Dale Anderson was in 7th grade when a wildlife educator brought a mountain lion to his classroom, marking the moment he began dreaming about working with big cats—a passion he described as a “God-given desire to help his creation.”

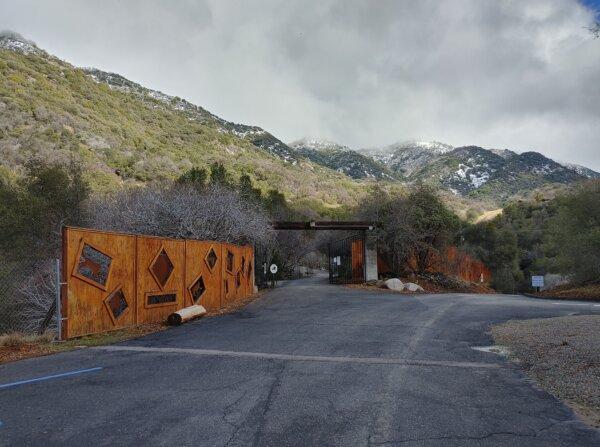

His love for big cats is on full display at Project Survival Cat Haven, an interactive park spanning 93 acres in Dunlap, California, about 40 miles east of Fresno.

Nestled just off Highway 180 outside the Kings Canyon National Park entrance, Mr. Anderson describes his facility as a “scenic byway zoo” specializing in educating visitors about big cats and conservation efforts to preserve endangered species.

Breeds such as jaguars, lions, and bobcats have always fascinated Mr. Anderson, and his passion for learning about these creatures began while he was working as an airline pilot in California.

Raised in Santa Rosa—about one hour north of San Francisco—he attended college at Oregon State and studied engineering. After deciding the discipline wasn’t for him, he pivoted to flying airplanes for AirWest and ended up in the Fresno area.

Amid a busy airline schedule, he also began working at the Exotic Feline Breeding Compound in Southern California, driving three and a half hours, four days a week, to receive wildlife training and earn his restricted species permit, required in California for anyone who wants to own an exotic animal like a mountain lion.

His love for big cats culminated in 1992 when he purchased property in the California foothills that would soon become Project Survival Cat Haven.

“When I started there was nothing there, it was a blank piece of property,” he told The Epoch Times.

A lion at the Cat Haven. (Courtesy of Dale Anderson)

It took six years to complete construction and development on the property before Cat Haven opened to the public in 1998. Mr. Anderson quit his airline job and began working full-time on the property, where he built habitats for big cats and designed a walking trail for visitors to view them.

It took nearly 10 years for the park to reach a comfortable financial operating status, he said, and after two and a half decades, taking care of the animals in the park is still an ongoing challenge, especially in a high fire-hazard area like the California foothills.

In June, the park was threatened by the Flash fire, which burned several thousand acres roughly 15 minutes east of the haven. They didn’t have to evacuate, but they lost power and cell service.

“You have to be prepared to deal with it,” he said.

Mr. Anderson, 64, said his facility is prepared to transport the big cats if they are ordered, in the future, to evacuate. Many of them, he said, are crate-trained to assist with easy transportation. He has also met with emergency departments like Cal Fire and the Fresno County Sherriff’s office to establish contingency plans for what “needs to happen” if needed.

Despite logistical challenges, Cat Haven has become an educational opportunity embraced by local schools looking for resources about feline conservation.

Mr. Anderson said the destination is a “focal point” that provides a platform to educate visitors about big cats and point them toward supporting conservation efforts.

About half of the big cats, like tigers and amur leopards, are endangered. Mr. Anderson said he is not a rescue or rehabilitation facility, and when he receives animals from zoological facilities across the country, they are generally in very good health and have either been part of a breeding program or raised in captivity after being orphaned in the wild.

“Conservation is [work] out in the field trying to preserve these cats in the wild,” he said. “Having the cats on display is education.”

The entrance to Cat Haven, which offers guided tours, a summer camp, and onsite classes. (Courtesy of Dale Anderson)

The haven’s goal is to motivate visitors to fund and support conservation efforts to save endangered species like tigers.

The facility is open weekly and requires a team of around 30 people to operate. They offer guided tours, “Cat Camp,” for kids during the summer, and a variety of onsite classes for students on field trips.

They also bring “ambassador cats” to school classrooms allowing kids to interact with the animals, and to learn about conservation efforts and how to support them.

Saving big cats in the wild, Mr. Anderson said, is centered largely on conflict management.

“The majority of the cats and the majority of the people in the middle are going to work together,” he said, calling for a middle ground between extreme animal activists and those who are opposed to activism in general, like poachers.

“Over the past 30 years, have we made progress saving cats? Probably not ... we need to figure out how to have cats and people live together,” he said.

Mr. Anderson’s favorite is the jaguar, which he said used to be native to California.

“The last one was killed around 1860 or so,” he said.

Visitors to the haven can see 38 big cats, including jaguars, along with lynxes, bobcats, leopards, cheetahs, caracals, lions, cougars, and snow leopards.

As a nonprofit, the site operates completely on donations and relies heavily on volunteer work, with jobs ranging from hosting guided tours to helping with habitat construction.

“I have this passion that it’s a good thing to try to help cats,” he said.

Cat Haven is open six days a week during the summer. In the winter, it is closed Tuesdays and Wednesdays. General admission for adults is $17 and $12 for children.