With former Venezuelan leader Nicolás Maduro awaiting trial in federal custody in New York City on narco-terrorism charges and U.S. President Donald Trump vowing that the United States will run the country until there is a “proper transition,” the world is witnessing the sharpest manifestation yet of a generational U.S. foreign policy shift which has been taking shape since Trump returned to the White House last year.

Under the “Trump Corollary” to President James Monroe’s 1823 policy that declared the Western Hemisphere a distinct sphere of U.S. influence, removing Maduro from office and seizing control of Venezuela’s oil resources are among the latest and greatest geopolitical maneuvers as part of a renewed focus on affairs closer to America’s shores, most notably and immediately in the Caribbean Basin.

“After years of neglect, the United States will reassert and enforce the Monroe Doctrine to restore American preeminence in the Western Hemisphere, and to protect our homeland and our access to key geographies throughout the region,” the White House stated in November as it unveiled its new National Security Strategy.

The Trump administration’s pivot to Latin America “is a common-sense and potent restoration of American power and priorities, consistent with American security interests,” the document states.

Operation Southern Spear has been in the spotlight off Venezuela since September, with the USS Gerald Ford, the world’s largest aircraft carrier, and the USS Iwo Jima, an amphibious assault ship, as its centerpiece. The massive ships are the most visible components of a campaign that destroyed drug-smuggling speedboats, imposed a selective blockade on sanctioned oil tankers, and led to the Jan. 3 U.S. military operation that captured Maduro.

Other key, yet more subtle, regional developments are unfolding in the Caribbean as the Trump administration implements its new strategy. Pressure on Venezuela is having an immediate impact on neighboring Guyana and Cuba, but its longer-term aim is to thwart “non-hemispheric” actors from accessing resources beyond just the Caribbean, from as far north as Greenland to as far south as Tierra del Fuego.

Driving the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) from the Western Hemisphere, or at least diminishing its influence, is the primary aim of this new National Security Strategy.

As Adm. Alvin Holsey, former U.S. Southern Command commander, told the Senate Armed Forces Committee in a Feb. 13, 2025, hearing, Latin America contains one-third of the globe’s renewable freshwater, 30 percent of its forests, 31 percent of its fisheries, 20 percent of its crude oil, and 25 percent of its strategic metals. It grows half the world’s soybeans, grows 30 percent of its sugar, and boasts 60 percent of known lithium deposits.

China has become South America’s largest source of infrastructure investment and second-largest trading partner, increasing trade to $450 billion in 2022 from $18 billion in 2002 and inducing 22 of the 31 nations within Southern Command’s area of responsibility to join the CCP’s Belt and Road Initiative.

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi (R) and Venezuela’s Foreign Minister Yvan Gil shake hands before their meeting at the Diaoyutai State Guesthouse in Beijing on May 12, 2025. (Florence Lo/POOL/AFP via Getty Images)

Cuffing CCP Advances

In a June 2025 EpochTV interview, Joseph Humire, who is now acting deputy assistant secretary of war for the Western Hemisphere, said the United States lacked a grand strategy to counter the expansion of Chinese influence in Latin America.

China capitalized on U.S. “neglect” in the region, he said. Twenty years ago, China was a trade partner of only three countries in South America. Today, China is “probably the top trade partner of most of South America,” he said.

During a March 2024 hearing of the House Armed Services Committee, Rep. Joe Wilson (R-S.C.) said, “CCP-backed companies currently own or operate mines in Mexico, Argentina, Peru, and Venezuela, electrical grids in Peru and Chile, 5G wireless systems in Costa Rica and Bolivia, Brazil, and Mexico, space launch and satellite tracking facilities in Peru, Venezuela, Bolivia, [and] Argentina, as well as 40 ports across 16 Latin American and Caribbean countries.”

Trump’s return to the White House began to challenge China’s expansion plans for the region. Under pressure from Washington, Hong Kong-based CK Hutchison, which owns 90 percent of the company that operates the Panama Canal, in March agreed to sell its shares and hand over operations of the two ports to a group led by U.S. investment company BlackRock.

