behavior, and/or any unusual changes in mood or behavior” after they start one of the medications.

The labels also advise discontinuing usage of the drugs in patients who experience suicidal thoughts or behavior, and that people with a history of suicidal attempts should not receive them.

The labels have featured the warnings since the FDA approved the products, which mimic a natural hormone and give people the feeling of being full, in recent years. Some regulators have removed warnings about suicide, but others, such as in Australia, have maintained them.

The FDA in 2024 said a preliminary review did not find evidence that the medicines cause suicidal thoughts or actions. Regulators said this week that a comprehensive review found no increased risk associated with the GLP-1 products.

The review analyzed data from health care claims for 2.2 million people, of whom about half received a GLP-1 drug. The other half received an SSGLT2 inhibitor, a class of drugs given to people with conditions such as diabetes.

GLP-1 users did not have a higher rate of intentional self-harm when compared to the other group.

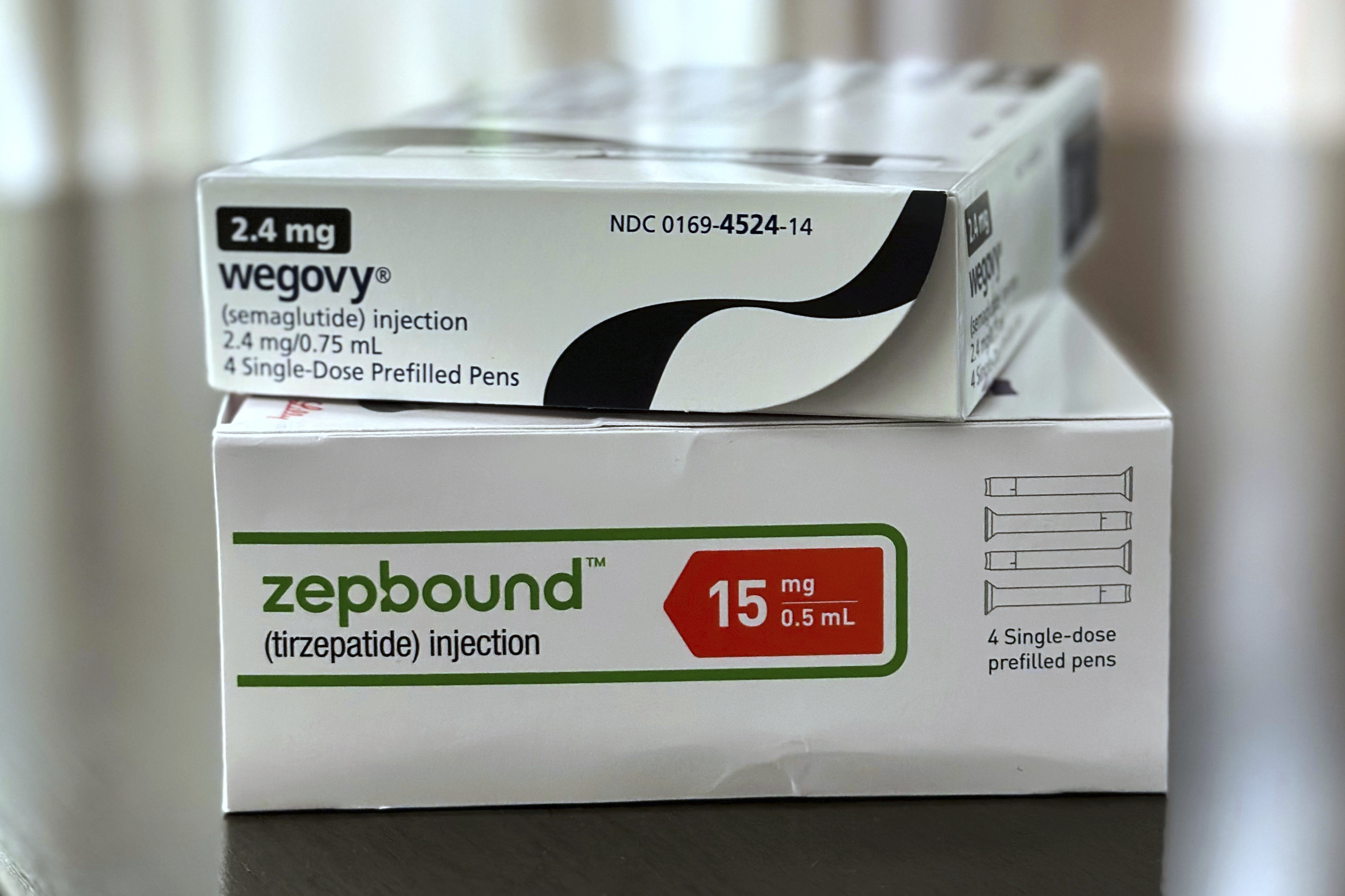

The move impacts three products: Saxenda and Wegovy, both made by Novo Nordisk, and Zepbound, made by Eli Lilly.

“We are happy to see the FDA’s recommendation,” a spokesperson for Novo Nordisk told The Epoch Times in an email.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in White Oak, Md., on June 5, 2023. (Madalina Vasiliu/The Epoch Times)

The company noted that additional known risks of the products will remain on the labels and said it would keep working with regulatory authorities to monitor the safety of the medicines.

“We appreciate the FDA’s careful consideration of this important safety issue. Patient safety is Lilly’s top priority, and we will continue to work with the FDA on next steps to ensure that appropriate safety information is available to prescribers,” a Lilly spokesperson told The Epoch Times via email.

The spokesperson said people who experience side effects should speak with their health care provider.

“This is a reasonable decision based on careful review of the clinical phase 3 trial data for Wegovy and Zepbound and independent review by the FDA,” Dr. Robert Kushner, professor emeritus at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, told The Epoch Times in an email. “However, patients being treated by these medications should still be periodically assessed for changes in mood or symptoms of depression.”

Several others disagreed with removing the warning.

“Removal of the warning about a potential risk of suicidal thoughts from GLP-1 weight loss drugs is premature as research studies have shown mixed results regarding the association between GLP-1 agonists and suicidal behavior,” Dr. Vanita Rahman, clinic director for the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine, told The Epoch Times via email.

A 2024 paper found indications that GLP-1 medications led to suicidal ideation, although a study earlier that year found no link between the two.

Rahman also said that the weight-loss drugs have other risks and limitations, pointing to research that found that users often regain lost weight after they stop using the drugs.

Kim Witczak, founder of the drug safety group Woodymatters, said the FDA’s move was unusual because uncertainty remains, and it can be difficult to detect rare psychiatric harms.

“We have seen this pattern before with antidepressants, where early concerns about suicidality were minimized and only later acknowledged through post-marketing data and lived experience,” Witczak told The Epoch Times in an email.

Witczak said the warnings were never meant to scare patients, but to ensure awareness and early intervention if symptoms emerged.

“It is also important to note that most clinical trials exclude people with active depression or prior suicidal behavior, which limits how confidently findings can be generalized to real-world use. In addition, removing a warning can unintentionally reduce monitoring and reporting, as doctors and patients won’t look for or report symptoms once a risk is no longer highlighted. It can send the signal that the concern has been resolved and the product is safe,” she said.