Academics and cybersecurity professionals warn that a wave of fake scientific research created with artificial intelligence (AI) is quietly slipping past plagiarism checks and into the scholarly record. This phenomenon puts the future credibility of scientific research at risk by amplifying the long-running industry of “paper-mill” fraud, experts say.

Academic paper mills—fake organizations that profit from falsified studies and authorship—have plagued scholars for years, and AI is now acting as a force multiplier.

Some experts have said that structural changes, not just better plagiarism checkers, are necessary to solve the problem.

The scope of the problem is staggering; more than 10,000 research papers were retracted globally in 2023, according to Nature.

Manuscripts fabricated using large language models (LLMs) are proliferating across multiple academic disciplines and platforms, including Google Scholar, the University of Boras found. In a preprint posted on medRxiv in September, researchers at the University of Surrey observed that LLM tools—such as ChatGPT, Gemini, and Claude—can generate plausible research that passes standard plagiarism checks.

In May, Diomidis Spinellis, a computer science academic and professor at the Athens University of Economics and Business, published an independent study of AI-generated content found in the Global International Journal of Innovative Research after discovering that his name had been used in a false attribution.

Spinellis noted that just five of the 53 articles examined with the fewest in-text citations showed signs of human involvement. AI detection scores confirmed “high probabilities” of AI-created content in the remaining 48.

The ChatGPT app and website are displayed on a phone and a laptop in an illustration photo from 2025. Academics and cybersecurity experts warn that AI-generated fake research is slipping past plagiarism checks and entering the scholarly record, threatening the credibility of scientific work. (Justin Tallis/AFP via Getty Images)

In an analysis of AI-generated “junk” science published on Google Scholar, Swedish university researchers identified more than 100 suspected AI-generated articles.

Google did not respond to The Epoch Times’ request for comment.

The Swedish study authors said a key concern with AI-created research—human-assisted or otherwise—is that misinformation could be used for “strategic manipulation.”

“The risk of what we call ‘evidence hacking’ increases significantly when AI-generated research is spread in search engines,” study author Bjorn Ekstrom said. “This can have tangible consequences as incorrect results can seep further into society and possibly also into more and more domains.”

The Swedish university team stated that even if the articles are withdrawn, AI papers create a burden for the already hard-pressed peer review system.

Far-Reaching Consequences

“The most damaging impact of a flood of AI-generated junk science will be on research areas that concern people,” Nishanshi Shukla, an AI ethicist at Western Governors University, told The Epoch Times.

Shukla said that when AI is used to analyze data, human oversight and analysis are critical.

“When the entirety of research is generated by AI, there is a risk of homogenization of knowledge,” she said.

“In [the] near term, this means that all research [that] follows similar paths and methods is corrupted by similar assumptions and biases, and caters to only certain groups of people. In the long term, this means that there is no new knowledge, and knowledge production is a cyclic process devoid of human critical thinking.”

A person views an example of a “deepfake” video manipulated using artificial intelligence, by Carnegie Mellon University researchers, in Washington on Jan. 25, 2019. A key concern with AI-created research—human-assisted or otherwise—is that misinformation could be used for “strategic manipulation,” researchers said. (Alexandra Robinson/AFP via Getty Images)

Michal Prywata, co-founder of AI research company Vertus, also said the AI fake science trend is problematic—and the effects are already visible.

“What we’re essentially seeing right now is the equivalent of a denial-of-service attack,” Prywata told The Epoch Times. “Real researchers drowning in noise, peer reviewers are overwhelmed, and citations are being polluted with fabricated references. It’s making true scientific progress harder to identify and validate.”

In his work with frontier AI systems, Prywata has seen the byproducts of mass-deployed LLMs up close, which he said he believes is at the heart of the issue.

Nathan Wenzler, field chief information security officer at Optiv Security. (Courtesy of Optiv Security)

“This is the predictable consequence of treating AI as a productivity tool rather than understanding what intelligence really is,” he said. “LLMs, as they are now, are not built like minds. These are sophisticated pattern-matching systems that are incredibly good at producing plausible-sounding text, and that’s exactly what fake research needs to look credible.”

Nathan Wenzler, chief information security officer at Optiv, said he believes that the future of public trust is at stake.

“As more incorrect or outright false AI-generated content is added into respectable journals and key scientific reviews, the near- and long-term effects are the same: an erosion of trust,” Wenzler told The Epoch Times.

