American comic-book character Superman debuted in 1938, then gained the moniker “Man of Steel” to burnish his credentials of unflinching courage, unpliable character, unwavering moral certitude, unbending fairness, and near-indestructible strength. It stuck. Forty years later, 26-year-old actor Christopher Reeve, began a 26-year journey that would last until his death in 2004, establishing him both as a Kansas-raised superman on screen and an all-American man of steel off it.

Born in 1952 in New York, Reeve studied at Cornell and Juilliard School of Performing Arts. After graduation, he worked in the theater for a couple years before his 1978 film debut as a minor character in the Charlton Heston starrer “Gray Lady Down.” The following year, producers of the new film “Superman” offered Reeve the role that would make him a global sensation.

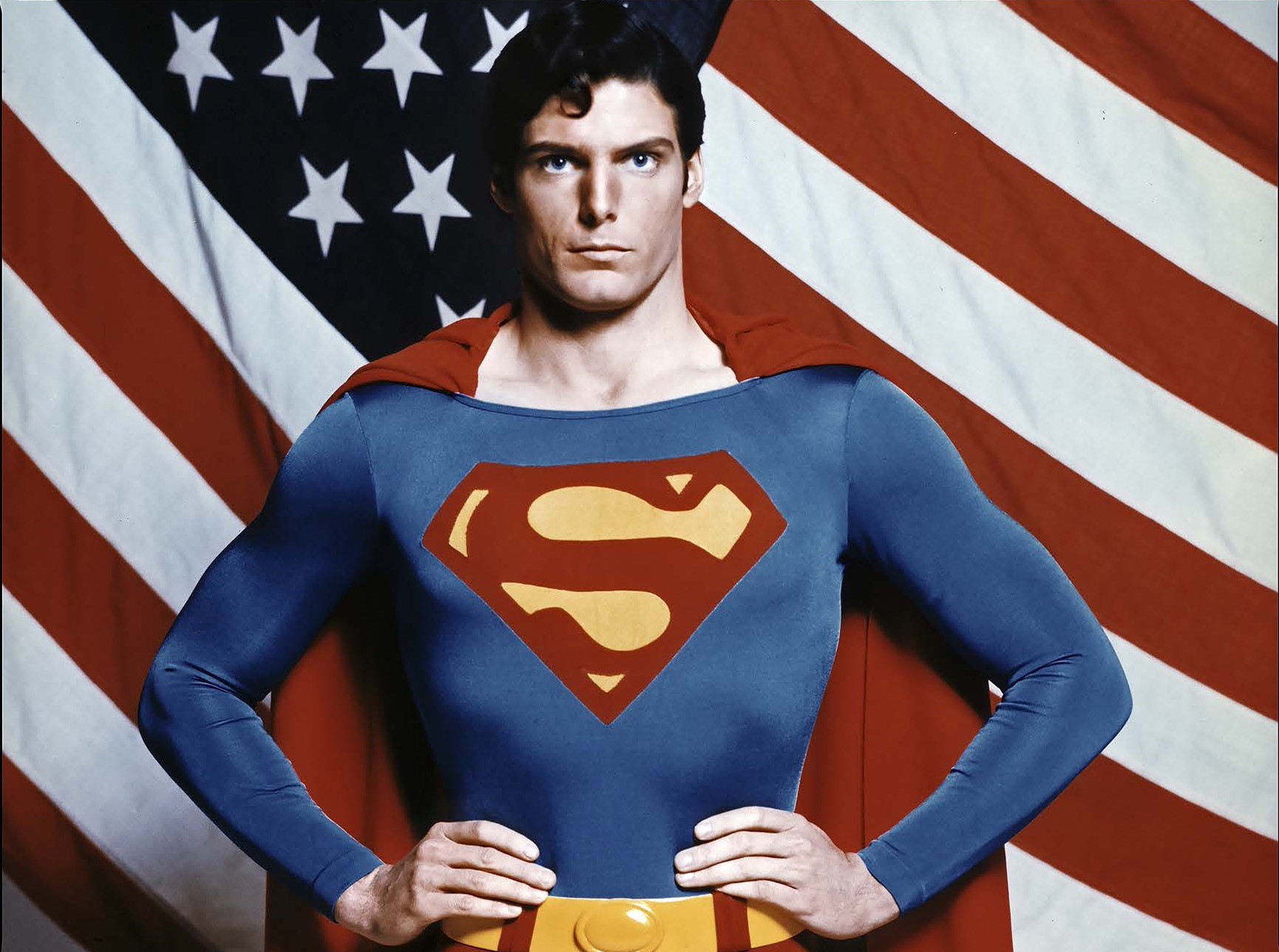

The 6-foot-4-inch Reeve towered, even among tall men; he remains the tallest of Superman actors. In interviews, Crystal Field, co-founder of Theater for the New City, remembers the 23-year-old in a bit part, “I don’t remember the monologue. I remember him. … He was very handsome.” Actor-friend Robin Williams once joked about how the bull-necked Reeve had to swivel at doorways just so his broad shoulders wouldn’t catch the sides. Producer Ilya Salkind recalled, “He had this big neck. … Superman has a big neck.”

No actor, before him or since, has looked the part as Reeve did, in as many as four films, over nearly a decade. Yet, for all his looks, Reeve didn’t preen over his physique. To him, it was only a starting point. In that first film, Superman grants his first interview to reporter Lois Lane. Stunned by his blue-eyed, godlike aura, she stammers her question. Why is he here on his adopted planet earth? Reeve’s Superman steps forward, “I’m here to fight for truth and justice and the American way.”

After an intense two-month training regimen, Reeve added 30 pounds of muscle to his 6'4" frame. (MovieStillsDB)

Reeve’s unapologetically virtuous portrayal shaped the superhero film genre that followed, but he crafted his hero around family values, patriotism, and steadfastness; one who was loved and respected by the upright, not just feared by the unscrupulous. As the superlative immigrant, he was no entitled alien superbrat. He submitted to earth’s laws, played by earth’s rules. Comic book artist Jim Lee clarified, “It was all about, can you adapt and fit into a society.” Reeve’s Superman answered that poser in spades, with respect, restraint, and humility.

