Chronic pain isn’t just a matter of aching muscles or lingering injuries—it can also be a silent echo of unprocessed emotions.

Surprisingly, the roots of persistent pain often stretch back to early life experiences, with a strong connection between adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and chronic pain. Studies find that these experiences are linked to heightened pain catastrophizing (expecting the worst from pain) and pain complications (additional problems from chronic pain) later in life, as well as depression.

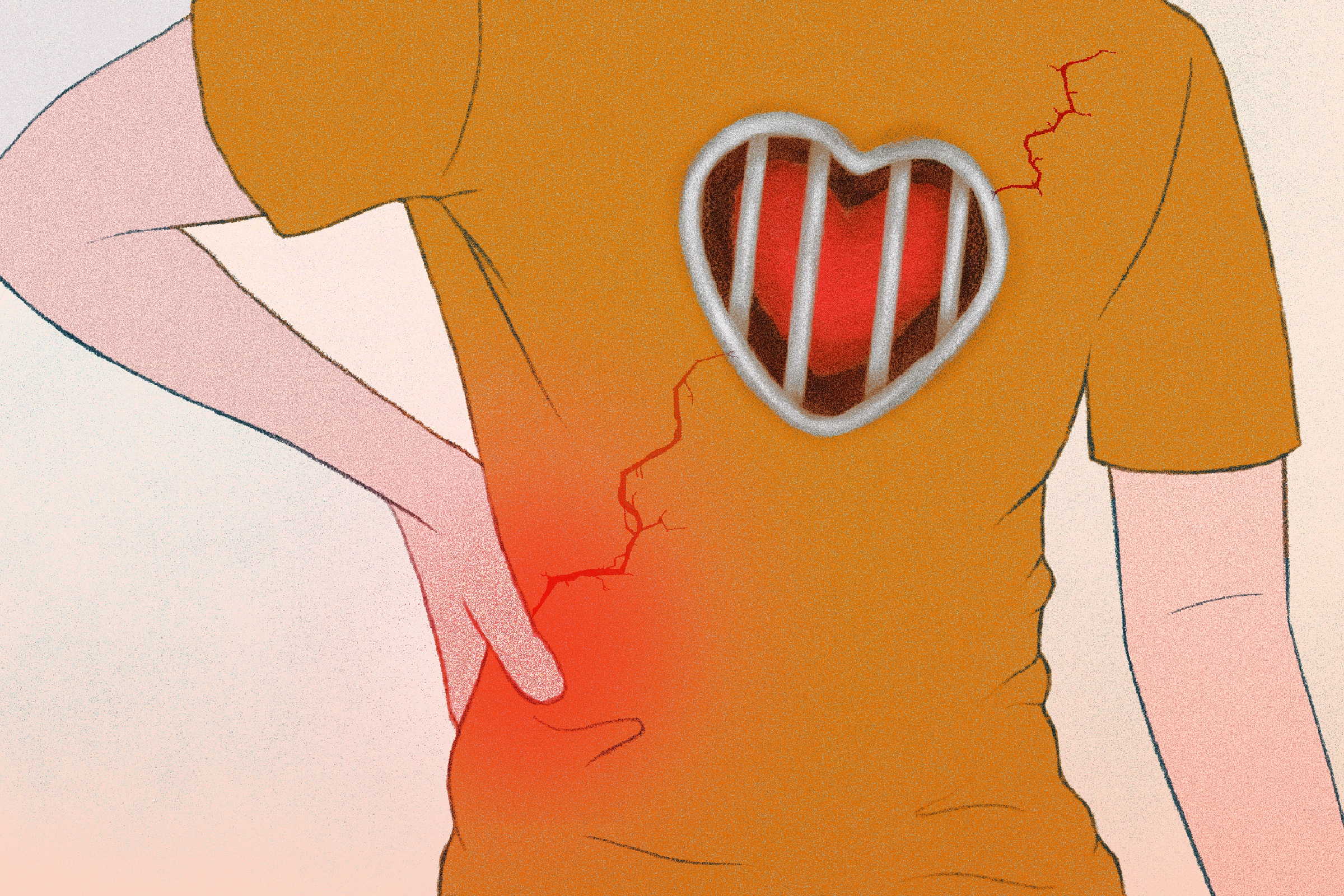

Trapped Emotions

“Emotion is energy in motion,” Lidalize Grobler, an educational psychologist, told The Epoch Times. When we experience positive emotions, we naturally allow them to flow and enjoy the feeling. However, as a society, we often feel the need to suppress negative emotions.

When the “energy in motion” becomes trapped within the body, it can accumulate without a chance to be released. This buildup may manifest as chronic pain, serving as the body’s way of signaling that something unresolved needs attention.

Over time, this trapped energy can become deeply embedded in our system, straining the body’s capacity to contain it.

This is what happens with ACEs.

