Epoch Times CEO Janice Trey’s thirst for truth sprouted from an unlikely place: a Chinese labor camp.

She was born in the middle of the Cultural Revolution—one of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leader Mao Zedong’s campaigns that targeted traditional Chinese culture, killing an estimated millions.

Authorities had labeled people like her parents, college-educated engineers, as an inferior class and sent them to a labor camp in a remote southern Chinese village. There, Trey spent her first nine years, growing sugar cane, carrying fertilizers to the top of the hill, and picking crops during harvest season. Her parents farmed and sewed. To go to school, Trey walked 1 1/2 hours every day to another village, passing hills, cemeteries, and snakes, she told PragerU CEO Marissa Streit on her “Real Talk” podcast.

She never saw fridges and cars in the camp, things that she read about in pamphlets that flew across the sea on balloons from Taiwan, mainland China’s democratic island neighbor. She had wondered if they were true.

Living her first nine years in the camp and then making it out of China gives Trey an inside view of two vastly different worlds and ingrained in her a commitment to seek—and spread—true information, a task she’s spearheading at The Epoch Times.

“Freedom and totalitarian regimes are opposites,” Trey said during the show aired on Nov. 13. And to have true freedoms, she said, keeping people informed is necessary.

When Trey’s family escaped the mainland to Hong Kong, she immediately felt a “breath of fresh air,” she said. No longer was she forced to sing songs praising the CCP or study propaganda-filled books. She got her hands on textbooks in the same period from various places—Hong Kong, Taiwan, and mainland China—and noted how different they looked.

Any remaining illusions she had about the Chinese regime shattered about a decade later, when Beijing opened fire on unarmed students protesting for political reform in Tiananmen Square.

Chinese authorities denied any bloodshed. But Trey knew better. Her best friend, a medical student, was at Tiananmen Square on June 4, 1989, ferrying loads of bodies to the hospital in the hope they could survive.

Trey, reflecting back at the 70-some years of communist rule, noticed a pattern.

“If you look back in the communist history, every decade an innocent group of people were chosen, and so that the rest of the people live under self-censorship, and that’s how the Communist Party’s trying to suppress any opposition,” she said. Exactly 10 years after the Tiananmen Massacre, Beijing began to target another segment of society that numbered in the tens of millions: the meditation group Falun Gong, a faith that emphasizes the values of truthfulness, compassion, and tolerance.

Red Guard members wave copies of Chairman Mao’s “Little Red Book” at a parade in Beijing during the Cultural Revolution in June 1966. (Jean Vincent/AFP via Getty Images)

There’s a reason why the atheist CCP goes after tradition and spirituality, she said.

For over 5,000 years, China didn’t have communism, and “communist party leaders were very afraid of the revival of the traditional values,” Trey said. “That’s why they burn books, they destroy statues, and they even change the Chinese characters.”

As one example, she pointed to the Chinese character for “progress.” The traditional version of the word consists of two words collectively meaning getting into a better place, but after Chinese authorities simplified it, the characters now describe getting into a well—a dead end. In a similar fashion, she noted, the simplified character for “love” lost the “heart.”

This systematic destruction of traditional heritage is why The Epoch Times made it its mission to bring “truth, tradition, and hope,” Trey said.

The Epoch Times’ founders experienced firsthand the human rights situation in China. Many had fled after years of harrowing persecution, an experience that instilled in them “an unwavering commitment to integrity, truthfulness in reporting, and respect for human rights and freedom,” the publication states on its About Us page.

Beginning in a basement in Atlanta in 2000, The Epoch Times set out with an aim to deliver uncensored news from China. Over the years, it has grown into an international newspaper with 22 languages in 36 countries and regions. When SARS broke out in China in 2003, the newspaper was weeks ahead in reporting the issue before Beijing acknowledged the virus—a pattern of cover-up that continues almost two decades later, allowing another deadly virus to spread around the world.

The reporting had helped alert some readers to health risks they were otherwise unaware of, Trey said. Readers have written thank you notes saying they canceled their flights to China after reading Epoch Times articles, she said.

“The media is also playing a role in saving lives,” she said.

In 2004, The Epoch Times published the Nine Commentaries of the Chinese Communist Party to unpack the true nature of the CCP, inspiring a grassroots movement among Chinese citizens to cut their ties with CCP-affiliated organizations. The paper was also the first to report on the practice of forced organ harvesting in 2006, exposing the lucrative state-sanctioned scheme to kill imprisoned Falun Gong practitioners for their organs.

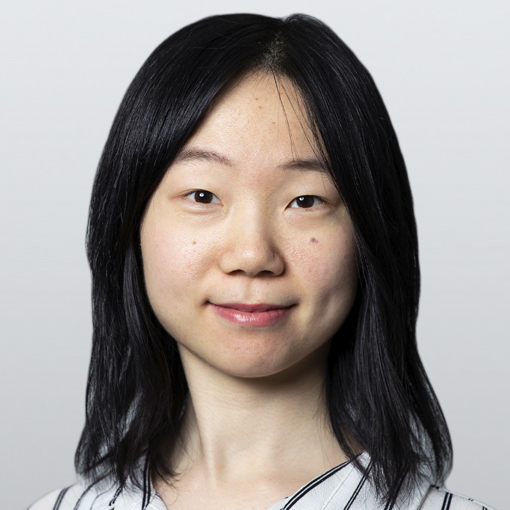

Epoch Times CEO Janice Trey speaks during an interview with PragerU's Real Talk, released on Nov. 13, 2024. (Screenshot via The Epoch Times)

Since its inception, The Epoch Times has been on Beijing’s blacklist. In late 2000, Chinese authorities arrested over 30 Chinese who reported, edited, or contributed to The Epoch Times from within China in various capacities. Several of them were sentenced to up to a decade in prison.

The printing press for the newspaper’s Hong Kong bureau, which suspended operations in September, had repeatedly suffered break-ins and other sabotage, including an arson attack in late 2019. Suspicious men stalked, and then assaulted an Epoch Times reporter in Hong Kong with an aluminum bat. The Epoch Times’ website is frequently met with cyberattacks linked to China, and reporters in the United States along with businesses that run advertisements in the publication have received threats.

“We are the only media that the Chinese Communist Party’s most afraid of,” said Trey. Despite the Chinese regime’s continued internet blockade barring The Epoch Times from being accessed inside China, people there have been using special tools such as VPNs to access its content, she noted, “because they knew we were telling the truth.”

The Epoch Times puts a strong focus on highlighting the ongoing human rights abuses of numerous groups in China, including the 25-year-long persecution of Falun Gong.

“Small candles can light up the whole room,” said Trey. After the Holocaust, “when we think about ‘never again,’ it is happening with the persecution of Falun Gong, and there are too many bystanders who have not spoken up.”

Having survived one mass communist campaign and having witnessed two more in action, Trey said she appreciates a chance to make a difference at The Epoch Times—to “give a voice to the voiceless.”