Cities and states across the United States have filed more than 30 lawsuits against energy companies, accusing them of causing climate-related issues and bad weather, according to a June report by Climate in the Courts.

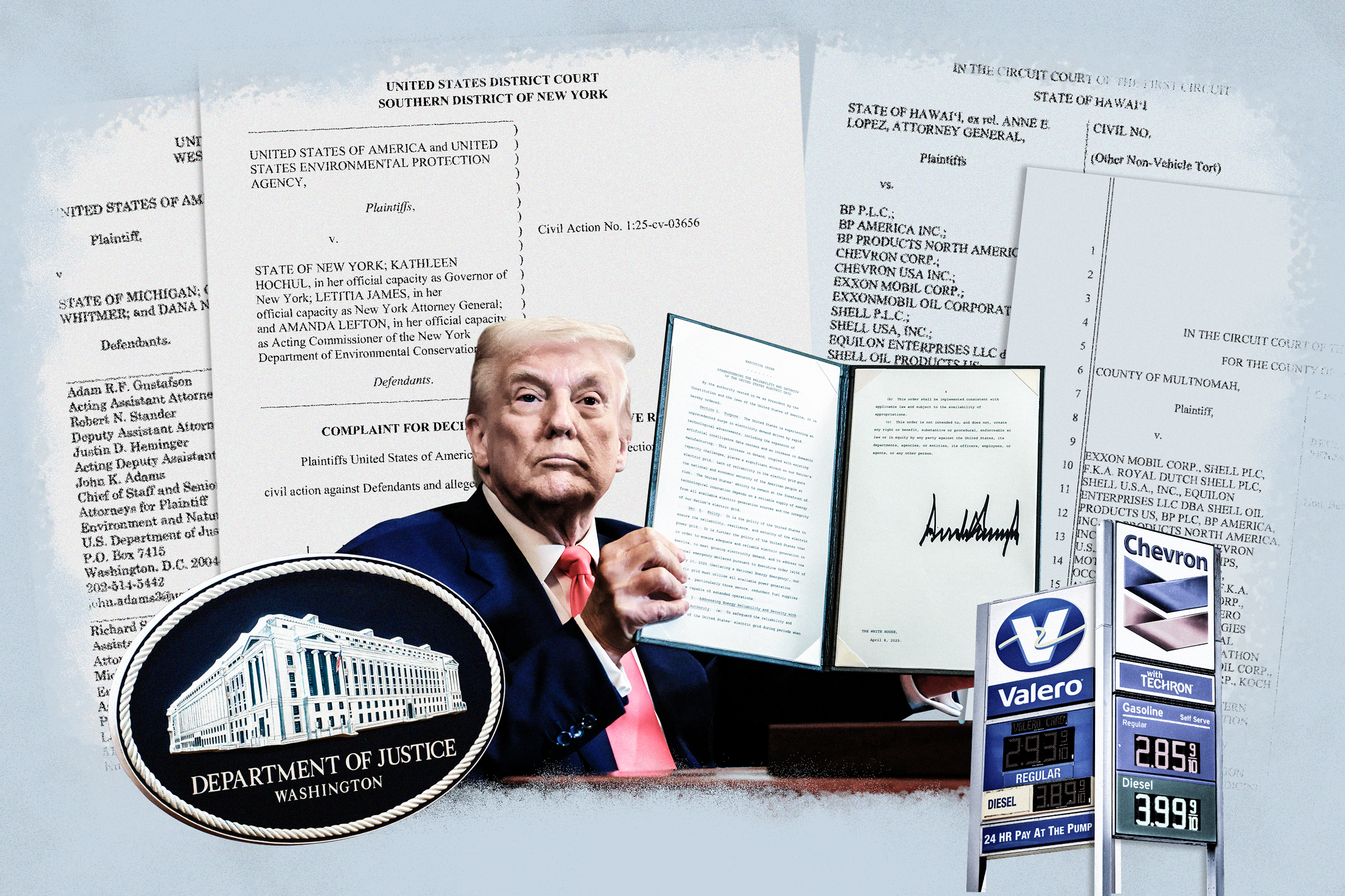

Simultaneously, the Trump administration is carrying out a campaign to counter the growing pile of climate lawsuits.