Wenzler said that from the security end, Wenzler said universities now face a different kind of threat when it comes to the theft of intellectual property.

“We’ve seen cyberattacks from nation-state actors that specifically target the theft of research from universities and research institutes, and these same nation-states turn around and release the findings from their own universities as if they had performed the research themselves,” he said.

Ultimately, Wenzler said this could have a huge financial effect on the organizations counting on grants to advance legitimate scientific studies, technology, health care, and more.

Research scientists develop a replicating RNA vaccine at a microbiology lab at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle on Dec. 10, 2020. Experts warn that universities now face heightened risks of intellectual property theft from AI-augmented nation-state cyberattacks. (Karen Ducey/Getty Images)

Wenzler described a possible real-world example: “AI could easily be used to augment these cyberattacks, modify the content of the stolen research just enough to create the illusion that it is unique and separate content, or create a false narrative that existing research is flawed by creating fake counterpoint data to undermine the credibility of the original data and findings.

“The potential financial impact is massive, but the way it could impact advancements that benefit people across the globe is immeasurable.”

Prywata pointed out that a large segment of the public already questions academia.

“What scares me is that this will accelerate people questioning scientific institutions,” he said. “People now have evidence that the system can be gamed at scale. I’d say that’s dangerous for society.”

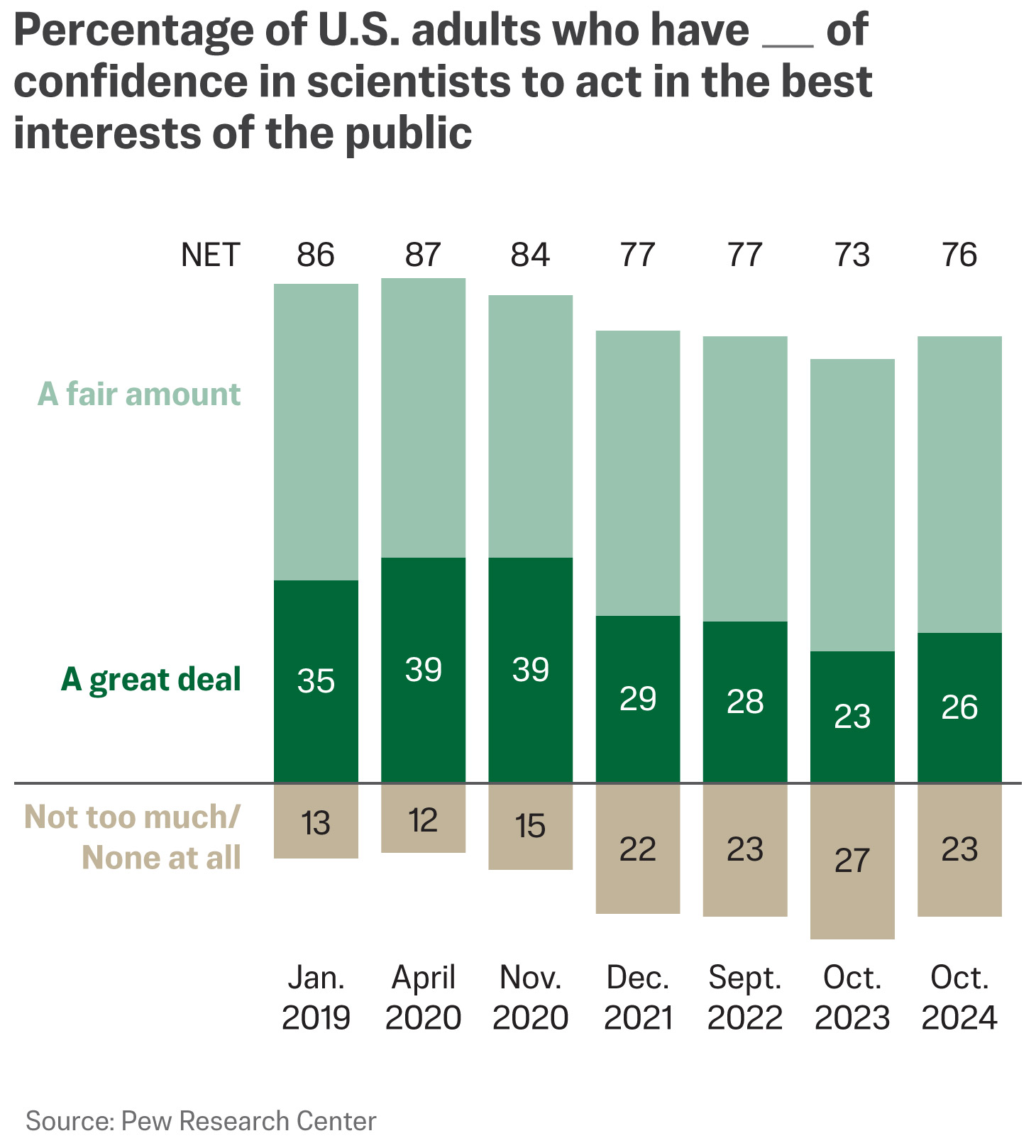

The stream of fake AI-generated research papers is coming at a time when public trust in science remains lower than before the COVID-19 pandemic. A 2024 Pew Research Center analysis found just 26 percent of respondents have a great deal of confidence in scientists to act in the best interests of the public. Fifty-one percent stated they have a fair amount of confidence; by contrast, the number of respondents who expressed the same level of confidence in science in 2020 was 87 percent.

At the same time, Americans have grown distrustful of advancements in AI. A recent Brookings Institution study found that participants exposed to information about AI advancements became distrustful across different metrics, including linguistics, medicine, and dating, as compared with non-AI advancements in the same areas.

An illustration of Anthropic, an American AI company, on Aug. 1, 2025. Michal Prywata warns that published AI-fabricated data can train new models, creating a misinformation feedback loop. (Riccardo Milani/Hans Lucas/AFP via Getty Images)

Finding Solutions

Shukla said she believes that the tide of AI-fabricated research is the result of academic pressure to publish new papers constantly.

“In such circumstances, when the number of papers and citations dictates one’s academic career, AI-fabricated research serves as a fast way of getting ahead,” she said. “Thus, the first step in stopping AI-fabricated research is releasing the publication pressure and having better metrics to measure academic success.”

