Maurine Molak has spent the past eight years advocating for online safety for children.

A year after her son David died by suicide due to cyberbullying in 2016, she pushed for a new law, also known as “David’s Law,” in her home state of Texas.

It makes cyberbullying a criminal offense and allows victims to seek injunctive relief against social media accounts used to harass or bully minors.

When David’s Law was passed in 2017 in Texas, certain provisions requiring social media companies to prevent anonymous cyberbullying were removed from the bill.

Ms. Molak said she believes this was because of those companies’ lobbying, and she vowed to address the issue on the federal level.

Her latest focus is the Kids Online Safety Act (KOSA), a bill that requires social media companies to take measures to prevent the spread of harmful content, including that related to suicide, eating disorders, bullying, and drugs.

The bill would also require tech companies to allow minors to limit the category of recommendations or opt out of personalized recommendation systems that facilitate infinite scrolling.

In the past 18 months, Ms. Molak has made seven trips to Washington, and she met more than 10 congressional lawmakers during each trip.

The 61-year-old former accountant is fully dedicated to the cause through David’s Legacy Foundation, a charity she founded.

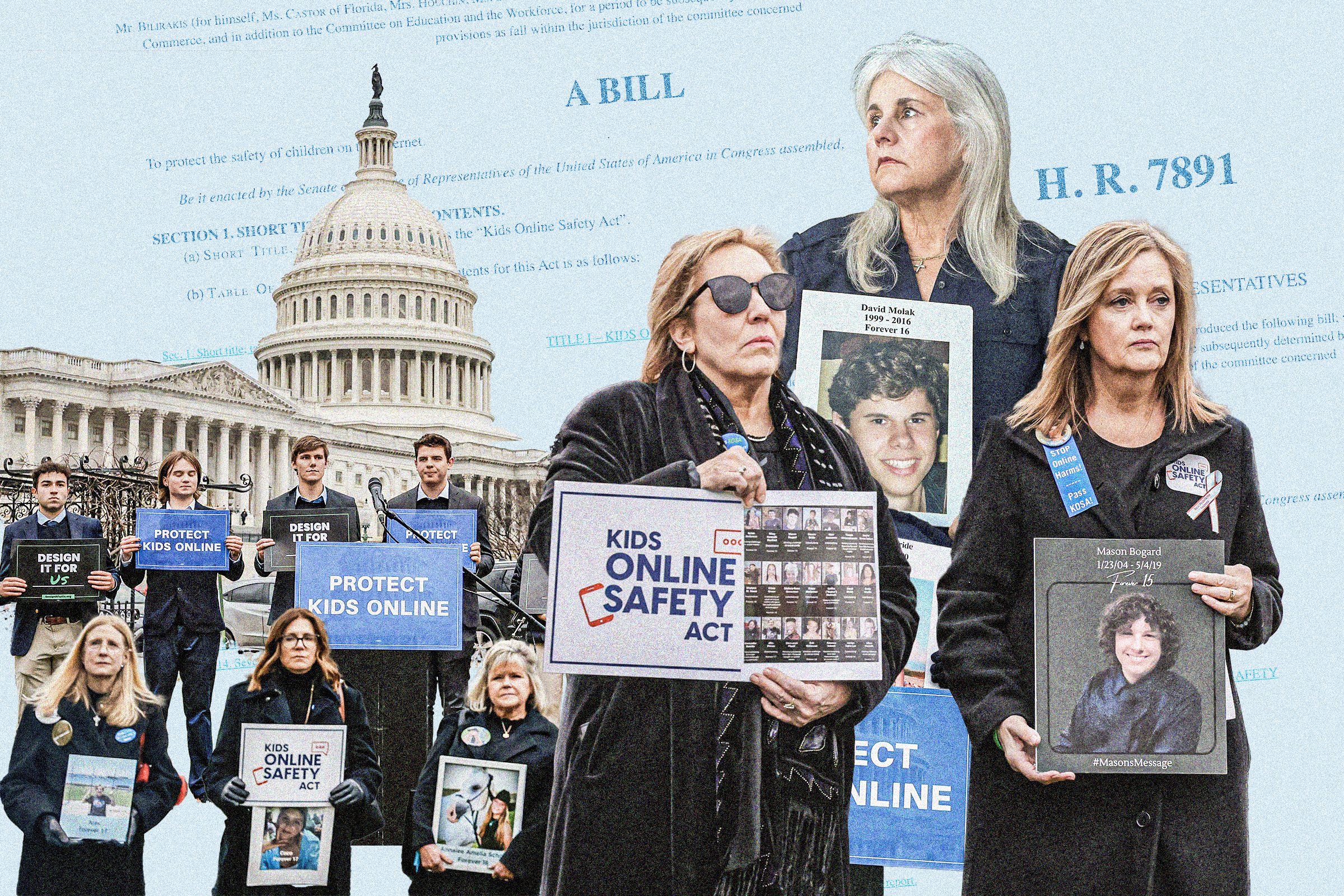

Ms. Molak and a group of mothers who lost their children because of online harms have advocated for KOSA since its 2022 version was introduced in the previous Congress.