Research indicates that 84 percent of adults with chronic pain report experiencing at least one ACE, compared with nearly 62 percent of the general population. Additionally, the incidence of chronic pain appears to double among people with ACEs, and these individuals often experience increased pain severity.

“Ninety-three percent of patients referred to us for fibromyalgia pain had significant, unaddressed ACEs,” Elaine Wilkins, a coach, National Health Service trainer, and founder of The Chrysalis Effect, an online program for recovering from myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia, told The Epoch Times. Fibromyalgia is a common chronic condition that causes muscle pain throughout the body.

Specifically, childhood neglect and abuse—whether physical or sexual—are associated with conditions such as fibromyalgia in adulthood, with physical abuse more strongly related. Furthermore, a history of physical abuse during childhood has been linked to a higher risk of neck and back pain in adulthood.

This seems to be because childhood adversity can significantly alter stress reactivity and lead to immunological dysregulation, which is associated with increased inflammation and may result in widespread pain. Studies have shown that severe inflammation can persist in individuals with multiple ACEs, even up to 30 years later.

These early experiences, while often preverbal, are stored in the brain as feeling memories, triggering emotions that become trapped in the body, according to Wilkins.

The period before age 6 is particularly critical for neuroendocrine development, making childhood a sensitive time for emotional and physiological growth. Prolonged exposure to stressors during this developmental window can be especially traumatizing.

According to a study in The Lancet Regional Health Americas, ACEs have an effect on adult survival and health. More specifically, children with two or more ACEs had a higher risk of dying young.

Not Any Less Real

The development and persistence of chronic pain are understood to result from a complex interplay of social, psychological, and biological factors. According to the 2020

article, pain is an unpleasant subjective experience with both emotional and sensory components.

The U.S. Pain Foundation emphasizes that even if the physical aspects of an injury or condition have healed, unresolved stress and emotions can prevent us from becoming pain-free. Key emotions that can result in pain include helplessness, grief, anger, guilt, anxiety, and fear.

This does not mean that if you’re experiencing pain because of emotional factors, the pain is any less real, according to Wilkins.

“We now understand that the brain processes physical and emotional pain using the same pathways, so what you feel is real,” she said.

As a society, we often fail to recognize the physical impact of emotions on the body. Grobler said that just as a hip injury can cause pain in the knee, we don’t dismiss the knee pain as it’s “all in your head.” Yet when it comes to emotional pain, people often resort to these dismissive attitudes.

A ‘Smoke Alarm’

“Pain is the body’s way of asking you to pay attention, signaling that something is not right. It’s like a smoke alarm,” Wilkins said. It prompts people to change.

However, instead of listening to this wisdom, many people continue engaging in behaviors that perpetuate their pain, resorting to self-medication with pills, alcohol, overworking, overspending, or people-pleasing to maintain approval. This tendency is powerful when unresolved trauma makes us prioritize attachment (staying connected to our caregivers) over authenticity (developing a sense of self).

Because pain is a message, if we rush to eliminate it, we miss the opportunity to understand its underlying cause and may even harm ourselves further, much like how taking pain medication to push through an injury can exacerbate it, Grobler said.

“Perhaps we need to reflect and sit with the pain, asking ourselves: What am I not hearing?” she said. “It’s like a baby crying without being able to speak. Is it hungry, cold, or does it have a stomachache? Sometimes, it’s a matter of trial and error. Pain doesn’t come with a language.”

Addressing Pain

When experiencing chronic pain that you suspect might be caused by emotions or adverse childhood experiences, Grobler emphasized the importance of seeking therapy, as it provides an opportunity to analyze, comprehend, and express feelings that you may have suppressed for a long time.

“Often, we are not fully cognitively aware of the emotions that are causing pain, especially if the events occurred long ago, perhaps even during preverbal stages. This can leave those experiences trapped in our bodies. Therefore, a body-based approach, or treatments that use physical movement and body awareness as therapy, is essential, as these issues cannot be resolved solely on a cognitive level,” she said.

While cognitive behavioral therapy and psychoanalysis can help you understand what has happened, they may not fully address unprocessed emotions residing in the body. You may find it difficult to make lasting changes without incorporating body-based therapy.

Approaches such as eye movement desensitization and reprocessing; brain working recursive therapy; tension and trauma release exercises; or somatic experiencing can provide a deeper understanding of yourself and facilitate healing, Grobler said.

Wilkins recommended journaling when experiencing a flare-up to reflect on any events, conflicts, stressors, and emotions that may have contributed to the situation. She suggests asking yourself the following questions:

- What has affected me so profoundly that my body is urging me to listen?

- If I am being 100 percent honest, what do I truly want to do?

- What am I dreading, or whom do I want to avoid seeing?

- What is my pain helping me avoid?

- Am I moving my body enough?

- What activities have I given up that I once loved?

Grobler used a gas chamber as a metaphor: The buildup of emotion is like gas accumulation. The key lies in finding the underlying stressors and ways to “open the door” and permit this pent-up energy to release, she said.