The Hong Kong-flagged LPG tanker is seen leaving the Panama Canal on the Pacific side near Panama City on July 28, 2025. Hong Kong-based CK Hutchison, which owns 90 percent of the company that operates the Panama Canal, in March 2025 agreed to sell its shares and hand over operations of the two ports to a group led by U.S. investment company BlackRock. (Martin Bernetti/AFP via Getty Images)

Securing the Panama Canal was the first implementation of the foreign policy shift to the Western Hemisphere, said Gregory Copley, president of the Washington-based International Strategic Studies Association and editor-in-chief of Defense & Foreign Affairs.

Resolving the “Venezuela situation” is step two, he told The Epoch Times.

“This is a problem largely because [Venezuela has] been allowed to become an enclave for action against the United States by China, Russia, Cuba, and Iran,” he said.

“The reality is, Trump is now driving the Chinese out of the Caribbean Basin,” he said.

Renewed Regional Focus

Even before formally articulating the new national security strategy in November, the president determined that the United States would be actively engaged in the Western Hemisphere, issuing a day one executive order on Jan. 20 stating that Mexican and South American drug cartels smuggling fentanyl, cocaine, and narcotics were waging “a campaign of violence and terror.”

The Trump Corollary is the first Monroe Doctrine update since 1904, when President Theodore Roosevelt, issuing what came to be known as the Roosevelt Corollary, declared that the United States would intervene as an “international police power” in Latin America to quell unrest and prevent European interference.

In line with this, Trump maintains that he can authorize the Pentagon to engage in “non-international armed conflict” with terrorists without congressional endorsement. Democrats, and some Republicans, disagree.

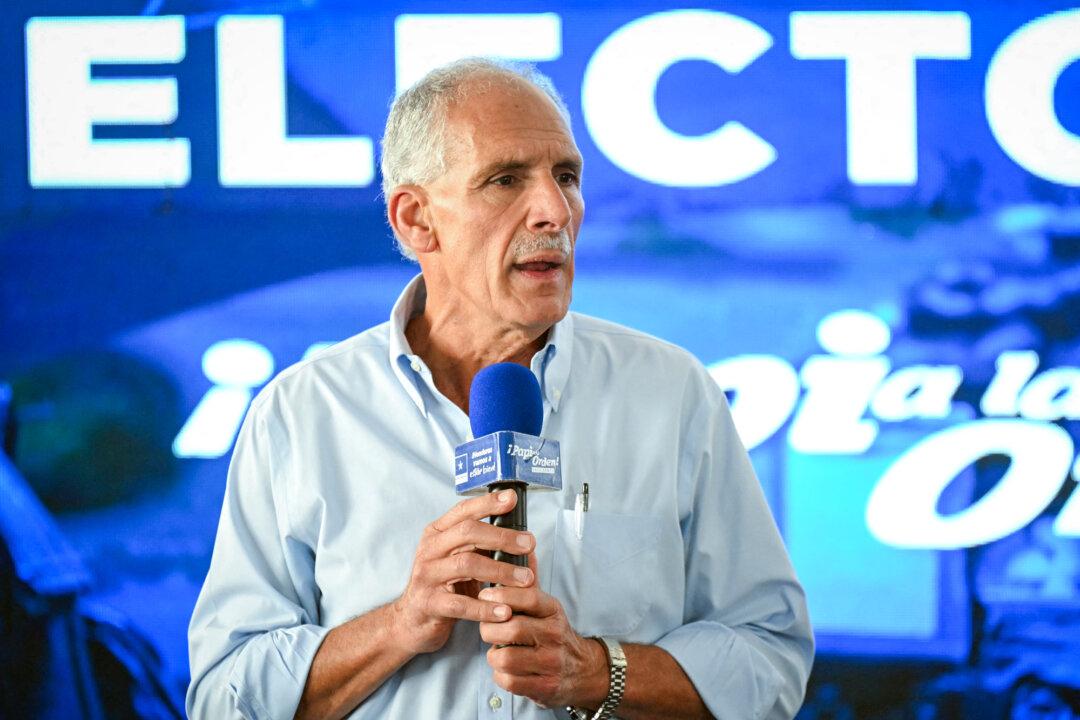

The president has aggressively supported ideologically aligned leaders and candidates across Central and South America, backing Nasry Asfura’s presidential campaign in Honduras and Argentine President Javier Milei’s party in midterm elections. He later supported Milei’s administration with a $20 billion currency swap to stabilize the Argentine peso.