Growing up amid his parents’ divorce, and circumspect about commitment, Reeve struggled with relationships for years, before marrying and staying a devoted husband to actress-singer Dana Morosini. He did play other characters but to millions of moviegoers, not one as memorable as his first starring role: the Man of Steel who could walk tall, run fast, and fly even faster.

Superhuman Courage and Compassion

Reeve reads the winner of the Emmy for "Outstanding Supporting Actor for a Mini-series or Special" at the 1997 Emmy Awards. (Tiziana Sorge/ Getty Images)

In 1995, disaster struck. A horse-riding accident crippled Reeve. Suddenly a quadriplegic, he was told he’d never move again, let alone stand, walk, or run. So debilitating were his spinal injuries that he’d contemplated suicide to spare himself and others prolonged agony. What kept him going? As he wrestled with enforced incapacity, Dana reassured him, “You’re still you. And I love you.” Unsurprisingly, he named his autobiography, “Still Me.” He wrote of how her words were an affirmation that “marriage and family stood at the center … if both were intact, so was your universe.”

In another book “Nothing Is Impossible: Reflections on a New Life,” Reeve explained how love nurtures self-acceptance, and how both can spur humans to aspire to the superhuman. Not that Reeve didn’t show steely resolve before; in 1987 he flew to Chile to protest dictator Pinochet’s threat to execute several actors, and he ended up saving lives. But it’s after his paralysis that his steel really shone.

Cover of Reeve's 2004 book "Nothing is Impossible: Reflections on a New Life."

Chillingly, weeks before the accident, Reeve studied what it’d be like to be a wheelchair-bound paraplegic, then starred as one in the film “Above Suspicion.” Later, wheelchair-bound for real, he sprung to action, vowing to get better and to help those battling paralysis. He defied medical predictions and regained control over some bodily functions, saying, “Even if your body doesn’t work the way it used to, the heart and the mind and the spirit are not diminished.” He went on to act again, even direct. But it’s as a champion of disability rights that he came into his own.