Shukla emphasized the importance of awareness campaigns that target AI-created research along with maintaining “robust standards” in academic reporting and validations of authenticity.

The International Science Council stated that the publication of research papers drives university rankings and career progression. This “relentless pressure” to publish research at all costs has contributed to a rise in fraudulent data.

“Unless this changes, the entire research landscape may shift toward a less rigorous standard, hindering vital progress in fields such as medicine, technology, and climate science,” the International Science Council stated.

To make matters worse, Prywata said that when AI-faked data get published, the information can be used to train new AI models, creating a feedback loop of misinformation.

“We need consequences,” he said.

A student sits in a lecture hall as class ends at the University of Texas at Austin on Feb. 22, 2024. Emphasis on publishing volume in academia has long been tied to job security and funding, but Michal Prywata says that the incentive system must change, with researchers and institutions held financially liable for fabricated work. (Brandon Bell/Getty Images)

Currently, there’s little in the way of incentives not to publish as much academic material as possible. The volume of published content at the university level has long been associated with job security and access to project funding.

“The solution isn’t better [AI] detection tools; that’s an arms race that will be lost,” Prywata said. “There are already tools being built to beat AI detection.”

He said he believes that the incentive structure for academic publishing needs to change entirely, making researchers and institutions financially liable for releasing fabricated work.

“Stop rewarding publication volume and fund based on citation quality and real impact,” he said.

Wenzler said that although peer review is still the “gold standard” for validating research findings in journals, it’s critical for the groups who conduct the reviews to invest the necessary time and technology.

“Put the research through its paces and validate any sources given,” he said.

Wenzler said he believes that a broader base of cooperation among academic institutions and government investment is needed to support research integrity.

Unfortunately, the peer review system is not without its challenges. Plagued by a growing stream of content and time constraints, reviewer fatigue is a common problem. Compounding this, evidence suggests that AI is playing a greater role in the peer review process, prompting a new wave of concern from the scientific community, according to a March article in Nature.

“Require live peer review with public reviewer identities,” Prywata said. “Also, fund peer review properly instead of expecting free labor.”

Correction: A previous version of this article misstated the research paper that concluded that LLM tools can generate plausible research that passes standard plagiarism checks. The Epoch Times regrets the error.