They’ve shared their personal stories with legislators, who have shown empathy for the grieving mothers, according to several present at those meetings.

The bill was cleared by the Senate Commerce Committee in December 2023 and is slated to advance out of the House Commerce Committee soon.

Microsoft, social media platform X, and other companies have said they support the legislation.

“Senator, we support KOSA and we’ll continue to make sure that it accelerates and make sure to continue to offer community for teens that are seeking that voice,” X CEO Linda Yaccarino said at a congressional hearing on Jan. 31.

“I know that if we can get KOSA passed, we can save lives,” Ms. Molak told The Epoch Times.

She is determined to help others so no child or family will have to go through the same tragedy she did.

A teenager uses her mobile phone to access social media, in New York City on Jan. 31, 2024. Young people are often curious about aggressive content, but their brains haven't fully developed enough to consider the consequences, according to the mother of a victim. (Spencer Platt/Getty Images)

Losing David to Cyberbullying

David was athletic. Tall and lean, he was on his school’s basketball team and a non-school team through the Amateur Athletic Union.

He loved the sport that he “practically devoted his entire 15 years to since he could walk and dribble a ball,” according to his mother.

During rehab after a back injury in June 2014, he turned to social media and online gaming to fill the void.

Eight months later, Ms. Molak began noticing changes in David’s behavior.

He used his devices at night during hours when he wasn’t supposed to, and he became angry and aggressive when his parents tried to make him stop.

Then, he started using his parents’ credit card without authorization to buy online gaming accessories.

Even after he was medically cleared to play basketball again, he wasn’t interested.

“Instead, he preferred to sit behind the screen,” Ms. Molak said. “And it was at that point that we knew we were really dealing with something that we had not experienced.”

Social media addiction was still relatively new. Last year, U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy issued an advisory that excessive use of social media might lead to anxiety and depression.

But the harm wasn’t widely known 10 years ago.

David was the youngest of three sons, 5 1/2 years younger than the middle brother, Chris, who had a flip phone. But David had an iPhone.

Maurine Molak holds a picture of her son David, who died of suicide after being cyberbullied at the age of 16, at her residence in San Antonio on June 24, 2024. (Courtesy of David's Legacy Foundation)

It was offered as the newest thing at a discount. Along with the device came access to social media platforms.

Unbeknownst to Ms. Molak, David also became a target of cyberbullying.

When he told his mother about it in October 2015, it had already been three months, and it was bad. The bullying targeted David’s appearance. The messages called him an “ape” and threatened to put him “in a body bag.”

Immediately, Ms. Molak transferred David to a private school mid-semester before Thanksgiving. But the cyberbullying followed him.

She said her son’s social media addiction made him “more vulnerable to the cyberbullying and less resilient to be able to deal with it in an appropriate way.”

“He had really put his identity into who he was online through these gaming and social media personas and popularity,” she said.

“He was so beaten down that he lost hope. It had to do with this unrealistic idea of who he thought he was online and then to be the target of that. He was just crushed.”

The day before David was due back to school in January 2016, he hanged himself from a tree in the backyard.

The night before his suicide on Jan. 4, David was added to a chat with a group of anonymous people. After they sent insulting messages to him, they kicked him out of the messaging group.

Chris sat next to David as it all happened.

On Jan. 4, at about 10:30 p.m., Chris woke Ms. Molak up. David’s light was on, but he wasn’t in his bed. They started searching the house.

“I just had a sense of dread come over me,” she recalled.

She called the police and called her parents, who also live in San Antonio. Her husband was in California for knee surgery.

She drove around, looking for David. Three hours went by. Finally, the police pinged David’s phone and found that it was located in the house. The officer said he wanted to check the backyard, so she went to the floodlights by her office to turn them on.

Through the glass door of her office, she saw David in the backyard.

“When I saw him, I went tearing out of my door,“ she said. ”But the policeman caught me, and he wouldn’t let me get near David.

“I was just wailing, and my dad came running out when he heard me wailing. He was holding me down so that the policeman could go and try to get David.

“My life stopped at that moment, and it’ll never be the same.”

“It’s been eight years, and I still feel sometimes this is just a nightmare, and I’m just going to wake up, and it’s all going to be over,” she said.