(Left) Honduras presidential candidate of the National Party Nasry Asfura speaks during a press conference in Tegucigalpa, Honduras, on Dec. 1, 2025. (Right) Argentine President Javier Milei (C) arrives at the Nobel Peace Prize ceremony at Oslo City Hall in Oslo, Norway, on Dec. 10, 2025. President Donald Trump has aggressively supported ideologically aligned leaders and candidates across Central and South America, backing Asfura’s presidential campaign and Milei’s party in midterm elections. (Marvin Recinos/AFP via Getty Images, Ole Berg-Rusten/NTB/AFP via Getty Images)

Trump has also taken a personal interest in lobbying on behalf of former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, sentenced in September to serve 27 years in prison for orchestrating a failed 2022 coup attempt. The Trump administration has imposed tariffs and sanctions on Brazil in an attempt to pressure Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva to release Bolsonaro and allow him, perhaps, to run for president in 2026.

The Trump administration has supported conservative Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele’s use of the Terrorism Confinement Center as a maximum security prison where illegal immigrants arrested in the United States and deemed to be gang members are deported and detained.

As the United States tightened its vise on Venezuela, Trump allies in Argentina and El Salvador expressed support for the effort to oust Maduro, while leaders in Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico opposed what they define as interference in the region’s affairs and autonomy.

In a Dec. 17, 2025, House hearing, Mexico was praised for its increased border security and efforts to curb drug smuggling but criticized for shipping oil to Cuba to supplement the loss of petroleum exports from Venezuela. Several Republicans said that if Mexico does not do more to battle cartels, the U.S. military may step in.

Trump reiterated that threat on Jan. 4, stating that the United States might have “to do something with Mexico” and warning Colombian President Gustavo Petro that his nation is also on the Pentagon’s radar. Trump mused that pursuing military actions against Colombia “sounds good” to him.

The reach of the expanded Monroe Doctrine has extended as far as Greenland, which the president has said is surrounded by Russian and Chinese ships.

He told reporters on Jan. 4, “We need Greenland from the standpoint of national security, and Denmark is not going to be able to do it.”

President Donald Trump, Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick (L), and Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) (C) speak to the media aboard Air Force One enroute to Washington on Jan. 4, 2026. (Joe Raedle/Getty Images)

Cuba in Crosshairs

With the Panama Canal secure and Maduro no longer ruling in Caracas, the Trump administration’s early phase focus in the Caribbean also puts the spotlight on Cuba.

Cuba’s state-owned trading company Cubametales has contracted with Venezuela’s state-owned oil company PDVSA to import up to 53,000 barrels of crude per day since at least 2019, according to the U.S. State Department. Much of that is sold for sorely-needed hard currencies, often to Chinese buyers, before it ever reaches the island.

This arrangement was uncovered when the crude oil tanker Skipper left Caracas on Dec. 4 with almost 2 million barrels of Venezuelan crude allegedly bound for the Cuban port of Matanzas, as documented by ship-tracking sites and the maritime data firm Kpler. But Skipper, illegally flying a Guyanese flag, transferred only 50,000 barrels to a smaller Cuban tanker, Neptune 6, before heading east into the Atlantic, where it was boarded and seized on Dec. 10 by U.S. special forces.

The exchange illustrates a close relationship between Venezuela and Cuba, which also imports rice, beans, and other food staples from Caracas. Cuban President Miguel Díaz-Canel’s regime was key in keeping former Venezuelan leader Hugo Chávez and then Maduro in power for decades, with as many as 30,000 Cuban doctors, nurses, sports instructors, security advisers, and intelligence agents in the country.

Cuban intelligence and bodyguards were responsible for “coup-proofing” Maduro by monitoring the Venezuelan army and safeguarding his personal security. Cuba announced on Jan. 4 that 32 of those security officers were killed in the U.S. raid on Maduro’s compound.