President Donald Trump signed an executive order on April 8 that directed the attorney general’s office to “take all appropriate action” to stop state-level climate litigation that could be considered unconstitutional or preempted by federal law.

The order states that state-level climate lawsuits threaten to increase energy costs for all Americans, curtail the U.S. energy supply, and undermine federalism.

As a result of the executive order, on April 30, the Justice Department (DOJ) filed preemptive lawsuits against Hawaii and Michigan in an attempt to stop the states from filing suits of their own.

“At a time when States should be contributing to a national effort to secure reliable sources of domestic energy, Hawaii is choosing to stand in the way,” the DOJ stated in its lawsuit against Hawaii. “This Nation’s Constitution and laws do not tolerate this interference.”

The language in the Michigan lawsuit was similar.

O.H. Skinner, executive director of the Alliance for Consumers, said federal officials are “trying to stop what hasn’t started yet, which is a different problem than dealing with the cases that are already ongoing.”

“Clearly the Trump administration thinks that this [climate litigation] is effectively an attempt to gain control of our entire energy sector nationwide through little courtroom actions,” Skinner told The Epoch Times.

Undeterred by the DOJ, Hawaii filed a climate lawsuit the next day. Another lawsuit out of Multnomah County, Oregon, alleged that energy companies owe the county $50 million in existing damages, $1.5 billion in future damages, and another $50 billion to establish an abatement.

Defendants in that suit include the American Petroleum Institute; Anadarko Petroleum; BP; Chevron; ConocoPhillips; Exxon Mobil; Koch Industries; Marathon Petroleum; McKinsey & Co.; Motiva; Occidental Petroleum; Peabody Energy; Shell; Space Age Fuel; Total Specialties USA; Valero Energy; and Western States Petroleum Association. The county alleges that the companies misled the public and created a “heat dome” over its residents.

“These businesses knew their products were unsafe and harmful, and they lied about it,” Multnomah County Board of Commissioners Chair Jessica Vega Pederson said in a statement.

President Donald Trump speaks alongside coal and energy workers during an executive order signing ceremony in the East Room of the White House on April 8, 2025. The Trump administration is countering a wave of state-level climate lawsuits filed against energy companies. (Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images)

DOJ Cites Federal Supremacy

The DOJ has supported energy companies in their efforts to have municipal lawsuits moved out of local jurisdictions and into federal courts, arguing that federal regulatory authority over emissions preempts state law.

In September, U.S. Deputy Solicitor General Sarah Harris filed a brief with the Supreme Court regarding Suncor Energy and other energy companies’ petition regarding a Boulder County, Colorado, lawsuit. The brief argues that local authorities are limited by the Constitution to their own borders and that “Colorado therefore may not apply its law to the companies’ conduct outside the State.”

Even if states could claim authority beyond their borders, Harris wrote, Colorado’s mandate to regulate emissions would be preempted by federal authority, established by the 1970 Clean Air Act, “which precludes any such role for a single State.”

To date, judges have dismissed many of the climate lawsuits.

In January, the New York Supreme Court dismissed a case brought by New York City against BP, Exxon Mobil, and Shell. And in 2024, Baltimore Judge Videtta Brown dismissed the city’s climate suit and argued that federal law governs the regulation of air pollution, which was the intent behind the lawsuit.

“The explanation by Baltimore that it only seeks to ... hold defendants accountable for a deceptive misinformation campaign is simply a way to get in the back door what they cannot get in the front door,” Brown said.

Customers fuel up at a gas station in Los Angeles on March 25, 2025. Plaintiffs say the suits have a goal of cutting greenhouse gas emissions by increasing energy prices and reducing demand. (John Fredricks/The Epoch Times)

Critics of climate-related lawsuits say plaintiffs prefer to keep the cases in local courts, where they may have a better chance of success with a more sympathetic judge or jury.

