The Supreme Court held high-stakes arguments on Nov. 5 over the legality of President Donald Trump’s global tariffs.

For nearly three hours, the justices probed whether Trump’s reciprocal and fentanyl tariffs were authorized by a 1970s emergency powers law.

Multiple federal courts have held that Trump’s tariffs exceeded what Congress authorized him to do under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA).

In Article I, the Constitution grants Congress the power to impose tariffs. The government argued, however, that Congress allowed Trump to exercise that power through the IEEPA, which allows presidents to regulate imports, among other things, in response to emergencies.

It’s difficult to predict how the justices will rule. Some justices seemed mostly skeptical of the tariffs, but others were more difficult to read. Their questions explored whether tariffs are taxes, how much courts should defer to Trump’s discretion, and whether the administration is reading too much into the law.

Here are some of the main issues in the case and how the justices discussed them.

1. Defining Imports, Tariffs, and Licensing

The Supreme Court’s decision could hinge on how it interprets words in the law, such as “imports,” “regulate,” and tariffs.

Although the law allows presidents to regulate imports, Chief Justice John Roberts and lower court judges have noted that it doesn’t use the word “tariff” in the relevant section.

The law states in part that the “the President may, under such regulations as he may prescribe, by means of instructions, licenses, or otherwise … investigate, block during the pendency of an investigation, regulate, direct and compel, nullify, void, prevent or prohibit, any acquisition, holding, withholding, use, transfer, withdrawal, transportation, importation or exportation of, or dealing in, or exercising any right, power, or privilege with respect to, or transactions involving, any property in which any foreign country or a national thereof has any interest by any person, or with respect to any property, subject to the jurisdiction of the United States.”

U.S. Solicitor General D. John Sauer pointed to the long list of verbs in the law as an indication that Congress wanted the president to have a broad set of powers.

D. John Sauer, U.S. solicitor general nominee, testifies during his confirmation hearing in Washington on Feb. 26, 2025. (Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

“The natural common sense inference from that grammatical structure is the intention of Congress to sort of cover the waterfront,” he said.

At one point, Justice Amy Coney Barrett suggested that her decision could turn on another phrase—“licenses”—which she indicated could be viewed as similar to tariffs.

Justice Neil Gorsuch similarly suggested that licenses are “economically identical” to tariffs and that the word “otherwise” could allow the president to use tools such as tariffs. He also seemed open to viewing the term “regulate” to allow tariffs.

“Regulate is a capacious verb, and then you’ve got the ‘otherwise’ language as well,” he said.

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson was more critical, telling Sauer that Congress used the law to constrain presidents rather than grant them “unlimited” authority.

2. ‘Donut Hole’

During oral argument, Justice Brett Kavanaugh took issue with the argument of Oregon Solicitor General Benjamin Gutman, representing a dozen states challenging the tariffs, that the IEEPA gives the president authority to shut down foreign trade altogether but not to levy tariffs.

Kavanaugh said that Gutman’s take on the law “would allow the president to shut down all trade with every other country in the world or to impose some significant quota on imports from every other country in the world, but would not allow a 1 percent tariff.”

This would be an “odd donut hole” for Congress to leave in a statute, the justice said.

Gutman, who favors a stricter interpretation of the language in the statute than the Trump administration, replied, “It’s not a donut hole—it’s a different kind of pastry.”

(Left) Supreme Court nominee Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson testifies during her confirmation hearing in Washington on March 22, 2022. (Right) Supreme Court nominee Judge Amy Coney Barrett testifies during her confirmation hearing in Washington on Oct. 13, 2020. (Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images, Kevin Dietsch/Pool/Getty Images)

The power to shut down trade is “fundamentally different” from the power to impose tariffs, the lawyer said.

Barrett told Gutman that it did seem to make sense for Congress to empower the president with “something that was less, weaker medicine than completely shutting down trade as leverage to try to get a foreign nation to do something.”

3. Are Tariffs Taxes?

Neal Katyal, who represented a group of businesses suing Trump, told the justices they shouldn’t view the tariffs as a way to regulate imports. Instead, Katyal and Justice Sonia Sotomayor argued they were taxes.

If the Supreme Court views Trump’s tariffs as taxes, that would also raise questions about whether Trump is encroaching on a power that the Constitution gave to Congress.

Sotomayor told Sauer she didn’t understand his argument that tariffs aren’t taxes.

“You want to say tariffs aren’t taxes, but that’s exactly what they are,” she said. “They’re generating money from American citizens, revenue.”

Kavanaugh disagreed.