A firefighter walks past a destroyed anti-aircraft unit at La Carlota military air base, after President Donald Trump said the United States had struck Venezuela and captured its leader, Nicolás Maduro, in Caracas, Venezuela, on Jan. 3, 2026. (Leonardo Fernandez Viloria/Reuters)

The U.S. naval task force in the southern Caribbean is not only focused on Venezuela, Anders Corr, publisher of the Journal of Political Risk and principal at Corr Analytics in Pittsburgh, told The Epoch Times.

“It’s about Cuba, too,” said Corr, who predicted before the Jan. 3 raid that the United States would capture Maduro and haul him away in a helicopter without the need of an invasion.

“The aircraft carrier gives Trump options in the Caribbean region. He can use that aircraft carrier to pressure Venezuela, Mexico, and Cuba, all at the same time.”

Corr said he is uncertain that such pressure will drive Cuba’s communist regime from power, noting that while food and medicine shortages sparked 2021 protests, “it really wasn’t something big enough to overthrow the government” and that despite growing scarcities, “the government in Cuba just seems to be propagandizing” Cubans into seeing the United States as their tormentor.

Copley said under sustained U.S. pressure, Cuba’s days as a communist bastion may be numbered.

“It gets to be connected with everything else,” he said. “How long is the government of Cuba going to last? The answer to that is not very long, either. So you’ve got all these things falling apart.”

A man sells cookies displayed on an old American car in the street on the fourth anniversary of anti-government protests in Havana, Cuba, on July 11, 2025. With the Panama Canal secure and Maduro no longer ruling in Venezuela's capital of Caracas, the Trump administration's focus on the Caribbean also puts the spotlight on Cuba. (Yamil Lage/AFP via Getty Images)

Guyana’s Essequibo

With Maduro gone and the Venezuelan government hobbled, the citizens of its neighbor Guyana could be the most relieved. The countries have been embroiled in a 180-year-old border dispute, used by the Maduro regime as an excuse to menace the sparsely populated, Idaho-sized former British colony with naval intrusions and troop buildups.

Venezuela’s agitation over Essequibo, a region that spans two-thirds of Guyana, has increased significantly since ExxonMobil discovered oil in the Stabroek Block off its shores in 2008. The Punta Playa deposit contains an estimated 11 billion barrels of oil, making it one of the 21st century’s largest petroleum finds, producing more than 500,000 barrels daily. Venezuela, by comparison, has an estimated 300 billion barrels of oil reserves but only produces 1 million barrels per day.

In November 2023, Maduro announced a “people’s vote” to “respond to the provocations of Exxon, the U.S. Southern Command, and the president of Guyana.” A Dec. 3, 2023, referendum asking Venezuelans to annex Essequibo, even by force, was approved.

In April 2024, Maduro signed a bill formally creating the Venezuelan state of “Guayana Esequiba” and began enlarging an army base on a Cuyuni River island that Guyana claims is illegally occupied. There have been numerous incidents along the border since.

A sign reads “The Essequibo is ours” on the banks of the Cuyuni River, which separates Venezuela from the Essequibo region, in San Martín de Turumbang, Venezuela, on May 26, 2025. Venezuela and Guyana have long been embroiled in a border dispute over the mineral‑rich Essequibo territory, which Guyana administers but Venezuela continues to claim. (Pedro Mattey/AFP via Getty Images)

A U.S. delegation led by senior Pentagon adviser Patrick Weaver and Humire met with Guyanese President Irfaan Ali in the nation’s capital, Georgetown, and returned on Dec. 10 to Washington with an agreement to expand military cooperation between the two countries.

Although Guyanese leaders deny it, some speculate that the English-speaking country perched on eastern Caribbean sea lanes, where the United States operated a naval station and airfield during World War II, could be an ideal site for a base to anchor the shift to the south.

“The Guyana aspect is one of the hidden gems in this, as far as the U.S. is concerned, because U.S. [companies] have the majority of the offshore energy reserves off Essequibo,” Copley said. “I think the Guyanese would welcome increased cooperation with the United States.”

Corr agreed.

“It would certainly make sense for Guyana to request a U.S. military base because that would give Guyana’s oil resources, other energy resources, a protection it won’t get anywhere else,” he said, before noting that there could be a few qualifications.

“Trump is very much over [the United States] spending money to protect other countries without getting something for it,“ he said. ”So he would probably ask for some kind of a concession on the part of Guyana for that sort of protection. And he might very well get it.”