“Apart from the realities that no evidence supports the nuisance assertions, and ‘failure to warn’ assumes past knowledge—that not even the [U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in its first assessment] assumed—it is difficult to envision the appellate courts allowing such arguments to prevail, even with juries involved,” Benjamin Zycher, senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, told The Epoch Times.

However, state supreme courts in Massachusetts, Hawaii, and Colorado denied energy companies’ motions to dismiss and allowed cases to proceed to trial. Additionally, several lawsuits in Maryland, brought by Anne Arundel County and the cities of Baltimore and Annapolis, are currently before the state’s supreme court.

On Oct. 6, plaintiffs’ attorney Vic Sher told Maryland Supreme Court judges that his lawsuits had nothing to do with regulating greenhouse gas emissions and therefore were not preempted by federal authority.

“It does not involve capping, regulating, or limiting emissions by the defendants or anybody,” Sher said. “It doesn’t involve changing pollution control measures or installing equipment or anything like that by these defendants or anyone else.”

He said the lawsuits are instead about residents getting compensation for “nuisance, trespass and failure to warn.”

David Bookbinder, a plaintiff’s attorney in a Colorado climate lawsuit, said the suits do have a regulatory goal of cutting greenhouse gas emissions by increasing energy prices and reducing demand.

The Colorado Supreme Court chambers in the state capitol in Denver. In September, U.S. Deputy Solicitor General Sarah Harris filed a brief with the Supreme Court saying that Colorado cannot apply its laws to energy companies’ conduct outside the state. (Library of Congress)

“Tort liability is an indirect carbon tax,” Bookbinder said at an Oct. 10 Federalist Society webinar on climate litigation.

“You sue an oil company, an oil company is liable, the oil company then passes that liability on to the people who are buying its products. In some sense, it is the most efficient way—the people who buy those products are now going to be paying for the cost imposed by those products.”

Options for Trump Administration

Experts say there are several paths the Trump administration can take to combat climate lawsuits.

“They might go to Congress—a difficult path—or they might sue on their own on some grounds,” Zycher said.

Other options are continuing to submit amicus briefs in existing court cases or enacting new regulations to “rein in the litigation game,” he said.

Legal analysts draw parallels between climate lawsuits and tobacco lawsuits, in which 45 tobacco companies settled with states in 1998, agreeing to pay them more than $200 billion dollars over 25 years.

This nationwide settlement occurred after a jury awarded $400,000 in 1998 to a New Jersey resident who claimed that tobacco companies had failed to warn him about the dangers of smoking.

Cigarettes continued to be sold after the settlement, but at significantly higher prices. This, combined with a public education campaign about the harms of smoking, substantially reduced cigarette consumption.

(L–R) Loews Corp. CEO Laurence Tisch, Philip Morris Chairman Geoffrey Bible, U.S. Tobacco CEO Vincent Gierer Jr., RJR Nabisco CEO Steven Goldstone, and Brown & Williamson Chairman Nicholas Brooks are sworn in before testifying to the House Commerce Committee in Washington on Jan. 29, 1998. Legal analysts draw parallels between climate lawsuits and tobacco lawsuits, in which 45 companies settled with states in 1998, agreeing to pay them more than $200 billion over 25 years. Cigarettes remained on the market following the lawsuit, but at much higher prices. (Jessica Persson/AFP via Getty Images)

Similarly, the strategy for climate lawsuits appears to be to win a few local cases and compel energy companies to settle the other suits rather than risk additional punitive damages in court.

However, according to Skinner, there is little comparison between cigarettes and the need for energy to drive cars, heat homes, and generate electricity.

“When tobacco companies settled, it was passed on to consumers in the way that cigarettes got more expensive,” Skinner said. “[With climate lawsuits], it would be passed on to consumers in the sense that a lot of energy just disappears.

“If one county in Oregon says that the nuisance is affecting them to the tune of $50 billion, this actually looks like an attempt to bankrupt the energy companies in America under the guise of, ‘We just want you to fix the nuisance.’”