Photos of David Molak sit on a shelf at the family home in San Antonio, Texas, on June 24, 2024. David became disinterested in basketball, after playing for years, after becoming addicted to social media. (Courtesy of David's Legacy Foundation)

The grieving mother said that the moment in the morning when she first wakes up and realizes that David is gone is usually the most difficult.

“I don’t sleep well, and I just miss him so much,” she said. “There’s something so unnatural and so unfair about having to live the rest of my life without my youngest child.”

Winning Over Politicians

Since late 2022, Ms. Molak and about 19 other mothers have shared their personal stories with members of congress. The women collaborated as a workgroup under Fairplay, a child advocacy nonprofit.

In January, Fairplay launched Parents for Safe Online Spaces (ParentsSOS), along with Ms. Molak’s foundation.

Josh Golin, executive director of Fairplay, a leading organization advocating KOSA, has worked with the mothers from the beginning.

“One of the things that I think happens when the parents tell their stories is that people stop being politicians and start being people, and they start thinking about the children in their own lives, their kids, grandkids, or kids that they love,” he told The Epoch Times.

According to several people present, when Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) met with the parents in early May, he choked up hearing their stories.

Joann Bogard, 58, whose son Mason died after trying the online “blackout challenge” at the age of 15, said Mr. Schumer was “very emotionally moved” in the meeting and “eager to help” in a follow-up meeting in early June.

Ms. Bogard had waited until Mason was in middle school before giving him a phone with parental controls and watchdog apps.

But she didn’t know that YouTube, a platform Mason used to improve his fishing and woodworking, fed him videos on the fatal choking challenge.

Mason tried the blackout challenge in May 2019 and accidentally killed himself because his belt buckle locked up and didn’t loosen after he lost consciousness.

He was without oxygen for too long and showed no vital activity after being on life support for three days. The Bogards donated his organs, benefiting five others.

“When people hear our stories, it makes them afraid that this is going to happen to their family. They don’t want that; they want to fix that problem,” Ms. Bogard told The Epoch Times.

“I think that’s why it’s so personal to them. Because they realize our kids are their kids. Our kids are the everyday American kids that are out there.”

Mr. Schumer was not the only senator affected by the mothers’ stories. Parents also mention Sen. Maria Cantwell (D-Wash.), chair of the Commerce Committee, as another example.

Maurine Molak (L), Joann Bogard (2nd L), Deb Schmill (R), and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) in Washington, D.C., on June 5, 2024. (Courtesy of Joann Bogard)

During a meeting in November 2022, several mothers struggled to fight their tears to speak. Ms. Cantwell rubbed their arms and backs until they could get through their stories.

“She was more like a mom than a senator,” Ms. Bogard said.

Since then, Ms. Cantwell has been a vocal supporter of the bill.

That year, she tried to bundle KOSA into a year-end spending bill but failed.

After Sens. Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.) and Marsha Blackburn (R-Tenn.) reintroduced KOSA in 2023, Ms. Cantwell’s committee passed it in December 2023, allowing a vote on the legislation on the Senate floor.

On June 20, Mr. Schumer spoke about KOSA on the Senate floor with Mr. Blumenthal, the bill’s lead Democrat sponsor.

“Like him, I have personally met with the families that have been harmed, I have seen their terrible stories, and I am committed, completely committed, to work with them to get KOSA across the finish line,” Mr. Schumer said.

“Last month, I put together a plan to get KOSA done through unanimous consent for a time agreement on the floor. I personally helped resolve issues and mitigated unintended consequences of the bill. That effort reduced the opposition but there are still holdouts.”

Mr. Schumer had been working on a time agreement, also known as a hotline vote agreement, to fast-track the bill to the Senate floor by June 20, according to parents.

The previous version of the time agreement, which expired in June, listed two hours of debate and no amendments. The process requires unanimous consent from all senators.

It’s unclear what terms are included in the new version of the time agreement. The Epoch Times contacted Mr. Schumer’s office for more information but received no reply by press time.

According to parents, Sens. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) and Rand Paul (R-Ky.) were the two lawmakers who objected to the fast-track process.

Last week, Mr. Wyden signaled that he would drop his objection to the hotlining process.

The bill has 68 cosponsors, which makes it filibuster-proof and likely to pass in the regular manner.

Mr. Paul has said his objection is related to the definition of “mental health disorder” in the bill, which he says is too broad.

In response, Mr. Golin said the definition follows the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders.

It’s unclear whether Mr. Paul will bless the new version of the hotline vote agreement, which would bring the bill up for a vote sooner.

On June 24, ParentsSOS sent a letter to Mr. Paul, urging him to drop his opposition.

The Epoch Times contacted Mr. Paul’s office for comment but received none by press time.