Since the early days of the republic, the Supreme Court has “repeatedly” said that a tariff applied to foreign imports is an exercise of the commerce power, not of the taxation power, Kavanaugh said.

This seems “to at least undermine a bit” the point that it’s an entirely different power, he said.

Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor speaks in the Great Hall of the Supreme Court in Washington on Dec. 18, 2023. (Jacquelyn Martin/Pool/Getty Images)

4. Can Congress Delegate Its Tariff Authority?

Even if the court decides that the IEEPA allows tariffs, the court could still reject Trump’s tariffs on the basis that the law violates the nation’s separation of powers.

A legal doctrine known as the “non-delegation doctrine” generally prohibits Congress from delegating its legislative powers to other entities, but it contains some caveats.

Another doctrine that came up during oral argument was the “major questions doctrine,” which says that administrative agencies need clear congressional authorization before making decisions of major economic or political importance.

Sauer told the justices that the major questions doctrine shouldn’t be applied to Trump’s tariffs because they were part of foreign affairs, which is an area in which presidents generally have more authority.

Gorsuch seemed concerned that the administration was presenting a legal theory that would lead to an overly expansive view of executive authority.

“What would prohibit Congress from just abdicating all responsibility to regulate foreign commerce, for that matter, declare war to the president?” the justice asked Sauer.

Justice Elena Kagan was similarly skeptical. She told Sauer that if Congress wanted to delegate its power, it had to provide some kind of meaningful limit.

“How does your argument fit with the idea that a tax with no ceiling, a tax that can be anything, that here the president wants ... would raise a pretty deep delegation problem?” she said.

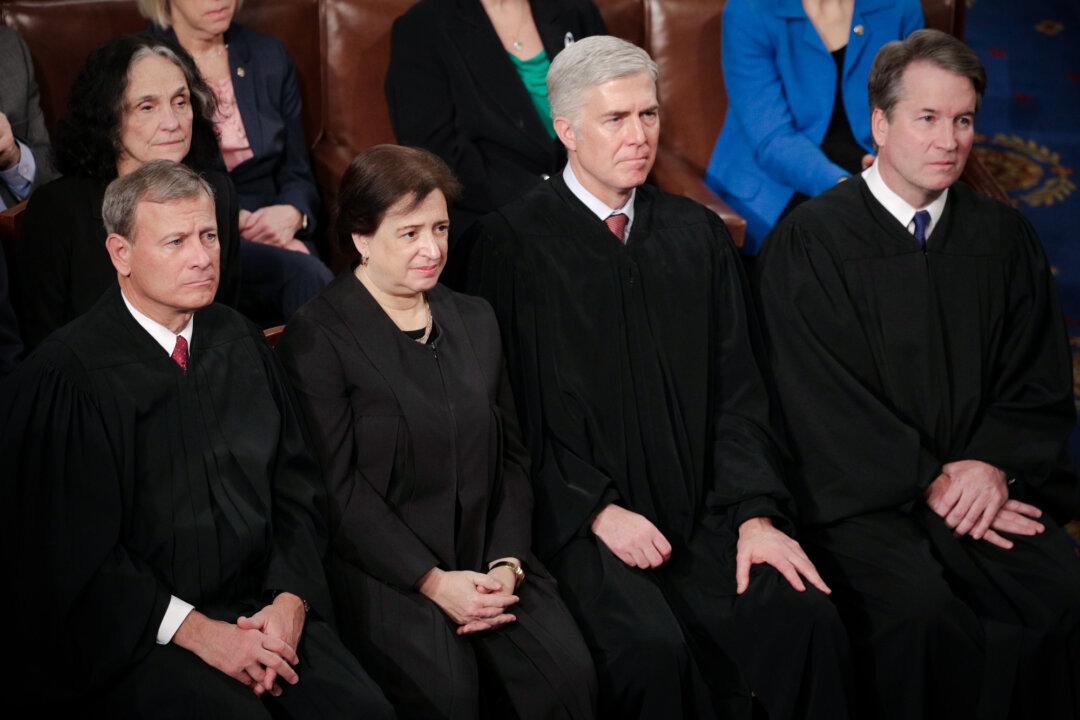

(L–R) Supreme Court Justices John Roberts, Elena Kagan, Neil Gorsuch, and Brett Kavanaugh look on as President Donald Trump delivers the State of the Union address at the U.S. Capitol on Feb. 5, 2019. (Alex Wong/Getty Images)

5. Concerns Congress Can’t Take Back Authority

Gorsuch expressed concern that once Congress delegates its tariff authority to the president, it may not be able to take it back by passing a new law.