Reeve helped pass the Work Incentives Improvement Act that enables continued benefits to disabled people returning to work. The Christopher & Dana Reeve Foundation that he and his wife began in 2002 has since raised $130 million for research, given $30 million in grants and helped over 100,000 survivors and their families. Dana succumbed to cancer two years after Reeve died of heart failure, but not before she spent years focusing on “today’s care” while he dwelt on finding “tomorrow’s cure.”

Their lobbying led to a first-of-its-kind Christopher and Dana Reeve Paralysis Act mandating American government investment of $25 million a year from 2010 to 2013 in paralysis-related research, rehabilitation and advocacy. Reeve’s foregrounding of disability rights by playing host at Atlanta’s 1996 Paralympics helped place the until-then peripheral Paralympics on par with mainstream games.

Echoing Superman’s selfless code, Reeve wrote of how gratitude for the gift of life helped him move past self-pity, “You try to behave in … the most loving way you can manage. … Thinking that way helped me get past … my body, my problems, my condition.” In interviews, son William recalls Reeve’s benign physical presence as a father, but adds that, to children, it’s the emotional, mental, even spiritual presence of parents that matters.

"Super/Man: The Christopher Reeve Story" will be in theatres only on Sept. 21 and Sept. 25. (Warner Bros. Pictures)

The documentary “Super/Man: The Christopher Reeve Story” (2024), marks Reeve’s 20th death anniversary. It features interviews with his children Matthew and Alexandra, from a previous relationship with Gae Exton, and with his son William, from his marriage to Dana. It invites audiences to challenge notions that impose a blindness to what disabled people can do and a deafness to what science can do for them; to reimagine a world where the disabled can lead happy, fulfilling lives.

Like the superhero he immortalized, Reeve cultivated super-sight and super-hearing, to see and hear what others couldn’t. Except, he was looking and listening for how he could rescue or reassure paralysis survivors with the strong arms of his fame, his credibility. Fond of saying, “Once you choose hope, anything’s possible,” Reeve admitted being impatient with able-bodied people who’re somehow paralyzed in not leveraging life’s opportunities.

Reeve was an accomplished hang-glider, pilot, pianist, scuba-diver, sailor, skier and canoeist. For a man who played the epitome of physicality on screen to be denied nearly all of that off-screen, Reeve valiantly upheld the emotional, moral aspects of life, unlike celebrities who promote the merely cosmetic.

Reeve addresses an audience at the National Press Club in Washington, 1999. After Reeves was paralyzed from a horse fall in 1995, he became a quadriplegic and disabilities rights activist. (Joyce Naltchayan /Getty Images)

It’s tempting to see Reeve’s life as a tragic mirroring of the Superman myth, as if his accident rendered him feeble, like his needy cinematic alter ego Clark Kent. But it’s more useful to see it as the reverse. After all, special effects technicians used pre- and post-production finessing to make Reeve seem invincible on film. In reality? Once paralyzed, every move he made was his own: lifting a finger, controlling his voice, maneuvering his wheelchair or ventilator. Through repeated, stupefyingly heroic acts of sheer will, Reeve had made his Kent, Superman.

Onscreen, kryptonite, the rock-like material from his home planet, is about the only thing that can weaken, even kill Superman. Off-screen, Christopher Reeve proved to the world that kryptonite is an otherwise lifeless metaphor for fear and self-loathing. Sure, if we let it, it can come alive, throbbing green as it were, crippling us. But if we unleash the courage and compassion within us, as Reeve did, we can unfasten its grip. Then, we might stand, when others expect us to merely sit. We might run, when asked to walk. Who knows? We might even fly.

Made without computer special effects, "Superman" was the first film to realistically show a person flying. Reeve's former glider pilot training helped his flying aerodynamics for his role as Superman. (MovieStillsDB)

What arts and culture topics would you like us to cover? Please email ideas or feedback to features@epochtimes.nyc