Mothers of victims of internet abuses and crimes attend a rally organized by Accountable Tech and Design It For Us to hold tech and social media companies accountable for taking steps to protect kids and teens online, in Washington on Jan. 31, 2024. (Jemal Countess/Getty Images for Accountable Tech)

Surgeon General’s Warning

Dr. Murthy earlier this month called for a warning label for social media platforms, similar to the warning on tobacco products.

“It is time to require a surgeon general’s warning label on social media platforms, stating that social media is associated with significant mental health harms for adolescents,” he wrote in a New York Times op-ed.

In his piece, he recalled meeting Lori Schott, whose daughter Annalee took her own life at age 18 in 2020 because of online self-harm content.

The meeting occurred in March 2023, when Dr. Murthy visited the Children’s Hospital in Denver to speak about the youth mental health crisis.

Ms. Schott lives in Colorado, and Sen. Michael Bennet (D-Colo.) brokered the meeting.

She took copies of Annalee’s journals to show Dr. Murthy the effect of social media on the teenager’s mental health.

“This was information I had not even shared with my family or my husband because we were so devastated,” she told The Epoch Times. “I was in tears.”

She said Dr. Murthy was “empathetic and supportive.”

He listened to Ms. Schott for more than an hour.

She knew that he had already worked on the issue because two months later, he issued an advisory about social media’s harm to young people’s mental health.

“The thing I look back at it with tears and gratitude is that if I had heard the surgeon general’s warnings, the first one that he gave, or even the second one about warning labels on social media, I would have the grounds to parent different and to understand what was going on with Annalee’s mental health and the depth of the dangers of what these platforms were feeding our kids,” the mother said.

Dr. Murthy’s office declined to comment on the meeting.

If enacted, KOSA would authorize the warning Dr. Murthy proposed.

Three of four voters support the social media warning label, according to a Quinnipiac University poll released June 26.

Educating Self and Educating Senators

One thing the mothers have in common is that they have learned a great deal about social media because of their tragedies.

Ms. Bogard said she had learned much about algorithms in the past five years.

Joann Bogard, mother of an internet challenge victim, Mason Bogard, speaks during a rally to hold tech and social media companies accountable for taking steps to protect kids and teens online, in Washington on Jan. 31, 2024. (Jemal Countess/Getty Images for Accountable Tech)

“Companies have deliberately designed the algorithms to feed the most intense content to [children],” she said.

Young people, she said, cannot resist the feed of “aggressive content—bullying, fighting, suicidal ideation, anything hypersensitive like that” because they are curious, and their brains haven’t developed enough to consider the consequences.

“It’s going to feed whatever keeps their eyes on the screen,” she said.

Ms. Bogard said she likes that the KOSA bill addresses algorithms, or design features, as they’re termed in the bill.

She said of the mothers’ first meeting with senators in 2022, “They didn’t really have a good idea of how algorithms work and how social media companies were deceiving and manipulating our children.”

However, at a hearing in January, senators had many back-and-forths with tech company executives.

Ms. Bogard said the lawmakers demonstrated a deeper grasp of the design features, the algorithms, and the tech companies’ ability to control what users could see and do on their platforms.

“You could tell they were more in tune and more in line with what was actually going on this time. A lot of that, I really feel, has to do with the depth of the parents’ information that we’ve been giving them,” she said.

Mr. Golin of Fairplay said the parents were doing an “amazing job.”

“I think some people in Congress are heartbroken when they hear their story and want to do something for them, and some people in Congress are scared of these parents,” he said.

“Nobody wants to be seen as being on the side of Meta and Snapchat over grieving parents.”

KOSA Is a ‘First Step’

The parents are already looking beyond KOSA.

KOSA is a “first step,” Ms. Schott said.

“I think our work in our children’s names is to save other children and demand real change,” she said.

Young activists hold up signs during a rally to hold tech and social media companies accountable for taking steps to protect kids and teens online, in Washington on Jan. 31, 2024. (Jemal Countess/Getty Images for Accountable Tech)

Ms. Bogard said that she would continue to monitor the implementation of KOSA after it passes.

They expect the conversation about social media harm to continue and are determined to continue working to help other families and children.

“I understand what it’s like when you have a child who’s in crisis, and you feel like the world is spinning really, really fast, but you’re moving in slow motion,” Ms. Molak said. “I could relate to that.”

She said Mr. Schumer offered to host a “celebratory signing” when the bill becomes law.

“We’ve lost our children. This is not a victory for us. This is just what we have to do in order to protect other children so that no other parent has to walk in our shoes,” Ms. Molak said.

“I think [Mr. Schumer] realized that. He was compassionate and gave us multiple reassurances that this was going to come to the floor. ... We know it will pass.”

To get help with addiction or mental health issues visit SAMHSA.gov