“Don’t we have a serious retrieval problem here because, once Congress delegates by a bare majority—and, of course, every president will sign a law that gives him more authority—Congress can’t take that back without a super majority?” he said.

Gorsuch suggested that a future president is likely to veto an attempt by Congress to reclaim its power from the executive, meaning the new law would need to be veto-proof.

“What president’s ever going to give that power back?” he asked.

Sauer disagreed that Congress could “never” get that power back. He pointed to Congress’s termination of the COVID-19 emergency in 2023 as an instance in which Congress reined in the executive branch.

Vice President JD Vance and Speaker of the House Mike Johnson (R-La.) applaud as President Donald Trump addresses a joint session of Congress at the U.S. Capitol on March 4, 2025. The Trump administration has collected nearly $90 billion in revenue in fiscal year 2025 from the tariffs challenged in this case. (Andrew Harnik/Getty Images)

6. Refund Process

The justices discussed what would happen if the Supreme Court upholds the lower court rulings that struck down the tariffs.

Barrett said if the tariffs are invalidated, the reimbursement process “could be a mess.”

The Trump administration has collected nearly $90 billion in revenue in fiscal 2025 from the tariffs challenged in this case.

Justice Samuel Alito also discussed the complicated process should the court invalidate the tariffs, only for the Trump administration to impose new tariffs using different legal authorities, which would then likely be challenged and work through the court system again.

Alito posited that it might make more sense for the court to address whether section 338 of the Tariff Act may justify Trump’s tariffs so the court could “get it over with rather than having this continue for who knows how long while it goes … through the procedures in the lower courts.”

Katyal said the Trump administration had previously opposed suspending the collection of the tariffs while litigation continued in the lower courts, saying refunds could be issued. Later, the federal government said that having to refund the billions of dollars collected would be problematic, he said.

“I think it’s rich for the government to be making this argument about the refunds,” the lawyer said.

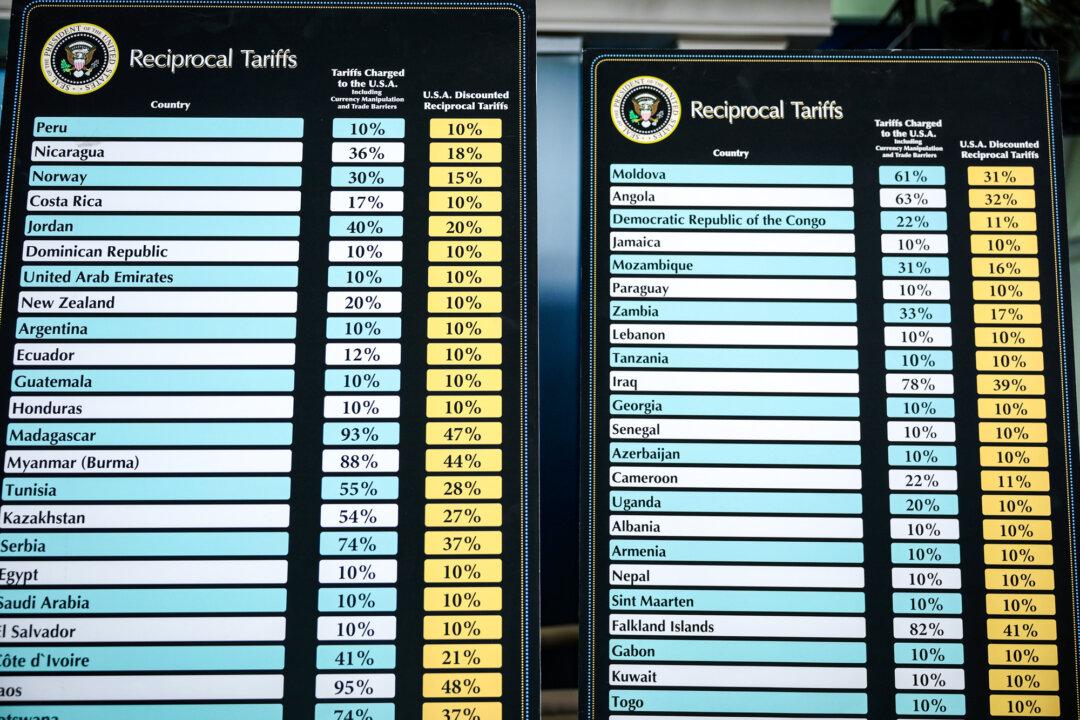

Charts that show the reciprocal tariffs that the United States is imposing on other countries are on display in the press briefing room of the White House on April 2, 2025. (Alex Wong/Getty Images)